Why Sydney is the most resilient city in the world amid Covid lockdown

Sydney has never been a city to take a backward step or throw in the towel — this place has fought for every inch of its survival to become a global city, writes Warren Brown.

NSW Coronavirus News

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW Coronavirus News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

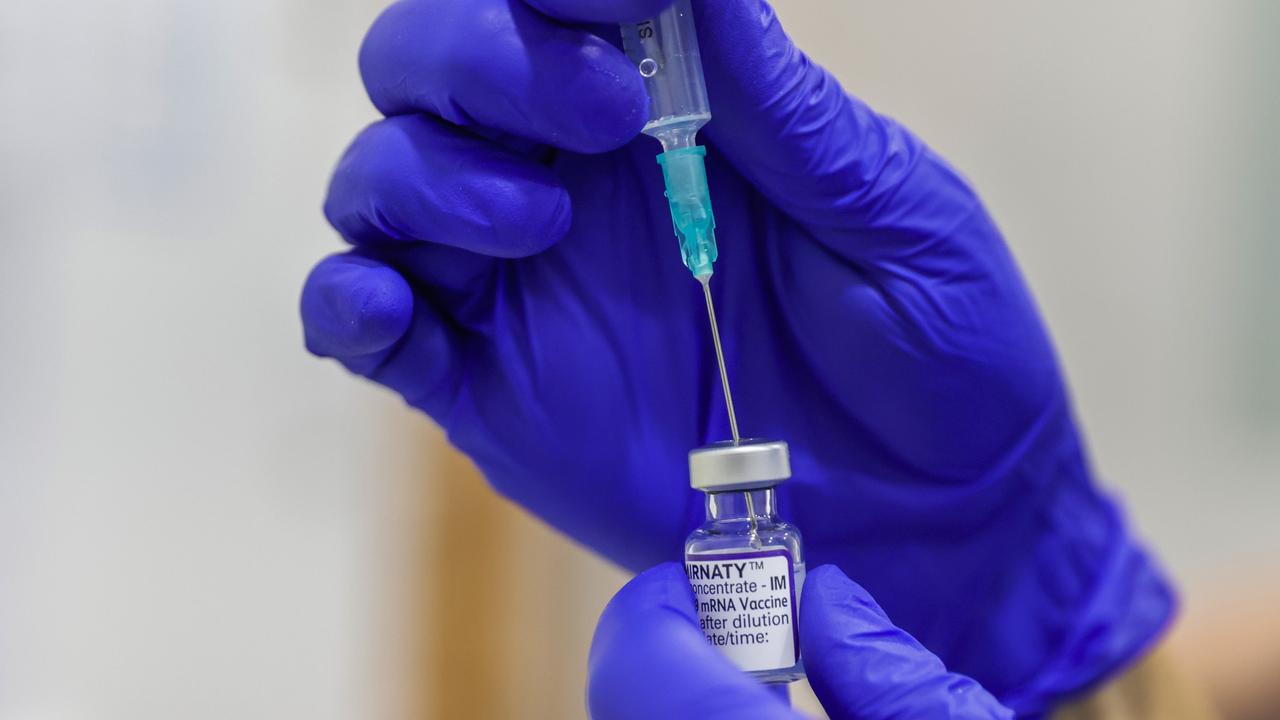

Struggling through the Covid crisis has become something of a rolling, never-ending bad dream — for a lot of us living in Sydney, a nightmare — and as each day blurs into another deadly-dull episode of tiresome routine -lockdown, vaccination confusion, social distancing, QR coding, mask wearing – it’s taking an increasingly demoralising toll in testing our patience and easygoing Australian nature.

It’s difficult to avoid spiralling into despair but despite the bleak monotony of life under the cloud of Covid-19, we Sydneysiders should instead take a deep breath, take a step back, take a reality check and appreciate that we are so fortunate to be living in this extraordinarily beautiful yet resilient city.

Sydney has never been a city to take a backward step or throw in the towel – from the moment the first hapless convict stumbled ashore on Sydney Cove this place has fought for every inch of its survival to become a global city.

We should proudly celebrate the fact that generations of Sydney’s inhabitants have lived through – and survived – far worse than the current pandemic – we can take some comfort and reassurance we’re following paths that have been travelled before.

It worth singling out a few pivotal moments when Sydneysiders had their backs against the wall and when looking at the city’s tenuous and fragile, beginning – it’s a wonder Sydney isn’t relegated as some footnote hidden within a dusty history book as one of countless failed and forgotten European colonial ventures.

Sydney is a city with its foundations built on hardship – the unexpected by-product of a hasty, Panadol solution to fix the headache of Britain’s burgeoning ‘criminal class’, by the 1780s crime spiralling to the point where decrepit ships or hulks had been converted to floating prisons packed-solid with miscreants to the point of calamity – so where on earth were they going to put all these people?

Then someone remembered Lieutenant James Cook – as was his rank back in 1770 – had set foot on some far-flung land mass on the other side of the world – a place he’d named New South Wales where botanist Joseph Banks had drawn a few illustrations of the island’s quirky plants and animals – why not send these criminals there?

It was cobbled together as a crude experiment – the equivalent of Neil Armstrong setting foot on the moon and then eighteen years later – based on his few photos – deciding to set up Goulburn Super Max on the lunar surface.

Without the slightest fanfare – in 1787 eleven ships packed with 1,420 convicts, sailors and Royal Marines slipped out of England into the unknown – for the prisoners, a brutal one-way camping-trip-in-irons for the term of their natural lives.

