Hawke, Hazel and the truth about his beer-swilling university record

The true story of Bob Hawke’s beer-swilling record and his desperate appeal for distant fiancee Hazel to save him from temptation are among extraordinary accounts in a new book.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

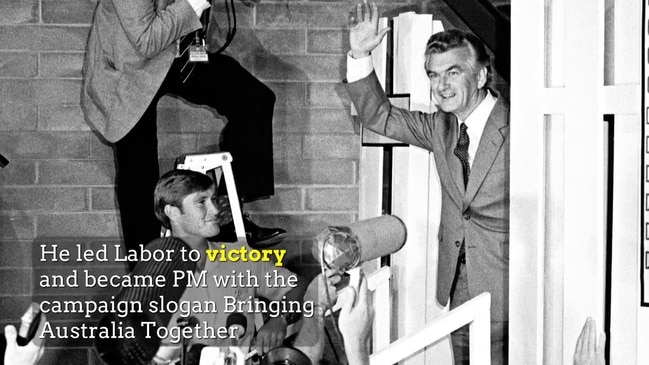

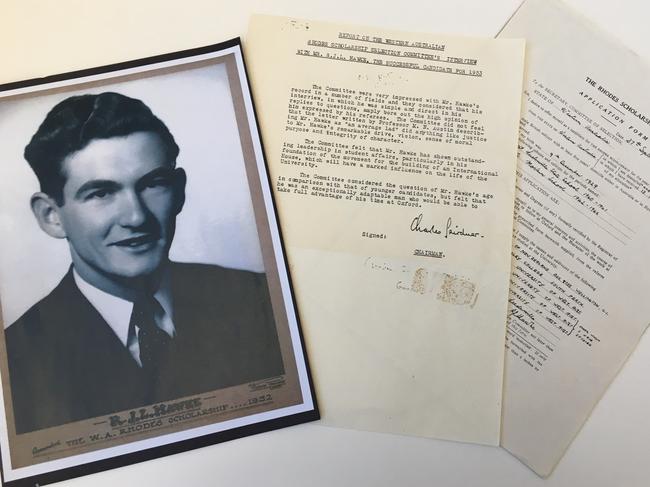

Bob Hawke is one of Australia’s best-known prime ministers – who rose to the top despite, or perhaps because of, his extraordinary personality and character flaws. New book Young Hawke examines the roots of that paradox in the leader’s early years.

In this edited extract, author David Day describes Hawke’s adventures at Oxford University in 1950s Britain: including the truth behind that legendary beer-skolling record.

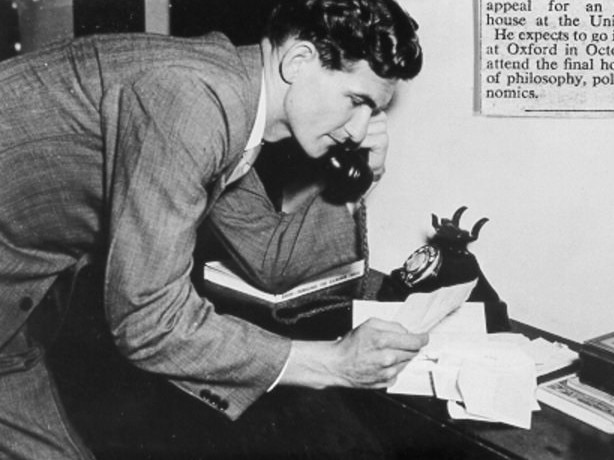

Four days after unpacking his belongings in Oxford as a newly-arrived Rhodes Scholar, Bob Hawke wrote in his regular lettergram to his parents of his first impressions of ‘the city of spires and long-haired intellectuals – boy oh boy are there some queer characters inhabiting this town’.

He’d been busy equipping himself with ‘an ancient bicycle and a very tattered gown which is a proper bum freezer only hanging a short way down the back in all its gorgeous tatters’.

As the grey days of winter closed in and the end of Michaelmas term loomed, Hawke became homesick and disconsolate. He told his parents that he was looking forward to ‘the break from the steady routine of having to prepare two essays every week’. Not only was he weighed down by the demands of his tutors, he was surrounded by students who, usually, were younger than him, despite most of them also having done two years’ national service, and who were sometimes smarter than him and not overly friendly.

