‘More cash to splash’: RBA poised to put more money in your pocket

For five years, the Reserve Bank has been worried about one thing. Now it has flip-flopped and it means more cash to splash for all of us.

Interest Rates

Don't miss out on the headlines from Interest Rates. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Australia’s recent run of low growth came as a “bit of a surprise”, Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe said last night as he indicated he was ready to cut interest rates again.

“We did not expect this slowdown, so it has come as a bit of a surprise,” Mr Lowe said, addressing the recent collapse in Australian gross domestic product growth to just 1.4 per cent in the year to June.

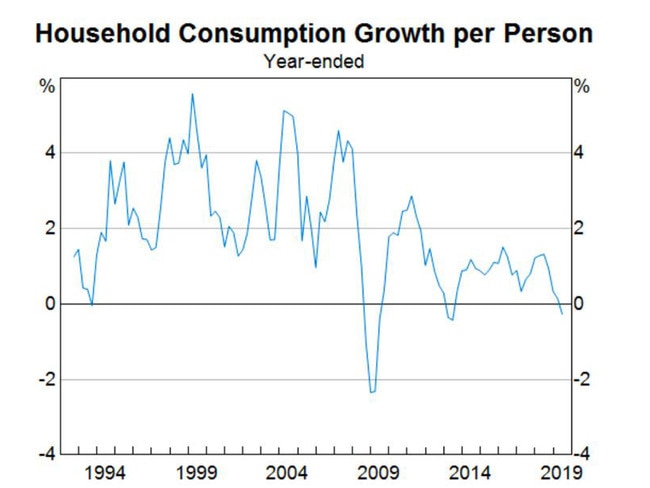

With rising unemployment and weak wages, Australian economic growth has been clearly insufficient. In fact, if your household feels like it had to tighten the belt over the last year, that feeling might be justified. Growth in per capita consumption has turned negative, as the next graph shows.

Negative growth in consumption suggests falling standards of living. That’s not what we have come to expect.

This weakness is driving the RBA governor to cut interest rates. He never actually tells Australia what the RBA will do at its board meetings (the next one is next Tuesday), but he likes to drop big hints, and in last night’s speech, the hints were big and broad.

“Further monetary easing may well be required,” he said, noting that since every other country was slashing their rates, we would have to do the same or suffer from a higher exchange rate.

Australia’s interest rates have already been slashed, from their record low level of 1.5 per cent over the past several years, down to a new record low of 1 per cent. Now it looks like we’re going to creep even closer to zero.

This is actually good. We should hope lower interest rates kick the economy into gear — although they won’t do it on their own.

WHY WOULD LOWER INTEREST RATES HELP?

Interest rates should work like an accelerator on the economy. The theory is, when the interest rate on borrowing and saving is low, businesses and people should borrow more and spend more, while saving less. That should get the money flowing out of our pockets and through businesses, which in turn hire more people, creating a virtuous cycle.

In practice, this theory works by reducing people’s mortgage repayments, meaning they have a bit more spare cash to splash around. (Of course lower interest rates also reduce the returns people make on their savings, but Australia has much more mortgage debt than it does savings, so the overall effect is positive.)

A lower interest rate also lowers the exchange rate, which is great for our manufacturers, miners, tourism businesses and other exporters. When the Aussie dollar is under 70 cents we tend to holiday in Cairns not California, and buy more Australian-made. That is good for the local economy.

THE BIG PROBLEM

The big risk with lower interest rates is if they blow up the housing market again. In the past five years, the RBA was reluctant to cut interest rates because it was very worried about house prices being in a bubble. Now it seems to have flip-flopped. Mr Lowe said yesterday he was not particularly concerned about house prices.

