Mid-market fashion retail is a bargain bin fire. How much worse can it get?

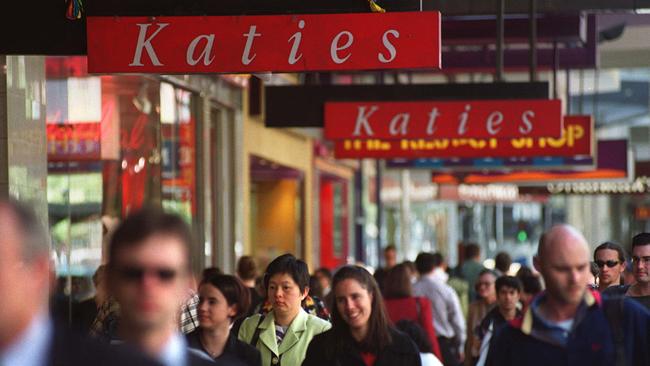

Big retail names like Katies, Noni B and Millers have collapsed as selling clothes to older, mid range shoppers is tougher than ever. How much worse can it get?

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Olivia Wirth and Alice Barbery are perfectly placed to observe the hollowing out of the nation’s middle-market fashion and apparel sector, where once powerhouse names like Katies, Noni B and Millers loved by loyal shoppers are in the corporate graveyard.

Retail executives instinctively know any retailer - including their own - is one step away from terminal decline if they misunderstand their shopper, take their business for granted or try to dupe them on quality and price.

Cost-of-living pressures are not the whole story: Shein’s $19.95 coats and Amazon’s $21.99 denim are indefatigable forces.

Wirth, the executive chair of department store owner Myer, and Barbery, the CEO of youth-fashion chain Universal Store, are applying very different strategies to avoid the fate of Katies in their respective demographics.

“It is obviously a tough environment that we’re operating in, and we know that discretionary income is tight, and that obviously has an impact on retail across the board,” Wirth told The Australian.

“We’ve done a big diagnostic on customers from age 16 through to age 80 and we are very clear about the opportunity. Opportunity exists in every single life stage and you have just got to be very focused on what their needs are, very focused on what the products that you’re offering, about what your value proposition is, and be really clear on who your customer target is.”

Barbery, whose Universal Store chain is reporting some of the strongest sales growth in the listed retail space thanks to its resonance with younger consumers, is similarly obsessed with her shoppers.

“I just believe it’s customer responsiveness, how quickly you can respond to customers needs, how attuned you are to the occasions for ‘wear’ that your customers have, that you have the right product, in the right quantities at the right time, and you have an engaged team.

“So the customer is your primary objective and that No.1 focal point of every conversation, this is an advantage in challenging times, and so it can definitely help you take market share when consumers are being more cautious.”

Ian Bailey, the boss of Kmart and Target, which has made the middle-market profitable in the fashion and apparel space with its trendy and affordable range, puts it simply: “We are now in the period of winners and losers”.

“I think first of all, there’s more competition now than there’s ever been. Whenever there is a period where competitive tension increases, then you need to make sure that you’re better than the rest. So certainly, when we think about the Kmart and Target brands we’ve been working very hard to improve the proposition in apparel, because we can see that the competition is intense.

“But equally, we can see there’s a big opportunity we can get it right. And I do think we’re in a period now of winners and losers, particularly in this apparel space.”

Nobody wants to be stuck in the middle.

The retail pack is making its own strategic bets on how to survive. Myer is finding solace from diversification, buying up apparel brands like Just Jeans and Portmans from Solomon Lew’s Premier Investments and looking for growth in categories such as beauty, home and menswear. At Universal Store, Barbery’s customer is free of mortgage payments, school fees and still living at home. That deliberately narrow focus means they have money to spend on new clothes.

“So the youth market is somewhat shielded from the challenges of interest rate hikes and cost of living pressures,” Barbery says, reflecting on her demographic. “I’m not going to say they’re completely shielded, but they’re more so. Socialising for young people is still a primary concern... socialising is so important when you’re in your 20s and teens and hanging out with friends, and so it does give us an advantage in that regard.

“That middle market, 40-plus age group is hard. When you’re in that almost retired phase, a bit older, and you’ve got a pretty full wardrobe, your kids are trying to make their payments on their mortgages or escalated rent, you’re always going to choose your family over a new dress.