Like Hawke, his fellow Rhodes scholar Hedley Bull, from Sydney, was taken aback by the frostiness of the English students, complaining that he’d twice ‘said hallo to an English student living here, but on each occasion he stared frigidly back. The lousy bastard. All the Australians complain of this.’

Rather than trying to ingratiate himself with his English counterparts, Bull noted, Hawke ‘seems much concerned to assert his colonial nationalism’. This struck Hawke’s Ulster-born tutor Tom Wilson as brashness: he noted on Hawke’s student card that he was ‘bright, efficient, a bit superficial’ and said his self-confidence could prevent him from ‘realising that he still has a good deal to learn’.

Hawke was now being matched against some of the best students the world could produce. He would also be competing with his bete noire, John Stone, who’d switched from maths to PPE and would graduate in 1954 with a first-class honours degree and a prize in Economics. Hawke was also being forced to cope without the constant affirmation that had been provided by his parents. To remedy this, he tried to find a way for his churchman father to swap churches for a year with a Congregational minister from Colchester, only to discover that the minister was only interested in going to Sydney.

Just weeks after arriving in England, and in a sign of his desperate loneliness, Hawke pressured his fiancee Hazel to give up her job, as well as her work with the church and Sunday School choir, and get to Oxford before Hawke was seduced by ‘all the delights which are available to the uninhibited Oxford undergraduate’. He warned that he’d been ‘thrust into an environment which is full of opportunities for the satisfaction of my varied tastes, to which if I succumbed in their entireties, would only succeed in taking me away from you’. He assured Hazel that he didn’t want that to happen. Nor did he want her to come earlier than they’d planned just so she could protect him from his ‘weaknesses’, but because he’d ‘made a choice about the person with whom I want to spend the rest of my life’.

That must have struck 24-year-old Hazel as somewhat strange, since she presumably thought Bob had made that decision when they’d become engaged four years earlier. Yet here he

was emphatically instructing her to ‘GET ON THAT SHIP DARLING FOR YOUR SAKE AND MINE’.

Anxious not to have him slip away, and excited by the prospect of travel and the life that might await her, Hazel immediately booked her passage. In the interim, Hawke

sent an avalanche of letters professing his love and offering practical advice about the voyage, including how to avoid men who might have seduction in mind. When the ship docked at Southampton in December 1953, Bob was the first up the gangplank, having used the good offices of the West Australian agent-general to sidestep the usual formalities. Bundling her into the two-seat baker’s van that he had bought with money sent to him by Hazel after she’d sold the car they’d owned in Perth, Hawke tootled off to spend Christmas in the small Dorset village of Loders, with family friends the Edrichs, where they feasted on two geese.

Hawke reported to his parents that he now weighed well over seventy kilograms, while Hazel was ‘getting quite a backside on her’.

Although the betrothed couple had been able to sleep together in the cramped conditions of the Edrich house, they would have more trouble doing so in Oxford, where Bob would not be able to have her in his bed, at least not when the servant came to light the fire in the morning.

After staying as long as they could in Loders, they drove back to Oxford, arriving in the pitch dark with nowhere to stay. Hawke described to his parents how they turned up on the doorstep of the Reverend Geoffrey Beck, the Congregational minister in Summertown, on the northern

outskirts of Oxford. Apparently throwing themselves on the mercy of Beck and his wife, Joy, Hawke reported that ‘they have asked me to stay with them till I go back into College next Thursday’. Beck provided a rather different account, saying that Hawke had knocked on his door the previous November, when Hazel was on her way to England, and made ‘a silly request’ for him and Hazel to ‘come and live with us’, which Beck politely declined. Apart from the question of propriety, the two-storey manse at 42 Lonsdale Road had limited accommodation, with the Becks’ three daughters in one bedroom and their young son

in the other, which was also used for occasional visitors.

Hawke had placed the hospitable minister in a quandary. In the middle of winter and late at night, Beck could hardly demand that they sleep in the van. The visitors’ book at the Beck manse reveals that Bob and Hazel stayed there for nine days, during which time the couples became good friends.

