‘Who do you need to forgive?’ Scott Morrison’s confronting question

Former Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison reveals all in his new book – from his crippling anxiety to his political foes and what happened at home the night he lost the election.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In this first exclusive edited extract from his new book, former Prime Minister Scott Morrison shares insights into his personal and political highs and lows, his Christian faith – and how he navigated a global coup and a diplomatic incident.

SOME DAYS YOU WIN, SOME YOU LOSE

I cleared most of the people out of my study who had joined me at the prime minister’s official residence at Kirribilli House overlooking Sydney Harbour. It was election night in Australia: Saturday, May 21, 2022.

While the opposition had not yet won the necessary seats in Parliament to form a government, I had been through enough elections to know where things were heading.

There were practical things I now needed to arrange, so I asked my most senior staff to stay while everyone else joined our other guests in the sitting room.

I was disappointed with the looming outcome of this election.

I had worked hard and campaigned well. I had trusted God and put everything I had into the job. It was over. It was a hard loss. We had been soundly defeated. We had all sat in this same room three years earlier when we realised we had won an extraordinary and unlikely victory. A miracle victory, I called it. That’s politics: some days you win, some days you lose.

Over the next few days I would formally tender my resignation as prime minister to the governor-general.

After three terms, and almost nine years, the government of one of the world’s oldest and most prosperous democracies would peacefully change hands once again. On the other side of the world, in Ukraine, a much younger democracy was fighting for its survival against an illegal Russian invasion. Perspective is important at times like this.

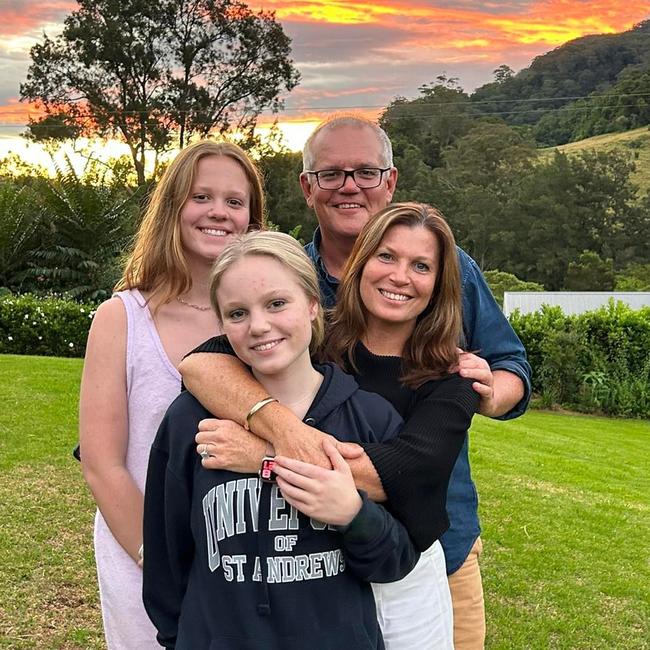

After speaking with my wife, Jen, I went upstairs to tell our daughters, Abbey and Lily. They had come to live at the prime minister’s residence from our home in the Shire as little girls and would now be leaving as teenagers. On nights like this they often liked to keep to themselves. As sisters they had been through a unique experience together. The house was full. Our family, friends, and staff had gathered, so the girls had retreated to the privacy and quiet of Abbey’s bedroom upstairs. They were sitting together on Abbey’s bed. I sat down on the other end and just looked at them for a moment. These were my miracle girls, God’s great gift to me and Jen. I was looking into the faces of God’s goodness. Life’s most bitter disappointments don’t stand a chance when you’re confronted with the truth of God’s blessings in your life. It was just what I needed.

I told them, “Girls, Dad has lost the election, and I won’t be prime minister anymore … we’re going home.” They knew I was disappointed. They both cried, not because we had lost but just because they loved their dad and didn’t like to see me disappointed. That night, they gave me a hug that only daughters know how to give their dad.

Despite the genuine disappointment of losing, I also felt a strange calm. Leading our country had been a great privilege, and I wanted to continue to serve. However, leading my country through a global pandemic, natural disasters, constant security threats, and recession in a malevolent and often toxic political environment had taken a heavy toll. After almost four years in the top job, nine years in cabinet, and having just completed a second national election campaign, I was exhausted, physically and emotionally.

DIGNITY IN DEFEAT

I had come to terms with our defeat. I respected the judgement of the Australian people. All things come to an end. I was not angry at God. Why should I be? He was still with me. His blessing is not found in the achievement; it is found in His presence.

