Sir Llew: 'I tried to make a difference'

Having stepped aside from public life, former state Liberal leader Sir Llewellyn Edwards now finds pleasure in art, books and being a good husband.

CM iPad section Front Page

Don't miss out on the headlines from CM iPad section Front Page. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Having stepped aside from public life, former state Liberal leader Sir Llewellyn Edwards now finds pleasure in art, books and being a good husband.

Queensland's former deputy premier and head of Expo '88, Sir Llewellyn Edwards, commonly known as Sir Llew, is having one of those days. He has just turned 76 and has retired from everything except his unofficial duties as his "darling'' wife's driver and his new job of being his own man.

"I decided some years ago that by the time I was 75 I would have one board only, and that was the board of Llew and Jane,'' he says.

He's running late for our meeting at the couple's beautiful 150-year-old Queenslander, "Corinth'', in Ascot, a dress-circle inner northern suburb of Brisbane. He's rushing, and apologising, and offering to make tea and generally exhibiting all the qualities of gentlemanliness and good manners that made him one of the best-regarded politicians of his generation.

"Please, call me Llew,'' he says.

Llew was one of the few Queensland ministers from the rotten ranks of the Bjelke-Petersen regime to emerge relatively unscathed from the Fitzgerald Inquiry, that blast of salts that moved through Queensland in the 1980s, cleaning out corrupt police and politicians. He went on to become a member of various boards, as well as chancellor of the University of Queensland for 16 years until his retirement in 2009. UQ Vice-Chancellor Professor Paul Greenfield said at the time that "no accolades could do justice to [Edwards'] contributions''.

"Without taking a day's pay in almost 16 years as chancellor, he has built enormous goodwill not only for UQ but also for Australian higher education at home and internationally.''

This morning, in his generously proportioned living room adorned with the work of Aboriginal, French and American artists ("We don't buy them for investment but because we love them''), Edwards is happy to talk about his life. But first he gives me a tour of the house he knew in the '60s as a medical student attending the tutorials of Dr Ken Jamieson, who then owned it. "Amazing coincidence, isn't it?'' he says.

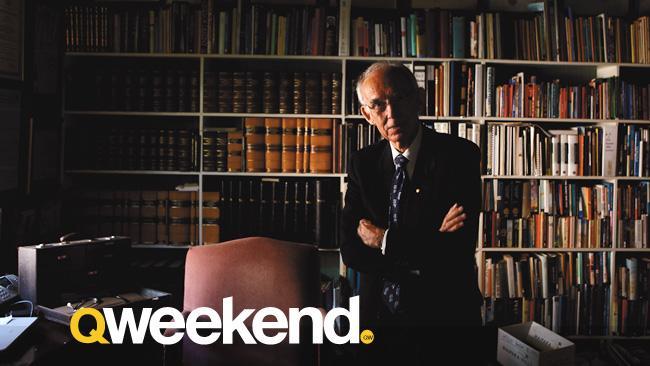

The library is lined with bookshelves stacked with pigskin-bound parliamentary Hansards and papers he tabled in his 12 years in parliament as health minister, treasurer and deputy premier. Edwards was the Liberal member for Ipswich from 1972 to 1983 and Liberal Party leader from 1978 till 1983, until he was challenged by former pharmacist Terry White.

In Edwards' impressive library there are also vehicle number plates from Expo on the walls ("worth a fortune, but we'd never sell them''), a framed Order of Australia citation, and his knighthood from the Queen. "Please don't think I'm boasting,'' says Edwards when I stop to look.

There are dozens of framed newspaper cartoons. In one, a younger, bushier-browed Llew is attired as a blushing bride "marrying'' Joh. The library is only a small part of Edwards' archive - the rest of his papers have been donated to the University of Queensland, which is cataloguing them. In honour of his contribution to UQ, it has renamed the GPN4 building as the Sir Llew Edwards building.

Back in his loungeroom, with cups of tea, Edwards' short-term memory is not a patch on his recall of past events. He remembers as if it were yesterday the former Liberal Party leader (and premier for a week) Sir Gordon Chalk striding into his Ipswich medical practice one day in 1972.

"My secretary came in and said, 'There's a very rude man in the waiting room wanting to see you and he hasn't got an appointment'. Well, in those days, appearing to see a doctor without an appointment was just about an eternal sin. We had this little peeper screen so we could look out and see how many patients were left, so I looked out and said, 'Goodness me, that's Sir Gordon Chalk!'

``So I found my old coat that I kept there if I got cold, more than anything, took off my white coat and they brought him into the room. When he came in I said, 'I'm Llew Edwards', and he said, 'I know who you are! What do you think I'm here for?'?''