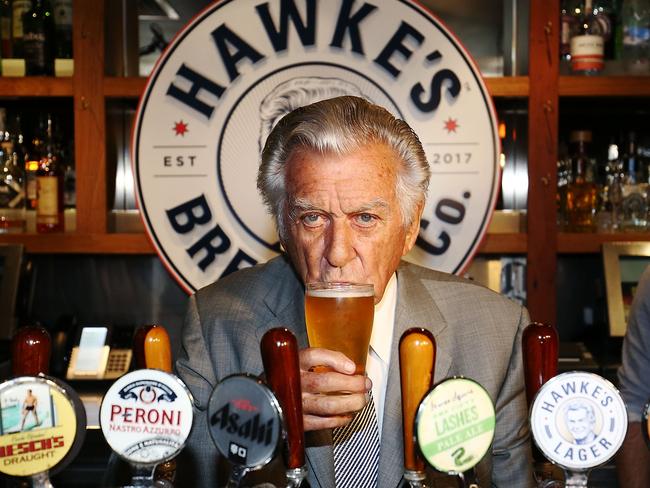

Although Beck says that Hawke didn’t drink alcohol while he was staying at the manse, there were surely nights when the bingedrinking student returned to his room the worse for wear. According to Hedley Bull, Hawke ‘would drink most nights’. One of those nights was when he downed two and a half pints of lager in record time.

There was a tradition at University College that allowed students to be challenged by the president of the Junior Common Room if they came to dinner wearing a loud tie, failed to wear their gown, spoke ill of a woman or swore while at the table. It was failing to wear a gown that saw Hawke challenged. Students would grab any available gown hanging outside the hall and walk into dinner as if it were their own.

When Hawke found his had been purloined, he went in without one and was promptly challenged. The butler was duly summoned with his stopwatch and Hawke was forced to drink two and a half pints from a pewter cup that was kept specially for that purpose. If he managed to do it within twenty-five seconds without his lips leaving the cup, and also managed to beat his challenger, he would escape the humiliation of having to pay for both their beers. The college record had been set by a South African student, who’d done it in thirteen seconds. Hawke rose to the challenge, setting a new record of eleven seconds. As he later observed with some satisfaction, the ‘feat was to endear me to some of my fellow Australians more than anything else I ever achieved’.

That may have been because Hawke ensured it would come to their notice by having it listed as a world record in the second edition of the bestselling Guinness Book of Records, which was first published in 1955 by twin brothers Norris and Ross McWhirter, who’d been Oxford graduates and members of the sport-focused Vincent’s Club, where they’d presumably shared an ale or three with Hawke, and who needed entries for their book.

His final summer in Oxford was the best one yet. Blessed with good weather, he and Hazel filled their days with tennis, swimming or punting on the river. Hawke also played cricket practically every day that summer, including a game with other players from the British

Commonwealth in a benefit match against an English county side. The practice and the playing were to no avail. That year, he couldn’t even secure a place as twelfth man in the Oxford team.

The final observation on Hawke’s college student card noted that he was ‘not very clever or industrious, but he improved a great deal as a person while he was here’. Brigadier Bill Williams, a historian responsible for the Rhodes Scholars as warden of Rhodes House, also thought Hawke was ‘much improved’ and confessed that he would ‘miss him and his brash ways’. Hawke had wanted to return home as Dr Hawke, but his passion for sport and his propensity for carousing had got in the way.

Reverend Beck recalled how, as Hawke and Hazel were taking their leave in the hallway of the Summertown manse, his wife ‘was almost ticking Bob off for the way he treated Hazel’, telling him that ‘if he was going to marry her, he’d got to behave better, not really thinking of his other girlfriends’.

However remorseful Hawke was, and however much his behaviour upset Hazel and disturbed his close friends, he was not about to change.

After all, his narcissism and his upbringing had convinced him that he was no mere mortal and subject to normal strictures. That conviction had helped both to empower and hobble him. It was a burden that he’d taken with him to Oxford, and it would return with him to Australia.

This is an edited extract from Young Hawke, by David Day, which will be published by HarperCollins on July 31.

Originally published as Hawke, Hazel and the truth about his beer-swilling university record