How the once economic basket case of Greece is turning investing on its head

When most people think of emerging markets the first thing that comes to mind is the meltdown of the Asian currency crisis. It’s time to think again.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

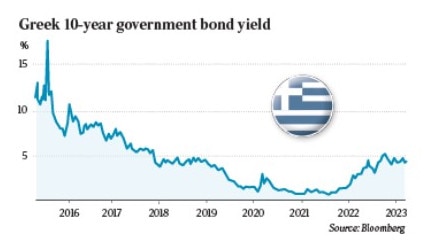

A decade ago Greece was the financial basket case of Europe.

The country that was ground zero for the eurozone debt turmoil is now a model citizen. Indeed with the global economy facing a recession and governments everywhere under strain, Greece is moving steadily toward a credit ratings upgrade — back to investment grade from junk – potentially as early as this year.

Long-term Greek bonds are now rated a lower risk bet than Italian ones, and Athens has in recent years issued a 30-year bond – something once unthinkable for normally risk-averse debt investors.

“They’re going to be the story of the year,” says Marshall Stocker, the co-global head of Morgan Stanley’s emerging market debt fund.

Leading up to the financial crisis, Greece did “everything wrong”, says Stocker, whose fund is a large holder of Greek debt.

The government had borrowings hidden through off-balance-sheet structures. It overspent funds, reforms were going nowhere and they came close to dropping the euro.

The politics was deeply fractured too.

But through the middle of the crisis and with the backing of the European Union, Athens seized on an opportunity to restructure its debt, to push out repayments over the long term, and in doing so lock in relatively low interest rates.

This gave it enough breathing room and removed worry about a repayment event so they could get the reforms done, Stocker says.

A centre-right government has since secured a political consensus and is pushing ahead with the country’s latest round of privatisations. Athens could move to an investment grade as early as this year, which would have a major implication for the country and an uplift for its equity markets.

“We can have a country just about fall off the side of the earth … With the right intervention it can take a decade and it can be painful, but it can be done; you can get back to investment grade,” Stocker tells The Australian.

A major study released by the Boston, Massachusetts-based Stocker in recent months found a direct link between governments introducing policies enhancing economic freedom resulting in improved yields (lower borrowing costs), and lowered the risk of default. The paper analysed bond market performance, including the risk of default across 165 countries for the past two decades.

Significantly, it wasn’t the absolute level of economic freedom itself that drove improved outcomes for investors but the steps that countries took to improve economic freedom.

Stocker says the study also found that countries which have policies that lead to deteriorating economic freedom generally increase their default risk. Their position becomes more vulnerable as macroeconomic factors worsen.

“Simply, when a country’s economic freedom goes up, the cost of its capital goes down,” Stocker says.

Rethink on bonds

The paper was significant because it gave investors the evidence needed to take another look at how they approached emerging market bonds. It was a road map of how to look at the high returns on offer from emerging markets, while spotting the candidates for the riskier exposures.

The study was released as superannuation funds are rethinking how to invest in a high-inflation environment. This means they are starting to take another look at emerging markets as they search for outperformance.

Emerging market debt, which takes in countries from South-East Asia, central Asia and Latin America, is almost 30 per cent of the global debt market today. But big funds hold just a fraction of this allocation.

When most people think of emerging markets the first thing that comes to mind is the meltdown from the Asian currency crisis of the late 1990s.

Stocker points out the global economy has experienced several major shocks since then but apart from some individual country reactions, emerging markets have remained resilient.

The reason is the debt structure is almost inverted to what it is today. Previously, the bulk of debt was held in US dollars with small amounts in local currency, whereas most of the debt they hold today is in local currencies.

But with the latest market strains, Stocker says emerging market countries moved early and went hard hitting inflation. And their balance sheets stayed intact with pandemic-linked borrowings constrained compared with developed economies across Europe, US and even Australia.

“Back when we were debating whether or not inflation was transitory, I don’t think you could have found an emerging market investor that said inflation is transitory.”

“We know that inflation lasts for years once it gets going. There’s various reasons for it and all of them are difficult to address, whether it’s supply side inflation, or demand side inflation.”

“The emerging markets – their central banks – raised rates very aggressively; much more so than developed markets”.

Brazil for example has a policy rate of 13.75 per cent more than three times Australia’s cash rate or more than double the US policy rate.

This means the real interest rate yield differential – that is the policy rate minus forward expectations about inflation – it’s positive. Indeed the differential between the real yield and the policy rate is the highest since the global financial crisis, without the GFC-like conditions.

“Emerging markets are acting like developed markets and developed markets are still struggling to get to positive real rates – with inflation still higher than the (cash) policy rate.”

On a risk-adjusted measure, Stocker says the opportunity to collect yield is much more compelling in emerging markets, because inflation won’t eat away at nominal yield, as it is in developed markets.

The consequence of being so assertive about inflation is that the foreign exchange rates for emerging markets countries have proven remarkably resilient.

“The reason you put emerging markets in your portfolio is because after the Berlin Wall fell, everybody knows what economic systems work and which ones don’t.”

Argentina’s woes

There are still pockets of deep risk. At the other end of the scale from Greece is Argentina, where annual inflation is now running past 100 per cent and there are few signs of it getting under control.

Last month ratings agency Fitch downgraded Argentina’s debt rating to “C” suggesting that it thinks a default is imminent.

Adding to Argentina’s woes is the repeated willingness of the International Monetary Fund to bail out the country with loans. It’s keeping it on financial life support which is undermining the “shock therapy” needed for it to change, he says. And there is little political appetite to change.

“Argentina is in this perpetual state of economic crisis. And we find that improvements in economic institutions more frequently happen in the absence of crises when nobody’s looking,” Stocker says.

Argentina was nearly the richest country in the world at one point in time, and what we know is that there seems to be a strong relationship between political systems and changes in economic institutions.

“There is a tension between the political system and the necessity of breaking a social contract in a country that has incredibly poor economic policies. It’s partly that they’re struggling in a cycle that doesn’t give the leadership enough time to shift to better economic policies.”

His fund too is cautious toward China. Here he thinks the recovery of the economic giant is going to be muted and there are still some structural headwinds with respect to rebalancing consumption and investment. And while Beijing is pushing ahead with some “pragmatic liberalisation” such as the removal of tough Covid-era policies, there are few signs of an ideological commitment to economic liberalism.

“Emerging markets are in this multi-decade process. And it’s not uniform country by country. And sometimes they take a step backwards, a decades-long process of adopting rule of law, getting the government out of private enterprise, simplifying the regulatory environment, and engaging in free trade,” he says.

“When they do that their economic freedom goes up. When that happens the yield spread contracts, the cost of capital goes down. And that’s your total return. And everything in the country becomes more valuable.”

johnstone@theaustralian.com.au

Originally published as How the once economic basket case of Greece is turning investing on its head