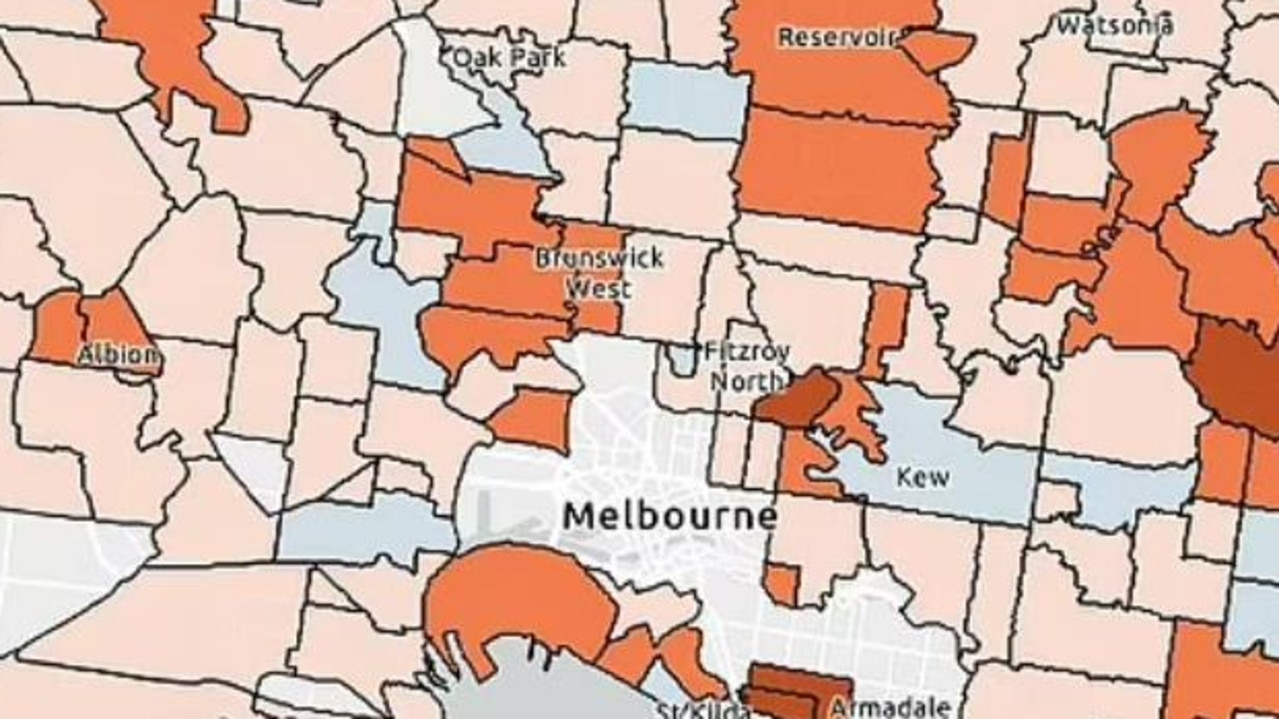

The recent house price falls have taken any pressure off the decision to cut rates, apparently. But Australian household debt is still very high. And house prices have begun to rise again in Sydney and Melbourne, where auction clearance rates are back at highly elevated levels.

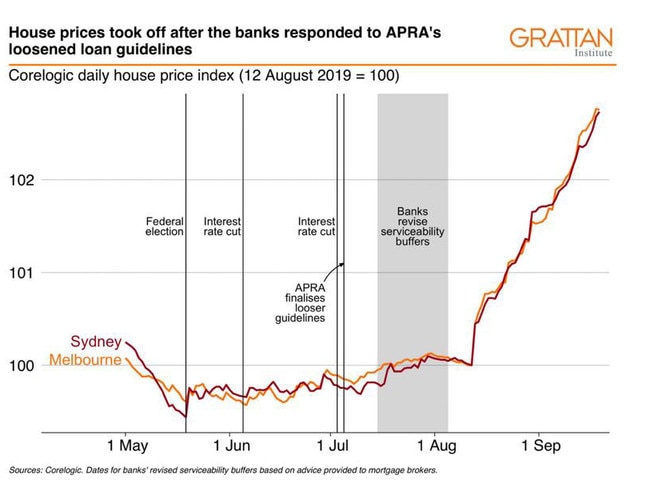

If house prices quickly run back up and reverse their falls, people will criticise the RBA. I would usually have thought that was justified. But a new piece of scholarship by the Grattan Institute hints that the RBA might not be entirely to blame. Instead it might be the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, the banking regulator.

The Grattan Institute, an independent think tank, recently published this graph. It shows that the recent very sharp uptick in CoreLogic house price data from Sydney and Melbourne actually doesn’t line up well with interest rate cuts.

Instead, it lines up with changes that happened in July, where Australia’s banking regulator relaxed rules about who banks would lend to, and how much they would lend.

Before July, banks could lend only to people who had the ability to pay back the loan if the interest rate went up to 7.25 per cent. The size of the buffer has now been cut by most banks. Westpac has now set its buffer at 5.35 per cent, meaning more people can get loans, and loans are higher.

“The changes being finalised today are not intended to signal any lessening in the importance APRA places on the maintenance of sound lending standards,” APRA chair Wayne Byres said at the time.

Whether sound lending standards have slipped or not, the timing is hard to deny. From the daily housing market data and the auction clearance rates, it is clear the Sydney and Melbourne housing markets have a new vigour. And that could quickly rub off on the rest of the country.

HAVE OUR CAKE AND EAT IT TOO

The implication of this is quite good, because it suggests we can have our cake and eat it too. The RBA can use lower interest rates to try to keep the economy moving, and if house prices do keep rising and start to get out of hand, we can use lending rules to control them. We just need to hope the politicians in charge of those lending rules have the courage to use them.

Jason Murphy is an economist. He is the author of the new book Incentivology. Continue the conversation @jasemurphy

Originally published as ‘More cash to splash’: RBA poised to put more money in your pocket