Fears for Australia’s mining towns as residents flee after the boom

THE mining downturn is devastating Australian towns, with entire populations are disappearing and leaving virtual ghost towns behind.

Mining

Don't miss out on the headlines from Mining. Followed categories will be added to My News.

OF ALL the miseries that residents in the Northern Territory town of Nhulunbuy have dealt with since the mining downturn, floods during the dry season is not one they expected.

The remote mining town in East Arnhem Land saw its population plummet from 4000 to about 2000 after Rio Tinto announced it would mothball its Gove alumina refinery, leaving a quarter of the town out of work.

Redundant workers and families fled en masse, leaving abandoned homes and struggling businesses in their wake.

Qantas even suspended flights on its Darwin-Nhulunbuy route last year.

But the water supply problem was an unexpected side-effect, former Nhulunbuy local Nicky Mayer told news.com.au.

“There are still a lot of empty houses, and because there isn’t the same volume of people using the water supply, the water pressure built up and the town ended up with a lot of burst water mains, and all around the (mining) site as well,” Mrs Mayer said.

“It created a completely different lot of issues. And I just saw on Facebook they’re now having to test the water, because the water supply has been infected with lead.”

Rio Tinto is still operating its smaller bauxite mining operation on the Gove Peninsula but a mass exodus of people after the curtailment of the alumina refinery has edged Nhulunbuy ever closer to becoming a virtual ghost town.

Australia is already littered with ghost towns: lifeless versions of once-thriving mining communities that withered and died as long ago as the Gold Rush.

Nicky Mayer is one of the long-time locals who made the tough decision to leave Nhulunbuy. The mum of three, who was Nhulunbuy’s local tennis coach, moved to Cairns with her youngest son in April last year. Like 1100 others, her husband had lost his job at the alumina refinery in 2013.

Mr Mayer is still in Nhulunbuy, having been contracted to work on Rio Tinto’s existing mining operation. Their oldest son, a third-generation mine worker, went to Curtis Island off the coast of Queensland in search of work.

While the family has been splintered, Mrs Mayer still thinks they’re the lucky ones.

“I saw people self-implode and get really stressed trying to find work elsewhere,” she said.

“My husband and I have a very close relationship, but there was a lot of husbands that had been affected by the closure of the refinery that weren't going home and talking about it with their wives and trying to deal with it themselves. Probably to the point that a lot of men had a nervous breakdown.”

Mrs Mayer regularly visits Nhulunbuy. But she says it’s a very different place to the thriving town she once knew.

“It’s very quiet, very dead,” she said. “It just doesn’t have the same buzz it used to have.

“I think those who chose to stay just take every day as it comes and try to keep normality as best they can. They’re still trying to keep the junior sports alive. The tennis centre hasn’t been able to replace me as a coach so the kids I worked with for the last 15 years have probably chosen to do different things now. There is a much smaller band of volunteers than there used to be.”

Many workers who lost their job at the refinery went to Western Australia and Queensland for work. Others decided to try their luck in Saudi Arabia.

The pubs and shops they used to pack have gone quiet and “for sale” signs line the once-bustling streets.

East Arnhem Real Estate agent Hannah Seaniger told news.com.au it was a buyer’s market in Nhulunbuy — there just weren’t any buyers.

“Prices have dropped dramatically,” she said. “A house that was worth $600,000 during the boom is really lucky to get in the high $300,000s now, and that’s a brick, good quality, three- or four-bedroom house with two bathrooms.

“The highest selling property since curtailment was $425,000 and I’ve had to sell properties for as low as $150,000.”

Ms Seaniger said existing residents were still worried about their jobs. The talk of the town at the moment is that Rio Tinto has just made another eight mine workers redundant.

“Things have taken a step back again,” she said. “We had a buyer who was extremely keen to buy and was ready to purchase but pulled out because it’s all so uncertain. Uncertainty has crept back into people’s minds.”

It’s a feeling too familiar in other parts of the country.

