RBA caught between a rock and hard place on inflation

It feels like Groundhog Day for Aussies as the RBA twists the knife further — but the truth is Phil Lowe is caught between a rock and a hard place.

Interest Rates

Don't miss out on the headlines from Interest Rates. Followed categories will be added to My News.

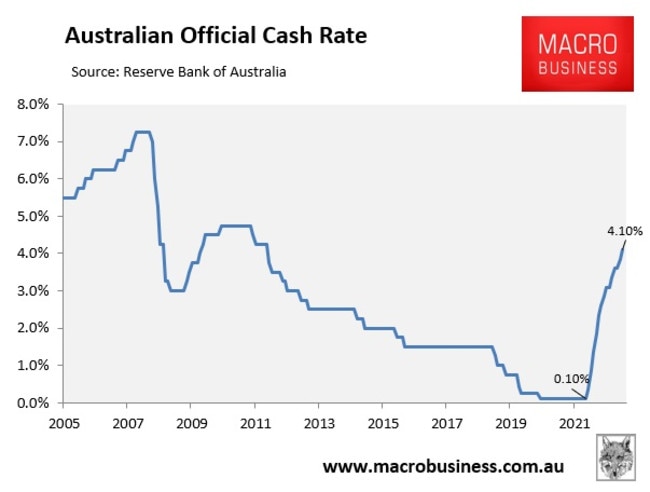

It feels like Groundhog Day for Australian mortgage holders, with the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) on Tuesday twisting the knife further with another 25 basis point increase in the official cash rate (OCR) to 4.10 per cent.

The move lifted the OCR to its highest level since April 2012 and represents the sharpest increase in the nation’s history:

In his statement accompanying the decision, Governor Phil Lowe noted that “inflation in Australia has passed its peak, but at 7 per cent is still too high and it will be some time yet before it is back in the target range”.

“This further increase in interest rates is to provide greater confidence that inflation will return to target within a reasonable time frame,” he said.

Governor Lowe warned that recent data indicated “that the upside risks to the inflation outlook have increased and the Board has responded to this”, in particular “while goods inflation is slowing, services price inflation is still very high and is proving to be very persistent overseas”.

Governor Lowe also flagged that “some further tightening of monetary policy may be required to ensure that inflation returns to target in a reasonable time frame, but that will depend upon how the economy and inflation evolve”.

Before ending his statement with “the Board remains resolute in its determination to return inflation to target and will do what is necessary to achieve that”.

Pity the mortgage holder

Once the rate hike is fully passed on by lenders, Australian variable mortgage holders will be paying around 50 per cent more in monthly repayments than they were in April 2022 immediately before the RBA’s first hike.

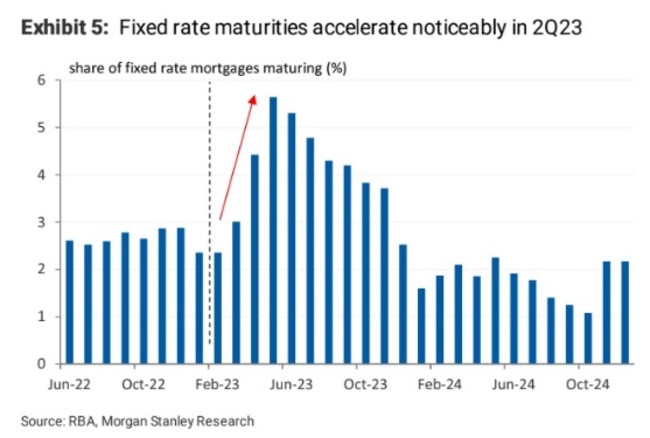

There are also around 500,000 fixed rate mortgages that will expire over the remainder of this year who will reset from ultra cheap rates of around 2 per cent to rates of around 6 per cent:

In turn, average mortgage rates will continue to rise across Australia, even without further official rate hikes from the RBA.

