‘Haunted me’: Why sibling abuse is the forgotten abuse

A new book is lifting the lid on a devastating hidden problem affecting countless families across the country and the world.

Real Life

Don't miss out on the headlines from Real Life. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Warning: Distressing details

If a man punches a woman in the face or throws a hammer at her head, it is regarded as a violent assault. If a sibling punches a sibling or throws a hammer at their head, it is regarded as sibling rivalry.

Sibling abuse is a spectre that has haunted me for much of my life. Until a few years ago, I did not realise that my late sister’s ongoing aggression towards me constituted “sibling abuse”. A psychologist pointed it out. Named it. I began to use this label, although I felt quite uncomfortable doing so. There is a societal expectation that we should get along with our brothers and sisters. Be friends for life.

Not only did I experience sibling abuse (physical assaults and psychological abuse) at the hands of my sister when we were children, but the abuse continued when I was a teenager and into my adult years. I wrote about this abuse in my new book, My Father’s Suitcase.

Since its publication, many people, including journalists, have said they were not aware that there is such a thing as sibling abuse. I’ve received comments such as: “I had never heard of sibling abuse before. I’m so sorry you had to suffer so much from it”; “My sister was abusive and I never conceived of the idea of sibling abuse until you put a name to it”.

When I began looking at the research in this field, I was surprised to learn that sibling abuse is by far the most common form of abuse in the context of family violence, and occurs four to five times as frequently as spousal or parental child abuse. It is significantly more prevalent (as much as three times) than school bullying. A study in the UK found that in a sample of 6838 children, 9.7 per cent reported being bullied, with the onset of bullying typically occurring around eight years old.

The 2016 Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence reported that sibling violence is a common form of family violence, with “the highest levels of violence of any family relationship”. It noted that this form of family violence often receives inadequate recognition.

One victim told the commission: “Sibling violence often flies under the radar and I believe it is too often put down to kids just being kids, but violence is violence and the effects, regardless of who is inflicting it, are the same. As [a] child victim of persistent sibling violence coupled with inappropriate responses to it from the adults around me, I feel that my own life has been impacted”.

Dr Michael Salter, Professor of Criminology at the School of Social Sciences at UNSW and an expert in child sexual exploitation and gendered violence, told me, “We don’t talk enough about the complexity and ambivalence of sibling relationships ‒ or just how violent siblings can be towards each other. A neglected form of family violence”.

Sibling violence tends to be overlooked in large part because families and the wider society regard it as a normal part of sibling relationships. It is often dismissed as sibling rivalry.

They are different. Sibling rivalry is competitiveness and jealousy between siblings ‒ squabbling, teasing, playing rough and the unwillingness to share things.

In contrast, sibling abuse is the ongoing and repeated use of violence by one sibling against the other. Like any other abuse, sibling abuse can be physical (kicking, slapping, biting), psychological (derogatory taunting, manipulating, teasing, name-calling) or sexual (the most common of intra-familial sexual abuse).

Sibling abuse occurs mostly in a dysfunctional family, where parents have not learnt to process their own trauma. There may be spousal violence and parental child abuse, including neglect, already occurring.

In her study on adolescent family violence in Australia, Professor Kate Fitz-Gibbon found that, “Young people who had used violence against a family member in their lifetime had witnessed family domestic violence or been targeted by child abuse”.

She concluded that there was consistent and strong evidence of intergenerational transmission of violence in the home.

According to Dr Rachael Sharman, a lecturer in child psychology at the University of the Sunshine Coast, some parenting styles enable and facilitate sibling abuse. For example, narcissistic parenting, Dr Sharman says, is “where a ‘golden child’ is showered with love and attention and can do no wrong while another child is deliberately cast into the role of the family scapegoat and can do no right”.

I was the older child and was told that my job was to look after my sister, look out for her.

Hence my parents would blame me for my sister’s attacks: “What did you do to upset her?”

If my mother found me crying, instead of comforting me, she’d say that I was too emotional.

I think mum was negligent and irresponsible to not feel sympathy for me. Perhaps she thought it was normal behaviour?

In her study of family violence, Prof Fitz-Gibbon found that sibling violence among adolescents is often dismissed as “normal sibling behaviour or minimised within families due to feelings of shame and guilt”.