In central Queensland, the crashing price of coal in 2012 saw hundreds of jobs slashed in coal operations in the Bowen Basin, and one of towns it hit hardest was the once-flourishing mining hub of Emerald.

Like Nhulunbuy, Emerald saw a mass exodus of out-of-work miners. Those who remain are struggling to pay their rates, with the council owed almost $10 million by homeowners, according to The Australian.

Since 2012, rents for a three-bedroom house have plummeted from $800 to $250 a week. House prices have almost halved, with modern new homes now begging for buyers at just $250,000.

This is being felt across the Bowen Basin. The median house value in Dysart, near BHP Billiton’s now closed Norwich Park coalmine, has fallen 46 per cent in the past three years, from $414,788 to $325,962, according to RP Data figures obtained by Fairfax.

It’s worse in post-boom Moranbah, a coalmining town about 190km west of Mackay, where the median house value has dropped 66 per cent in the same period, from $404,006 to $251,933.

Even motel owners are hurting. In Emerald, they used to charge $300 a night in the height of the boom, but now struggle to fill rooms at a measly $89 a pop.

“It’s like a ghost town,” Emerald resident Blake Graham told The Australian.

“Heaps of my mates were working out here in the mines but they’ve had to move back to the Gold Coast and Brisbane.

“They’ve lost their jobs, sold their jetskis, new cars and all the other sh*t that you buy when you are 27 and earning $140,000 or more, and gone home to a labouring wage.”

Central Highlands Shire deputy mayor Gail Nixon told The Australian one upside of the mining downturn was that Emerald’s farmers could how find workers prepared to accept farmhand work at modest wages.

“We sometimes forget farming was here before mining and will be here after all the coal has gone,” she said.

“I think we need to put a bit more faith and assistance into our farmers because, once the mining boom is over, agriculture is what towns like Emerald will always have left.”

Emerald may have its farming fallback, but the challenge for other mining towns has been coping with the decline of the only industry their prosperity had been hinged on.

In a report released last year, Curtin University senior researcher Jemma Green warned that Western Australia’s lucrative Pilbara region needed to economically diversify or risk declining into “ghost town and tumbleweed” when activity around its lucrative iron ore and natural gas slowed.

“(The Pilbara) is a classic example of prosperous growth in a natural resources region, with the boom outstripping the ability to develop infrastructure to service it properly,” Ms Green said.

“History shows that this classic mine-and-boom phase is either followed by an evolution into multiple but related industries, or a decline into ghost town and tumble weed.”

Ms Green said careful forward planning could be the difference between evolution and decline for the Pilbara.

“This can unlock the region’s undeveloped potential for economic diversification and ensure its long-term economic viability,” she said.

“When a boom dries up what is often left is secondary and tertiary infrastructure. This can be enough to sustain a region, but only if such infrastructure has already been created.”

She said without diversifying, the Pilbara could meet the same fate as many other once-thriving boom towns.

Western Australia already has 87 ghost towns, and there are 75 in the rest of Australia combined.

In their heyday, most of these were mining towns, from Moliagul in Victoria, where the world’s largest gold nugget “Welcome Stranger” was discovered, to Cossack in Western Australia, the former hub of the nation’s pearling industry where just two residents now live.

Here are some of the country’s most notable ghost towns, where only a few neglected buildings or a lonely “welcome” sign bear evidence of their former resource-rich glory.