However, I was not prepared for what happened next. I had expected the political caravan to move on and that my family and I would now be able to catch our breath and also move on, with dignity and respect. That didn’t happen.

After I lost the election, my opponents were not content to leave it there. In Australian politics we call this a “pile on”. Not satisfied with my defeat, they engaged in a campaign to humiliate, discredit, and cancel me. It was graceless, brutal, and it hurt.

When you’re in the job, you are so busy dealing with the numerous issues you must contend with that there is often little time to truly absorb the personal attacks that come your way. You develop a thick skin. In these days of social media, the attacks are far more sophisticated and effective. They create a cycle of hate that distorts reality. I never really recognised how vicious the attacks on me were until after I left office. Once the music stops, the attacks can be all you see and hear, even when you try to ignore them. As Christians we know what principalities and powers are often behind these attacks (Ephesians 6:12).

I decided not to take the bait, as I believed it would have only made matters worse. I turned down interviews and turned the other cheek. I knew that what was being said did not represent the truth of who I was, what I was about, and what we had been able to achieve. Wherever I went, people continued to approach me to say thank you for what we had done for them during the pandemic and my time as prime minister. This was in stark contrast to the public narrative now being driven by my political opponents and some in the media.

I also believed that my response was how a former prime minister should behave. While my opponents wanted to keep kicking, I wanted to follow the dignified example of those who had left office quietly and moved on. I recall that during the pandemic our first female prime minister, Julia Gillard, was being baited by the media into being critical of me and my government. Perhaps they thought that because she was from the other side of politics she would take a swipe. She refused to be drawn. She showed a lot of class. I hope to follow her example.

BEST DECISION I EVER MADE

I first met Jen when I was just eleven years old. It was a Saturday night at Luna Park, a popular amusement park next to the famous Sydney Harbour Bridge in North Sydney. Jen admitted many years later that she had liked me even then but thought I was a bit overconfident (some things never change). So she thought she’d just play it cool, keep an eye on me, and see what happened. There was no rush; she was only twelve.

We spent years in the same churches, going on fellowship outings and attending the regular round of Christian youth camps. It wasn’t until an Easter camp in our final year of high school, sitting together on a Saturday night on the end of the jetty at Kiwi Ranch at Lake Munmorah, just north of Sydney, that we first held hands and started dating. I told the camp leader the next morning that Jen was the girl I wanted to marry. I was just sixteen.

Almost five years later, after we had both finished university, we got married at a little chapel in Oatley in southern Sydney. It was the best decision I have ever made, other than to follow Jesus.

We had intended to travel to North America, where I was going to study divinity at Regent College in Vancouver, but life took us on a different path. I got offered a good job in Sydney. Dad told me I now had responsibilities as a married man and had a duty to settle down and take the job (which he had engineered, by the way – my Father was pretty cunning). I followed my father’s advice and took the job, which began my ultimate pathway into politics. I have always wondered where that other path may have taken us. Perhaps the same place?

WIND BENEATH MY WINGS

About a month before the 2019 election, I was somewhat despondent. We were continuing to trail in the polls and time was running out. I was on my way to the Central Coast of New South Wales just north of Sydney for a campaign rally. Jen was with me. I had recently shared with my pastor friends in our chat group how I had been reaching for God but not really feeling His presence.

He seemed distant to me. I just wanted to know that He was with me in all of this. Of course I wanted to win, but what was more important to me was His presence, His peace, and His assurance. I knew I could not function without these.

Before arriving at an event, we would typically go to a holding location to give time for media and security to be in place at the venue. On this occasion we stopped off at the Ken Duncan Gallery. Ken is a famous Australian photographer known for his inspirational Australian landscape and wildlife portraits. Ken is also a strong Christian. His images are incredible acts of worship. I walked into the side room of the gallery on my own. I really needed a lift and was reaching out to God once more.

There I was confronted by the majestic image of an eagle in full flight, with the wind beneath its wings, that Ken had taken on an expedition to Finland. The detail in the photograph was extraordinary.

I stood there transfixed, stunned into silence by its majesty. The image was titled Soaring Majesty. Isaiah 40:31 rushed into my mind:

Yet those who wait for the Lord

Will gain new strength;

They will mount up with wings like eagles,

They will run and not get tired,

They will walk and not become weary.

I strongly sensed God’s presence right there in that room with me. He was reminding me where my strength would come from and that He was indeed with me, no matter what.

I bought the print and hung it in my study in the Kirribilli residence, where it remained for the next three years after we won the election. Each day I was there, I would look at it and be reminded of God’s presence and faithfulness.