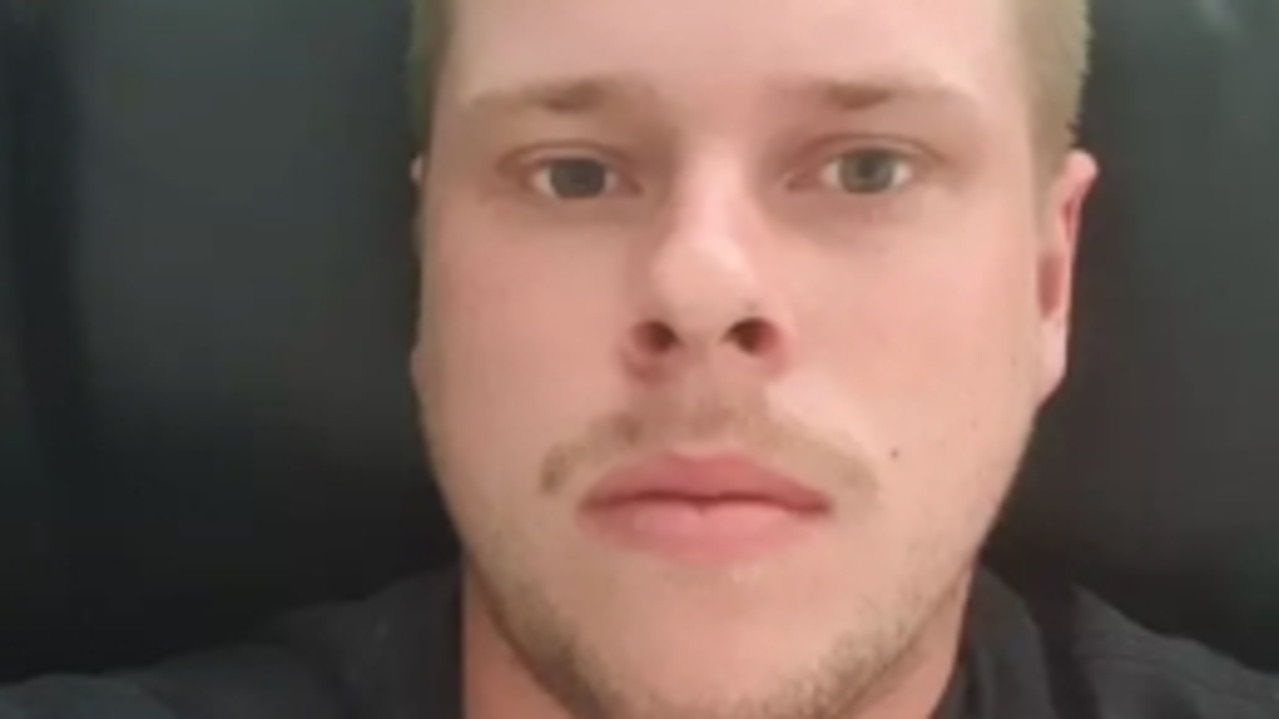

After reading my book, John* messaged me. He was on holiday in Thailand. He said he is not a big reader, but couldn’t do anything the first two days but read my book. It made him reflect on his own experiences of sibling abuse. He says the abuse only lasted for five or six years, but it clearly had an impact on him that he needs to better understand.

A 45-year-old father of two young children, John said that when he was around five years old, he would go and stay with his father and his new partner, who had three children from her previous marriage.

“I never felt safe, just felt like the weak little pathetic boy. They’d all overtly say that, make fun of me. One of the boys forced me to smoke cigarettes, would play extremely rough games with me, basically beating me up. It escalated at one point to rolling me down stairs, he even tied me up in chains. It all felt right and normal, as it felt part of the Australian culture, to be tough and stuff,” he said.

John later admitted: “I just had a big cry after writing this. I haven’t cried much, only once or twice like that in my whole life. Clearly there’s more there I need to process; I had no idea”.

There are far-reaching adverse effects of sibling abuse.

“Long term, sibling bullying can damage relationships between the siblings as well as family members who may take sides, or deny the problem to preserve family harmony. Sibling bullying has been found to double the risk of the victim experiencing depression and self-harm in adulthood,” Dr Sharman says.

What should be of concern to those working in the family violence sector is the role sibling abuse can play in the cyclical process of violence.

American author and family therapist Darlene Lancer explains that intimate relationships in adulthood can mirror the dynamics in sibling relationships, a pattern known as the repetition compulsion. If the victim is socialised to the use of violence ‒ they have learnt to tolerate or accept it ‒ they may find themselves in similar situations as adults and unknowingly repeat the cycle of violence.

“They can develop co-dependent and pleasing behaviours, repeating their accommodating, submissive, victim role”, Lancer says.

This happened to me. During the 1990s, I had several relationships with men who were violent ‒ physical, sexual, psychological violence ‒ and I was retraumatised with the subsequent court processes in order to obtain protection orders.

“It is all your fault,” men would tell me. “You’re crazy and overemotional.” I believed them, just as I had believed my parents when they would blame me for my sister’s attacks.

Fortunately, I got help, embarked on long-term therapy and began to heal the pain of my childhood and rid myself of the shame that had built up over the years. Writing, also, helped me understand the past and make sense of things. I hope my book will help others who have suffered at the hands of a sibling feel less alone and that it will encourage people to talk about this important issue.

*Name has been changed

Mary Garden is a freelance journalist and award-winning author with a PhD in journalism

Originally published as ‘Haunted me’: Why sibling abuse is the forgotten abuse