Chalk was there to talk Edwards into running for Ipswich. Edwards' first instinct was to say no thanks, that he was happy practising medicine (Edwards pronounces it the old-fashioned way, as ``medcin''). Chalk told him to sleep on it and, as luck would have it, Edwards was on call that night and was out of bed five times, delivering babies and rushing about here and there, and as the sun came up as he was driving home, he thought: Anything would be better than this. He stood and won the seat.

Like many Queensland politicians back then, Chalk was the tough-talking kind. "He was a very brash man, for whom I developed an enormous fondness,'' says Edwards.

Another tough-talker, about whom Edwards has mixed feelings, was the gruff and grossly obese "Minister for Everything'', Russ ("Never hold an inquiry unless you know what the outcome will be'') Hinze, who died in 1991 before he could face trial on bribery charges stemming from the Fitzgerald Inquiry.

Edwards remembers Hinze on the day of Joh Bjelke-Petersen's infamous hydrogen car fiasco in 1980, when the premier ordered his cabinet down to Brisbane's City Plaza "to see history in the making'' (an inventor named Stephen Horvath had impressed the premier with his ideas for a hydrogen-powered vehicle). As the assembled media waited for the miraculous display of this world first, the keys to start the car went missing. "Hinze went over and said, 'If you don't find that key in five minutes I will break your neck', and the rest of us just sort of stood around, waiting,'' Edwards recounts, laughing.

He has mixed feelings, too, about his late boss: "I had a lot of admiration for Joh on a day-to-day basis I thought he was a simple, hardworking, good premier when I became minister for health.''

But his disagreements with Bjelke-Petersen began with the premier's opposition to then prime minister Gough Whitlam's introduction of Medibank in 1975, which Edwards supported. Clashes continued when Bjelke-Petersen asked Edwards to register fraudulent medico "Dr'' Milan Brych.

Perhaps surprisingly, Edwards is not an uncritical supporter of the Fitzgerald Inquiry. He endured the scrutiny of every bank account he had held for the previous 20 years, and believes now that the consequences of such inquiries have included over-regulation and unnecessary bureaucratic processes that cost governments too much.

"I think Fitzgerald did some good, but it could have been done without a massive commission of inquiry,'' he says. ``Of course, accountability in public life is essential, absolutely essential, but now, no minister can spend anything without going through 90 [processes], and we've got delays everywhere.''

If Edwards' memoirs would make fascinating reading, he's not interested in writing them. His trajectory from electrician to doctor to politician is an unusual one. There can't be many doctors who are also electricians (Edwards' father, Roy Edwards, founded the Ipswich electrical firm RT Edwards and firmly believed that his sons should have a trade, regardless of whether they wanted to become doctors. "Dad said: 'You'd be better off with a trade, you'll make a better doctor even', and that was that'').

He believes there are two or three writers working on his biography, but all are unauthorised. "I'm not being uncooperative. I'm correcting things when they come to me with a few questions, but I've made it very clear it will have to be unauthorised. You might find that a bit strange Jane does a bit, too but my view is that, look, even if these books are written, in 30 years' time people are going to be saying, 'Who?'?''

These days he takes his greatest pride in being a good husband to Jane, now Lady Edwards but once plain Jane Brumfield. His second wife, and some 20 years younger than her husband, Brumfield married Edwards in 1989, after the death from asthma of his first wife, Leone, the previous year. Brumfield had been engaged to do PR for Expo. Today she runs BBS Public Relations and is Queensland's Honorary Consul for France.

Edwards drives Jane to and from work, drops her off for hair appointments and meetings, and they always make a point of just sitting down and chatting for an hour or so before they get dinner. "We've always done it to have that lovely, lovely friendship and confidence in each other is just wonderful. Now, I look after Jane better, I walk the dogs every day, I walk myself every day for an hour.'' He reads for at least an hour a day, too. He only had time to read newspapers while he was working. Now he reads historical books, Australian history and medical history mostly.

What does he consider his greatest legacy?

``I would hope that the three greatest legacies I've left are that the people of Queensland thought I was a friendly, honest person who tried to make a difference; secondly, the opportunity to build the best exposition in Queensland's history, which created so much fun and happiness and satisfaction and the promotion of Australia, particularly Queensland, was something I feel very, very proud about.

"And I've got one other thing. I think the years as chancellor, meeting and shaking hands with, they tell me, 88,000 graduates, seeing the dreams in their eyes as it were, seeing the expectation that they were going to have

a better life because of their education, often at great sacrifice to their parents, I think that's my third greatest thrill.''

And with that, Sir Llew stands up and insists on walking me out of the house, down the stairs and onto the street, right to the door of my car.