Buy now, pay later: something will eventually have to give

From Afterpay to Sezzle and Zip, the business model of buy now, pay later has one major problem.

QLD Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

From Afterpay to Sezzle and Zip, the business model of buy now, pay later has one major problem. The more customers they get, the more money it costs.

The headline numbers all point to turbocharged customer and revenue growth and until recently their share prices reflected this.

But the fast rate of cash burn for buy now, pay later points to more players likely to do it tough, particularly as interest rates here and around the world start rising.

This is expected to drive a fresh shake-out across the sector which has already seen a share price battering. Two major players Zip and Sezzle have already confirmed merger talks, and Ahmed Fahour’s Latitude has tabled an offer to acquire the buy now, pay later business of Humm.

While many of the ASX-listed buy now, pay later players are in a race for growth, the reality is that in their core lending businesses they are simply burning more cash than they are producing. The difference is being made up by using low-cost debt or more expensive share equity.

But as credit charges rise and share prices fall, something will eventually have to give.

A quick scan at the recent cash flow statements show worrying rates of cash burn across key listed players, with the cost of acquiring new customers coming at a far higher cost than servicing existing customers.

While it is normal for more cash to go out the door during the growth phase, the funding settings need to be finely balanced particularly in a high inflation and higher interest rate environment.

A rate rise will certainly drain the cash reserves of the BNPL businesses far quicker, given many are propped up on lines of credit.

Splitit, which piggybacks off existing credit cards for buy, now pay later-style instalment payments, experienced cash burn of $US31.3m ($44.5m) during the December quarter and $US52.4m for the past year, according to figures released on Monday.

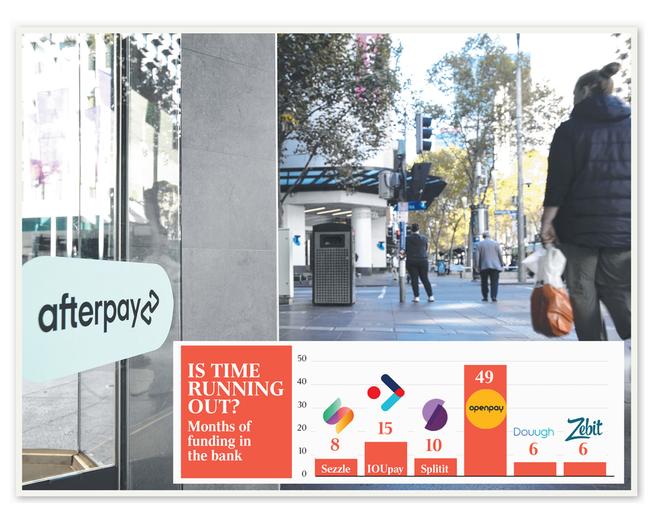

Most of the payments were to merchants, or retailers, for the funding of the instalment payments. Splitit has nearly $US29m worth of cash in the bank at the end of the quarter. It also has $US83.6m left on a $US150m line of credit with Goldman Sachs which is due to mature two years from now. Between cash on hand and a credit line it has a little over 10 months worth of funding available.

Splitit’s interim chief executive John Harper says the fintech has been repositioned so that it does not have a heavy reliance on consumer marketing costs, and does not need to price to cover significant consumer defaults.

“This model provides operating leverage at scale and a pathway to sustainable and profitable growth at superior margins,” says Harper.

The bigger Sezzle experienced cash burn before financing of $US40.9m for the December quarter and $US72.2m for all of last year.

Sezzle has a little over eight months worth of funding available at current growth rates, including its $US250m revolving line of credit with Goldman Sachs and US alternative financier Bastion. During the December quarter Sezzle’s total revenue grew 15.7 per cent to $US32.9m.

Elsewhere, junior BNPL play Douugh, which is planning on launching cryptocurrency services, including a crypto savings wallet, saw $6.3m head out the door in the past six months with only $406,000 in revenue generated over the same period. More than 40 per cent of Douugh’s costs were on marketing and advertising. Douugh has six months of funding available, including the proceeds from a recent $5.53m equity raising.

IOUpay’s most recent quarterly accounts saw $7.7m in cash fly out the door during the September quarter mostly on payments to merchants. During the same period it had just under $2m in customer revenue. With $40m cash in the bank IOUpay has around 15 months worth of financing available.

Zip, which ranks as the fourth biggest player in the US BNPL market has a more comprehensive funding program with more than $431m in available credit to back transactions. Zip, which is not required to file quarterly cashflow reports, expects another $200m facility to become available by the end of September.

Brokerage Citigroup recently slashed the earnings forecasts for Zip to reflect slower growth for cooling e-commerce spending and a shift to consumers buying services over goods. There is also caution of higher bad debts coming through, particularly as economic stimulus programs unwind and inflation takes hold. At the same time in the US, a student loan repayment moratorium is scheduled to come off in May. It was previously set to finish in January.

Before its recent $39bn merger with Jack Dorsey’s Square, Afterpay had more than $1bn in funds available both in Australia and in the US from a range of banks including National Australia Bank and Goldman Sachs.

But in its last full year as a standalone company Afterpay burnt $571m worth of cash from its core operations. In the past three years nearly $1bn went out the door. It made up the difference through borrowings and raising cash by issuing more shares while prices were surging.

“One thing that higher interest rates do is that these cash burn companies face increasing pressure to get to profitability. As liquidity gets removed a little bit, then opportunities for expansion become a little bit more difficult,” one leading fund manager said on Monday.

At the same time barriers of entry are coming down across BNPL with competition heating up across the board.

Al Kelly, the chief executive of global credit card giant Visa last week noted his business was now clipping the ticket on both sides of the buy now, pay later transactions. Not only is Visa providing the infrastructure for payments, but “fintech consumers also continue to use their cards to pay off their instalments,” Kelly told an investor briefing.

More than a decade ago, non-bank mortgage lenders were the finance disrupters, stealing the march on major banks, undercutting with fast-paced growth and cheap interest rates. This worked fine until credit markets started to seize up and their businesses models that were built on short term funding were exposed.

The most famous of these was RAMS home loans group that imploded just weeks after its ASX float in July 2007. When money markets froze it was unable to fund its fast growing mortgage book. The business was carved up with the Rump of it sold to Westpac.