After a perilous 24,000 km journey this First Fleet arrived at Botany Bay where Cook had landed almost two decades earlier – but disappointed, the fleet commander and colony’s Governor, Captain Arthur Phillip, decided to explore to the north where he stumbled into Port Jackson – what we know as Sydney Harbour – and was floored by what he saw, describing it as ‘The finest harbour in the world, in which a thousand sail of the line may ride in the most perfect security …’

But for the fledgling, ill-equipped rag-tag settlement clinging to life around a waterway where the traditional inhabitants had flourished effortlessly for tens of thousands of years – this penal colony made up of Britain’s Most Unwanted had almost no chance of survival.

The majority had no education, suffering poor health and malnutrition, living in a harsh and completely foreign environment to that of England and Ireland – blazing summers, humidity, poor soil, little water, snakes, spiders — it took extraordinary commitment and resourcefulness for these impoverished, incarcerated and unprepared convict pioneers and their overseers to establish a foothold – which amazingly, they did.

Yet as the colony gradually flourished, it wasn’t always the hardships of survival in the Australian wilderness that presented a challenge – in 1808 Sydney residents lived through a dangerous armed uprising by the colony’s military garrison, the NSW Corps, which successfully overthrew the appointed Governor William Bligh – a mutiny known as The Rum Rebellion – today the equivalent would be the army removing the Prime Minister and taking control of the country.

Certainly the harsh nature of Australia’s climate and even more unforgiving administration had toughened Sydney’s population – but there were always other challenges which would test the city – and as we know, deadly disease is one.

It was a year before Federation when in 1900 a Sydney delivery man working around Sydney’s wharves was diagnosed with the bubonic plague – this virulent, lethal disease had gradually worked its way south from Hong Kong to eventually arrive at The Rocks.

Within six weeks thirty more cases were reported and swift, strict health regulations, quarantine implementations and a vigorous campaign to eradicate plague carrying rats prevented a wholesale epidemic. Nevertheless the disease continued to reappear annually for a further ten years. 263 Sydneysiders were diagnosed with the plague with 535 deaths across Australia.

When war broke out in 1914, Australia’s entire population was almost five million – less than that of Sydney today.

The declaration of war against Germany saw recruitment offices overrun with volunteers from all over Australia, mad-keen to join up and experience what would be a great adventure.

At Circular Quay mothers farewelled their sons, wives farewelled husbands, girlfriends farewelled boyfriends – the young soldiers marching down to the Finger Wharf where they would muster before being ferried out to waiting troopships ready to sail for the fighting in Europe.

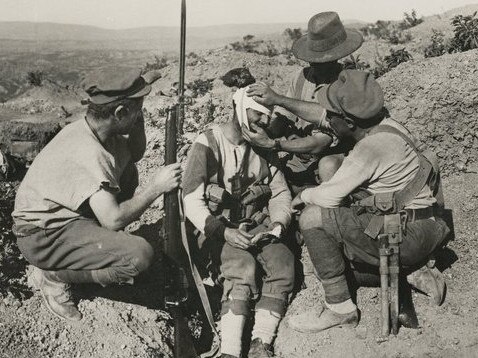

Yet this would the last place the boots of thousands of those soldiers marching through Sydney would have any physical contact with Australia – within months those boots would lie motionless in the mud of a shellscarred no-mans land or buried somewhere at Lone Pine or Pacshendale.

When we watch Gladys Berejiklian and Kerrie Chant’s daily press conference at 11am we tend to glaze over the statistics as to how many have been tested for Covid and how many have tested positive.

But can we imagine, for three whole years from 1915 to 1918 the daily message Sydneysiders received was the ghastly, ever-spiralling tally as to how many young men were now dead – killed on the battlefields of Gallipoli and the Western Front – an ultimate total of 60,000 Australians.

Having survived a harsh economic Depression during the 1890s, Sydney would grind through the desperate years of the Great Depression, the seemingly endless queues of despairing unemployed workers streaming along the Hickson Road docklands at Millers Point – begging for any kind of employment – giving the district the infamous nickname of ‘The Hungry Mile’ – today the site of Barangaroo.

Yes despite the hardships of the 1930s Sydney was able to thumb its nose at the Great Depression, unveiling one of the world’s great engineering marvels – the Harbour Bridge.

And from surviving the Depression of the 1930s, for the first time, Sydney then found itself the target in another war.

In June 1942 Imperial Japanese midget submarines slipped into Sydney Harbour attempting to sink moored American and Australian warships, in particular the American warship the USS Chicago – instead sinking the depot ship HMAS Kuttabul killing 21 sailors.

At midnight the Japanese submarine I-24 surfaced just off South Head and fired ten shells into Sydney, nine of which landed in the Eastern Suburbs.

The attack shocked and terrified Sydneysiders, many of whom were convinced it was the prelude to a Japanese invasion – people fled to the Blue Mountains and regional towns in fear – yet to their credit, even more residents were spurred on to enlist in volunteer defence organisations.

When the grim conditions and constraints of fighting the Covid pandemic seem too much for us to bear, when there’s a feeling of hopelessness and it seems there is no light at the end of the tunnel – it helps to take stock of the seemingly insurmountable challenges Australians before us overcame.

Sydney and its people are tough and will always bounce back – we’ve been through worse …

More Coverage

Originally published as Why Sydney is the most resilient city in the world amid Covid lockdown