Convincing travellers to stop in Outback Queensland remains a challenge for tourism bosses

Tour guides and baristas don’t really have the same ring, but they could prove just as important to the future of the Qld Outback as farmers and drovers

QBM

Don't miss out on the headlines from QBM. Followed categories will be added to My News.

They’re the jobs that built the Outback – farmers, drovers and shearers. Blood, sweat and tears of tough men and women soaked in to the red dirt of one of the toughest environments on Earth, committed to Outback folklore.

Tour guides and baristas don’t really have the same ring, but they could prove just as important in the future of the Outback.

As traditional rural industries such as farming and mining face challenging times, tourism has emerged as a ray of hope to keep Outback communities alive.

Drought (despite February’s flooding rains), the increased mechanisation of farming and mining and the cold, hard fact that more farmers are no longer able to make a living off the land, mean there are simply less jobs in the Outback’s traditional industries than there used to be.

Last year, there were less than 70,000 people living in what could be called ‘Outback Queensland’, a decline of almost 10 per cent in the last five years.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, agriculture remains the region’s biggest employer, but farming jobs have dropped nine per cent in five years.

Mining sector jobs have dropped almost 16 per cent in the same time period.

But tourism is bucking the trend. Almost 4000 jobs are now ‘supported by tourism’, with the industry providing almost 3000 directly – at a growth rate of almost 20 per cent over the same five years that mining and agriculture job numbers have plummeted. Financially, tourism pales next to the two economic powerhouses. Last year, mining was worth $32 billion to the Queensland economy and agriculture $10.6 billion.

Outback tourism is worth less than $1 billion, but industry leaders believe it brings something far more valuable.

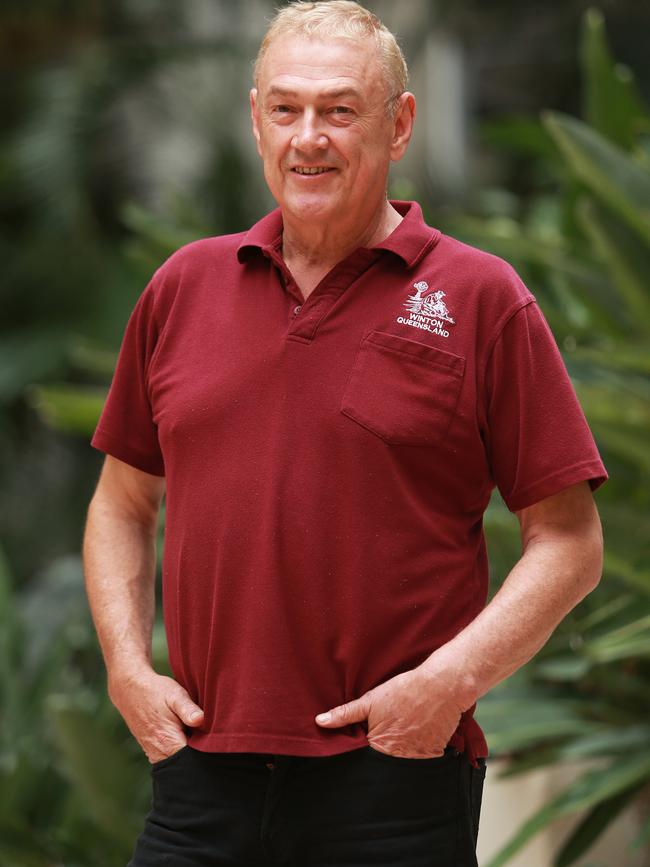

“Soul,” says Peter Homan, general manager of the Outback Queensland Tourism Association.

In an era when regional airports are routinely filled with FIFO workers heading back to their real homes, tourism can create a sense of community that mining never will.

“We want to arrest that decline in population and tourism can create that sense of community,” Homan explains.

“You see people taking pride in their community, it means they want to stay there and if there are visitors then there are jobs. It (tourism) can really galvanise the whole area and gives a lot of soul to the place.”

He points to Winton and Longreach as examples of communities that may well have withered without the impact of tourism.

“Winton is a perfect example,” he says. “There’s the Waltzing Matilda Centre, the Australian Age of Dinosaurs museum which are fantastic tourist attractions and that then flows on to everything else, the hotels, the cafes, the bakeries, the petrol stations.

“Winton is really punching above its weight, but if it wasn’t for tourism, it would be little more than a pit stop on your way somewhere else.”

He wants people from rural communities to start thinking of tourism as a viable career path.

To that end, he and other outback community leaders are lobbying for hospitality classes to be offered at regional trade colleges that have traditionally only offered courses in agriculture.

“The jobs are there,” says Homan.

“But if you need to bring in chefs or baristas from the cities that costs money.

“It would be great if we could get people in these courses out here instead of having to move away, but right now the opportunity to train here is almost non-existent.”

That could change, with the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries currently considering changes for education programs at agricultural training colleges in Longreach and Emerald.

Submissions, which included proposals from the tourism sector, closed last week.

A spokesman for the department said a project management office for the future of the colleges was looking for proposals ‘to create reinvigorated training opportunities’ and ‘to consider alternate commercially sustainable future uses for the college assets’.

Longreach’s Dan Walker is one who quickly recognised the potential of tourism when he and his brother James started hosting visitors at their family’s Camden Park station.

“In farming you are so exposed to the conditions of the climate, so we knew we had to diversify,” says Walker, a third-generation farmer on Camden Park.

“I knew I wanted to meet people and entertain people because sitting on the farm bike was pretty lonely.”

When they started running farm tours in 2014 they received only a handful of visitors, but they now get 3000 a year.

The traditionally quiet summer season, which used to attract only a few dozen tourists now sees up to 500.

And he knows what is good for Camden Park is good for the region.

“We think if we can keep them in town for an extra night then that helps everyone.”

The Queensland Government has also recognised the importance of the industry to the region, dubbing 2019 as ‘The Year of Outback Tourism’.

In the year ending December 2018 total overnight visitor expenditure for the region was $644.8m – 63 per cent higher than it was five years ago.

But while tourism has undoubtedly played a role in revitalising communities, huge areas of potential remain largely untapped.

Last year just 29,000 of the state’s 2.7 million international visitors made it to Outback Queensland.

It takes a long time to get to (a flight from Brisbane to Mt Isa takes longer than flying Brisbane to Melbourne) and airfares are prohibitively expensive for the backpacker crowd while the vast distances discourage road trippers.

A place like Boodjamulla (also known as Lawn Hill Gorge) is a World Heritage-listed wilderness of extraordinary beauty. But it doesn’t attract anywhere near the visitor numbers of Kakadu or Uluru (some locals wistfully say that is a good thing). Convincing travellers prepared to fly for hours to the Red Centre that they should stop in Outback Queensland remains a challenge for tourism bosses.

Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk is a fierce advocate of the Year of Outback Tourism initiative and says highlighting the struggles of regional communities can inspire a call to arms to increase visitor numbers.

“As we saw in the drought and the floods there is a tremendous will to help people in remote and regional Queensland,” she says.

“The Year of Outback Tourism is just another way to bridge the distance and show people we’re a lot closer together than they realise.

“And, let’s face it, you’ll never feel a warmer welcome, never find a wider horizon, never see a brighter sky or a better place to take your children than Outback Queensland.”