***

Weeks later, I stood up with Jen, Abbey, and Lily in front of a cheering crowd at the Wentworth Hotel in Sydney after we had won on election night. I proclaimed, “I have always believed in miracles.” It was my way of acknowledging God and seeking to give Him the glory.

A week before voters went to the polls, one of my close parliamentary colleagues asked me what Christians should pray for to be written on the front pages of the national newspapers the day after the election. I replied, without even thinking, “ScoMo’s Miracle.”

In my office today I have a framed picture of the front page from one of Australia’s major city newspapers published the day after the election with that exact headline.

RUOK? FACING ANXIETY

In 2021, we put a new question in the official census of the Australian population. We asked Australians whether they identified as having a long-term health condition. Of the two in five Australians who said they did, the most prolific condition specified was mental illness.

Over two in five adult Australians had experienced a mental disorder at some time in their lives, and one in five had experienced a mental health disorder for at least a year.

Of those, anxiety was the most common group of mental disorders. That’s around 3.3 million people. There is a lot of hurt and anguish going on just below the surface in our communities. Young people are proving to be especially vulnerable.

So how are you feeling? According to the statistics, you may be struggling with anxiety even as you read this. If so, you’re not alone.

Anxiety is different than fear. When facing imminent danger, a flight response makes sense. I have a fear of heights. Such fears can be very much in the moment. Once the danger passes, so does the fear. The anxiety I’m talking about is not momentary. It lasts much longer, feels inescapable and can be overwhelming.

I had some experience with this as PM and sought help from my doctor in Canberra, who prescribed me with medication that I found very helpful. We are all human. My doctor was amazed I had lasted as long as I had before seeking help. Without this help, serious depression likely would have manifested. It wasn’t the difficulty of the pandemic or global challenges I faced in the job that had this impact on me. I would run hard at these challenges every day. In some ways, those challenges kept me sane. What impacted me was the combination of pure physical exhaustion with the unrelenting and callous brutality of politics and media attacks.

As a politician, I know this goes with the territory. That’s not a complaint or even an accusation. It’s just reality. Politicians are not made of stone, yet they’re often treated as though they are, including by each other.

Anxiety can be debilitating and agonising. It doesn’t matter if it’s rational or not, because how you feel is very real. You dread the future and can’t get out of bed. It can leave you feeling hopeless and incapable. It can shut you down mentally and physically. It robs you of your joy and can damage your relationships. I know this from personal experience.

From a clinical perspective, anxiety can also make you sick — headaches, nausea, diarrhoea, shortness of breath, and chest pains, just to name a few symptoms. Anxiety can also lead to depression, self-harm, panic attacks, substance abuse, and disrupted sleep patterns.

It can affect your appetite and lead to eating disorders. It can even lead to psychosis and other mental illnesses. It requires clinical treatment in its more acute form. Anxiety is not something we can casually dismiss. You can’t deal with it by telling yourself to, “take a teaspoon of cement and harden up.”

It is real, and it can be deadly.

AUKUS: PUTTING AUSTRALIA FIRST

Amidst increasing regional belligerence from China, in 2021 the Morrison government announced the AUKUS nuclear submarines partnership with the US and UK. But first that meant cancelling a flailing $90billion contract for conventional subs with France …

I rolled up to the large courtyard of the almost three-hundred-year-old Parisian presidential palace that had accommodated French presidents since Napoleon’s grandson in 1848. I was greeted warmly by President Emmanuel Macron, and we held a brief media conference before entering the palace. He walked me to the back patio where our table overlooked the palace’s immaculate gardens. Suffice it to say, I was impressed and quite overwhelmed. Once again, a boy from the beachside suburbs of Sydney was a long way from home. There we were in Paris, on a ridiculously pleasant summer evening, about to sit down to probably one of the finest meals I’d ever had. I assure you, my preference was to just relax and enjoy the evening. But that wasn’t on the agenda.

Up until then, my relationship with President Macron had been positive and friendly. He was smart and charming, and we shared a passionate interest in the Pacific Island nations. As a prime minister, though, you cannot allow the sentimentality of your relationships to take precedence over your national interest. We exchanged gifts and some friendly conversation, but I knew I would have to turn the subject to submarines. Even though AUKUS had not yet landed, I could not leave that dinner without making it clear we were reconsidering our position on Australia’s submarine project with France.

I made it clear that this was not about missed deadlines or the project difficulties we had experienced thus far in the partnership.

If we proceeded with the French submarines, I was confident those issues could be ironed out, but I also knew it would mean further delays and that it would not be until 2038 that we would see the first submarine. It was also not about any deficiency in the French design. The French submarines were still the right choice if we were looking for a conventionally powered submarine. That was just no longer what Australia needed, and I made this clear.