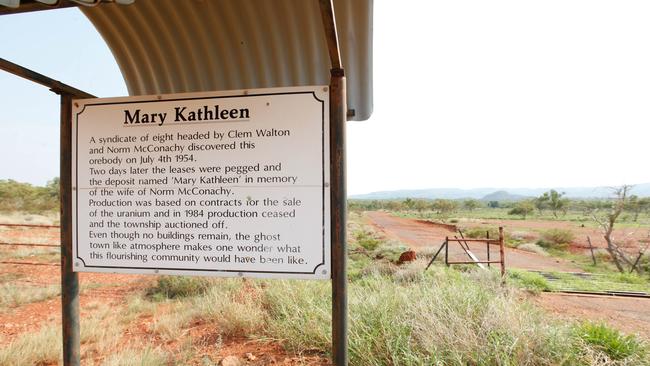

Mary Kathleen, QLD

Mary Kathleen, near Mount Isa, landed on the map in 1954 with the discovery of a significant uranium deposit — the biggest in Australia at the time. A mine was built and a thriving town was born, named after the late wife of one of the men who made the uranium discovery there. After extracting 4080 tonnes of uranium oxide in just six years, the mine was abandoned but eventually reopened, giving the town a second grab for glory. But the township and the mine were dismantled by the end of 1984, and only old streets were left behind.

Tarcoola, SA

Tarcoola is the town that time forgot. It used to be a booming goldmining town — it had its “eureka” moment in 1893 and produced 2.4 tonnes of gold during its heyday. The town’s population swelled during those prosperous years but gradually declined, and its last resident moved out last year. These days, the only action in Tarcoola is when train services such as The Ghan and the Indian Pacific rush through each week. A 1998 copy of the Adelaide Advertiser and a jar of International Roast coffee still sit in its long-abandoned police station.

Kiandra, NSW

Kiandra is an abandoned gold mining town that also happens to be the birthplace of skiing in Australia. Nestled high in the Snowy Mountains, the town was once home to about 25,000 people at the height of the gold rush, but a mass exodus ensued when the easy pickings dried up by the 1860s. It became popular as a skiing destination until the last resident left the town in 1974. Some ruins remain, including the old courthouse and cemetery tombstones, and there have been recent efforts to attract and accommodate tourists.

Wittenoom, WA

This is a ghost town rooted in infamy. Wittenoom first came to national attention when blue asbestos was discovered there in the 1930s. Nearly 150,000 tonnes of the deadly mineral was extracted until mining stopped in 1966. Hundreds of workers later died of asbestos-related diseases and a series of legal cases were brought against the operating company, founded by Lang Hancock. Three residents still live in the Pilbara town, which was degazetted in 2007 and technically doesn’t exist.

Silverton, NSW

This tiny town owes its former prosperity to its namesake. Silver was proclaimed there in 1875 and the town’s population swelled from a couple of hundred to 3000. But a depletion of resources, coupled with the discovery of even richer resources in nearby Broken Hill, sent the town into decline. Fewer than 50 people live in Silverton today, and even fewer buildings remain. But it has featured in plenty of films, such as Mission Impossible II (1999), Mad Max II (1981) and The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994).

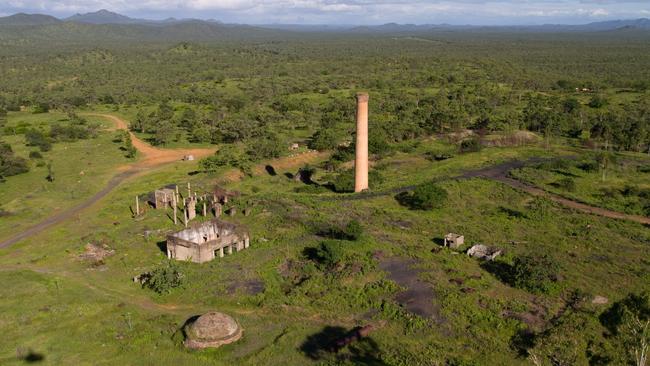

Mount Mulligan, QLD

A solitary chimney, a cemetery and a single occupied house is all that remains of the Mount Mulligan township, west of Cairns. It was a coalmining town and the scene of Queensland’s worst mining disaster in 1921, when underground explosions killed 75 workers, all Mount Mulligan locals. Mining continued until 1957 when a nearby hydro-electric scheme eliminated the need for coal. In 2006, the town had a population of just 55 people. There are now plans to turn the site into an exclusive resort.

Originally published as Fears for Australia’s mining towns as residents flee after the boom