Betashares chief economist David Bassanese told The Australian in April that “the higher than usual expiry of fixed-rate mortgages over the coming two years will result in de facto policy tightening (at least on the mortgage sector) equivalent to around one third of the policy tightening already seen over the past year”.

That’s the equivalent of at least 1 per cent of rate hikes that are still to flow through to mortgage holders once the fixed rate mortgage reset runs its course.

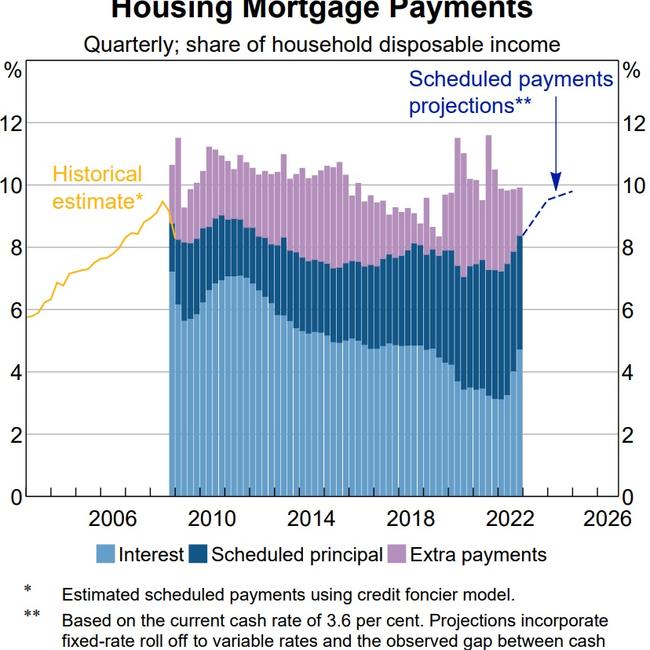

The impact of the fixed rate reset is illustrated in the next chart from April’s RBA Financial Stability Review:

It shows that scheduled mortgage repayments will lift to an all-time high share of household income by 2024.

However, this analysis was based on an OCR of 3.60 per cent, which is 0.50 basis points lower than the current level.

Therefore, the situation is now even worse with Australian mortgage holders soon needing to dedicate a record share of their income towards loan repayments.

How much worse will it get?

Forget the hoopla over the Fair Work Commission’s decision to award a 5.75 per cent wage rise to 20 per cent of the workforce, which in real terms represents a wage cut.

The main inflationary challenges facing the RBA come from two sources that are largely out of its control: rents and energy.

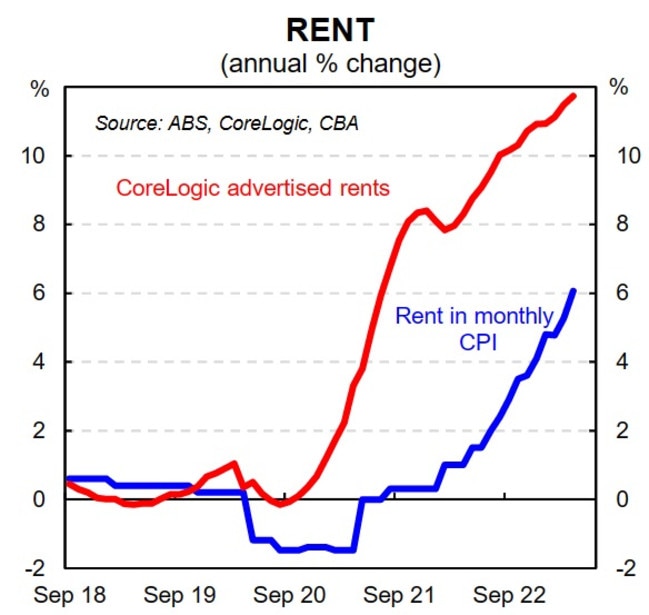

Residential rents are the single biggest component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), comprising around 6 per cent of the CPI basket.