I also explained that there had been significant changes in the strategic environment in the Indo-Pacific.

We discussed these changes and their implications. I said this meant conventionally powered submarines would no longer do the job we needed them to do. We needed nuclear-powered submarines. I told the president we were going to have to look at other options.

President Macron naturally wanted to know what these other options were. I said I couldn’t discuss those with him at this stage. I explained that we had not made a final decision, which we had not. Emmanuel asked to send his senior defence people to Australia to sit down with ours to talk the issue through. I agreed but said we would have to do it quickly. Emmanuel said to me, “I don’t like to lose.”

I had expected that our discussion of the submarine contract would bring our evening to a quick end. Generously, this didn’t occur. Emmanuel was a gracious French host. We continued to chat for about another hour before he kindly gave me a tour of the palace, even showing me some original documents signed by Napoleon himself. Quite amazing. We said goodbye on the palace steps, and I went back to our hotel and debriefed my senior national security team.

The next day the French defence establishment went into overdrive, contacting every Australian official they could. It was clear that President Macron had sent a rocket into his government and was pressuring his defence officials to get the project fixed. These actions signalled that he knew the contract was under threat. The next morning I addressed the thirty-four OECD member country ambassadors and held a media conference in the OECD foyer. At the media conference I was predictably asked about the French submarine contract. I confirmed I had discussed the issue with President Macron and purposefully noted that contracts have “gates” in them for a reason. I noted we were still yet to pass through the critical gate that the French contractor, the Naval Group, which is owned by the French government, had missed the previous December.

After returning from Europe we continued working with the United States and the United Kingdom to finalise our agreement. I wrote to President Macron reinforcing the points I had made at our dinner discussion. The French sent Vice Admiral Bernard-Antoine Morio de L’Isle to Australia to sort things out. Our defence team met with him and set out our assessments and reasoning, as I had done in Paris. The admiral did not agree with our assessment of the strategic situation in the Indo-Pacific nor the implications it had for our submarine program. This highlighted the problem. France wanted their contract and would not see past their own commercial interests. We wanted the best submarines to protect our national security. Our goals no longer aligned.

I have always assumed the French government and President Macron thought I was bluffing and just trying to squeeze them on the deal. They probably never believed that we could have pulled off something like AUKUS. I was not bluffing. I never bluff. The French failed to appreciate just how seriously we were taking the threat to our security in the Indo-Pacific.

As each week dragged on, it became harder and harder to maintain security over the project. More and more people became aware across the US, UK, and Australian systems as we worked to finalise the AUKUS arrangement. We also knew we would have to give

France formal notification of our decision not to proceed. If the French were given enough opportunity, I knew they would knock AUKUS over. They would deploy their considerable diplomatic resources to kill the AUKUS deal to protect their contract. I needed to wait until I had a firm date for the announcement. You don’t jump off one lily pad unless you have another one to land on. I could not risk it all unravelling.

The day before the announcement, I sent a message to President Macron, letting him know I had been endeavouring to schedule a call with him for a few days. He was proving elusive. He came back to me personally with a time that would have been too late.

He asked in his text message, “Should I expect good or bad news for our joint submarines ambitions?” This was not a question from someone who was oblivious to our concerns or the mortality of his submarine contract. He had not been misled as was later claimed.

I suppose admitting that the French government had failed to take what we were saying seriously, or that there had been a complete failure of their intelligence services, would have been more embarrassing.

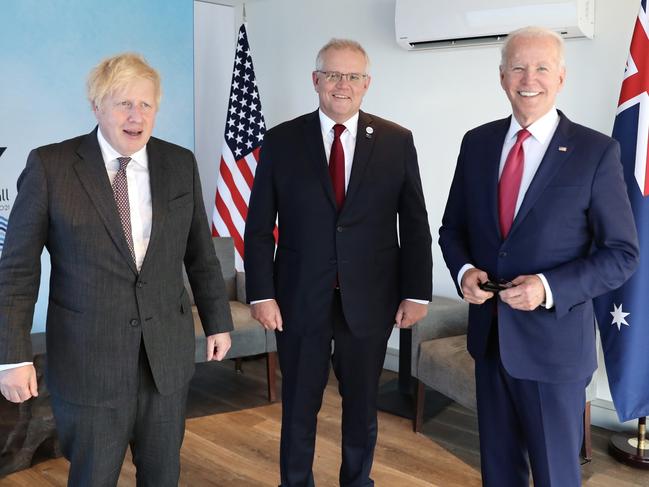

I replied saying we needed to speak that day. In the absence of any response, later that night in Canberra (by then morning in Paris) I sent a letter directly to President Macron via secure direct message advising him that we were ending our submarine contract and proceeding to acquire a nuclear submarine capability with the Americans and the British. The next morning, Australian time, I would be standing up with President Biden and Prime Minister Johnson to launch AUKUS. It was the longest night of my prime ministership. The French had almost twelve hours to topple the deal.