“And you know, when you’re 19 and 20, you just don’t have those pressures.”

For Bailey at Kmart and Target, owned by Perth conglomerate Wesfarmers, it’s about giving these shoppers quality and value for money. He knows you can’t skimp on either and expect to survive.

“If you buy a T-shirt it doesn’t matter where you buy it from, you want it to fit, you want it to be the right colour, you want it to just go in the washing machine and come out the same size. It doesn’t matter if you’re spending $5 or $50, and I think what happens is, if you are spending $30 and it doesn’t perform, you’re seriously disappointed as a customer.”

The collapse late last year of Mosaic Brands, owner of household names like Katies, Millers, Rivers and Noni B, put a spotlight on the current struggles brands face. It also sent a warning to other retailers; anyone could be next.

But Mosaic Brands came as something of a shock to the sector. Such was the demise of the retailer, it ended its corporate life with more than $300m in debt and its most famous brands - like Katies, which was an iconic and profitable label at its height - couldn’t even find buyers. They were consigned to the dustbin of history.

The South African owner of Country Road Group recently declared Australia was in the midst of a “retail recession”.

However, the truth is more nuanced than that.

“We’ve actually just come out of a retail recession,” says James Stewart, KPMG’s leader on retail and the consumer.

“Our economics team says that we did nine quarters of negative growth in retail and the last quarter was the first time we’ve had positive growth in ten quarters. We were in a retail recession, yes, but we’ve just sort of stuck our nose right on the other side.”

The latest KPMG Retail Health Index indicated momentum has shifted positively and the prospect of normal conditions is within reach: the retail sector returned to good health in the second quarter. The index rose 0.57 points, from -0.87 in the third quarter to -0.3, driven by the lowest wage growth since 2022, easing inflation, stronger consumption, and a boost in consumer sentiment ahead of the February 2025 rate cut.

To be sure, many retailers are still struggling, and failing, and Stewart believes some of these can be laid down to “own goals” by management.

“We don’t know to what extent some of these brands have committed some sort of own goals in their own sort of management of the business. So there’s always an element of management of the business when you see those retailers collapse, and sometimes that’s because they’ve made the wrong strategic calls, or they’ve sort of positioned themselves in a different way.”

Stewart sees the middle market of fashion and apparel as tough.

“You really have got to know who your customer is very precisely, and got to be able to then really have a laser focus on what and who your customer is, particularly in fashion.

“What’s the engagement level you’re trying to have with them? In other words, what is the emotional connection, but then backed up by how good is the product, how good is the value, how good are the price points and because, remember, it’s the emotional engagement that brings people back.

“But a lot of the middle market brands, they’re not going to get down to the Kmart price points.” No wonder Kmart’s Bailey is smiling.

But even he is up against pressure, and especially from online players such as Chinese marketplace Shein, Temu and Amazon.

“I think the first thing I’d say is you cannot underestimate the impact that Shein is having on the fashion and apparel market, they might only be clipping a few per cent here or there, but they’re making very significant dollars in the Australian market,” says Stewart.

“And that’s only one example. So the online play, I think, continues to have an impact. And Shein even though it has been around for a while it is relatively new to the Australian market, and they’re doing, I understand, pretty big numbers here.”

Barbery, who has more than 30 years of experience in the retail sector including stints with GAP, Colorado and Virgin Airlines, believes it was a different market when Katies ruled womenswear.

“There was no online shopping, there was very limited competition.

“And for those brands - and it’s very sad, I hate to see anybody disappear, it’s not good for retail - but their market is the mortgage market, or the market that’s helping their kids with their mortgages, and therefore they will make family decisions over a new outfit, where the youth market doesn’t have that drain on their wallet.”

Stewart’s firm KPMG handled the Mosaic Brands administration, and while he sees hope for those that genuinely connect with shoppers, he knows it is becoming increasingly tough.

“There’s swings and roundabouts if you look at great global fashion brands. And if you look at Australia, look at Sportsgirl for example, there’s plenty of examples of Australian brands that have gone through seasonal fluctuations. Sportsgirl in the 1980s was on fire, in the 90s, it really struggled, and then Naomi Milgrom turned it around again. So I don’t think those brands necessarily lose their brand equity, but they might lose touch with their market.”

With one caveat: “It really comes down to the vision, the creative vision of the owner.”

Originally published as Mid-market fashion retail is a bargain bin fire. How much worse can it get?