At last week’s Senate Estimates hearing, Governor Lowe warned that that residential rental growth is expected to hit a three-decade high, which will continue to stoke inflation.

He noted that the rental measure used in the CPI is currently growing by around 6 per cent.

However, it is accelerating rapidly due to rock-bottom vacancy rates and will likely hit 10 per cent, which would be its highest rate since June 1989.

Lowe also warned that rent inflation would stay high for a long-time given Australia’s population is growing strongly, with rental demand far outpacing supply.

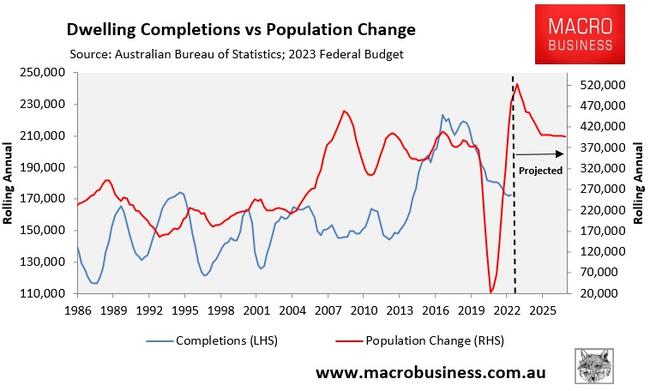

Perversely, the RBA’s aggressive interest rate hikes have contributed to the collapse new home construction, which will exacerbate rental shortages at a time of record immigration-driven population growth:

Accordingly, residential rents will continue to soar, which will place upward pressure on the CPI and force the RBA to keep rates higher for longer.

The other major inflationary pressure point is energy prices, which are stoking inflation right across the economy.

Despite Australia being the world’s largest exporter of LNG — “the Saudi Arabia of gas” — east coast consumers are currently paying the world’s highest gas prices due to our government’s failure to implement a domestic gas reservation scheme.

Gas is the key price setter for electricity, and on July 1, electricity prices along the east coast will rise by at least 25 per cent, which follows a roughly similar increase the previous year.

This energy inflation will add 1.8 per cent directly to the CPI over one year.

However, because energy costs feed into everything else, the inflation spillovers will be much higher because the costs will be passed on.

Energy costs could add anything up to 3.5 per cent to the CPI.

RBA attacks mismanaged immigration

At last week’s Senate Estimates hearing, Governor Lowe warned that the supply-side of the economy — business investment, infrastructure, housing and energy — was failing to keep pace with the record number of migrants arriving in Australia.

Last month’s federal budget projected an unprecedented 1.5 million net overseas migrants would arrive in Australia over the five years to 2026-27, with a record 400,000 arriving this financial year and 315,000 next.

Governor Lowe warned Senate Estimates that “the amount of capital that on average we have to work with is one of the drivers of productivity growth”.

“We do need to increase the capital stock in line with the number of people in the country and that requires high levels of investment. And if we don’t do that, then we’re going to struggle,” he said.

“If we’re going to have 2 per cent more people in the country [this year], we need 2 per cent more capital, and that requires investment by business and investment by government. Solving the housing problem, I think that’s the single biggest thing we could do. And then we’ve got to build the transportation infrastructure to support that.”

“Are there 2 per cent more houses? No,” warned Lowe.

The above statement was a veiled shot at the federal government, which has chosen to force-feed Australia with record migration without any plan to accommodate the extra people.

As a result, the amount of capital per worker is shrinking and rents are soaring, which is wrecking productivity growth and stoking inflation.

The RBA is being forced to hike interest rates, which is brutalising the one-third of households with mortgages, without addressing the underlying causes.

The answers to Australia’s inflation problem rests with the federal government: moderate immigration and fix the energy market.

Leith van Onselen is co-founder of MacroBusiness.com.au and Chief Economist at the MB Fund and MB Super. Leith has previously worked at the Australian Treasury, Victorian Treasury and Goldman Sachs.

Originally published as RBA caught between a rock and hard place on inflation