Thankfully, they were unable to do so. Our patience and preparations had paid off.

In response, France recalled its ambassador, the French president publicly called me a liar and called into question Australia’s capability to undertake the new project, and French diplomats did everything they could to sabotage the arrangement. I had read them correctly. There was also some discomfort from some of our Southeast Asian partners in Indonesia and Malaysia about the secrecy surrounding the arrangement and not having been consulted in advance. Of course they would have preferred to have known more about it before it was announced. Ideally, we would have liked this also. However, such an approach would have made AUKUS impossible to achieve. My critics said we could have also avoided offending France if we had given them formal notification earlier.

This was naive, as such notification would have only been used by France to disrupt the deal with the United States and the United Kingdom and make sure AUKUS never happened. There is no way to end a $90 billion contract where the other party walks away happy. But it had to be done.

I am pleased the new government in Australia is once again speaking with France and is also able to now engage more proactively with our neighbours in the region about AUKUS, but that is their luxury. Were it not for our courage to take the actions we did at the time and our preparation to suffer short-term discomfort and even personal reputation damage, AUKUS never would have happened. There is a reason Australia had not achieved anything on this scale for seventy years. Such achievements come at a cost, and those who wish to pioneer such advances must be prepared to accept that cost. I was.

FORGIVENESS OR VENGEANCE

After the shocking 2020 Oatlands car crash tragedy, when three of Danny and Leila Abdallah’s children and their cousin were killed by an intoxicated driver, the Morrisons forged a close bond with the Western Sydney family.

Forgiveness is a hard conversation. One night, about ten months after losing the election, I was having a beer with Danny at his place. He put a question to me squarely: “So, Scott,” he said, “who do you need to forgive?” It was a confronting question. And if anyone had the right to ask it, it was Danny.

Danny shared with me that night that when Samuel Davidson killed his children, he didn’t personally know the man. He said people make mistakes and do stupid, irresponsible, and reckless things. Danny and his family suffered terrible loss because of what Samuel did, but they didn’t know him. Amazingly, Danny is now getting to know Samuel in prison; they are talking about Jesus, even with Samuel’s family as well. Danny’s forgiveness was not just in the moment; it has been ongoing. Danny is now working on restoration and discipling Samuel. I knew I had to take up Danny’s challenge and example if I wanted to move forward.

Politics is a tough business. People clash. There is a lot at stake. People lose and people win.

In politics I saw a lot of vengeance and bitterness. People nurse grudges yet are usually blind to their own offenses, which mirror what they’re complaining about. For some, exacting vengeance becomes their sole purpose. It looked exhausting and, more importantly, pointless. I never understood where they found the time or what they hoped to gain, even when their vengeance was realised.

The road to becoming prime minister and then operating at the highest level of politics is not for the fainthearted. It is unrelenting.

Along the way you make mistakes and bitter enemies, you misjudge situations, and you certainly have your regrets. You can’t take the field in politics for as long as I have and emerge unscathed, without injury or without having dealt some of your own blows. Thankfully, for me, there were ultimately far more positive experiences, relationships, decisions, and outcomes that I was blessed to be part of. I am thankful for the opportunity to have served God and my country in such a privileged way.

Now that I am no longer prime minister, I have had the time to reflect over the many years I spent in the pressure cooker of politics. There are disappointments I have to let go of, where I must pay the price and forgive. There is also repentance I must come to terms with – things I have said, things I could have said better, people I have taken for granted or disappointed, and some policy decisions I regret. Now, I’m not going to turn this into a weeping public confessional; that is not my style. I’m not getting on anyone’s couch. Nor is this the point I am making. Those things are between me and God and probably a few others as well, where necessary.

My point is not that we should wallow in guilt or public flagellation. My point is about restoration and being able to move forward to the next season.

This is an edited extract from Plans for Your Good: A Prime Minister’s Testimony of God’s Faithfulness by Scott Morrison, which will be published by Thomas Nelson US/HarperCollins on May 1.

Originally published as ‘Who do you need to forgive?’ Scott Morrison’s confronting question

Read related topics:Scott Morrison