APRA does heavy lifting for RBA on rates setting

APRA took an important first step to head off a risk from a red-hot property market that may help keep interest rates low.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Australia’s prudential regulator has taken an important first step to head off a build-up of risk in the nation’s red-hot property market that may help the Reserve Bank keep interest rates low for long enough to achieve a return to full employment and inflation consistent with its target.

In an earlier-than-expected move, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority told banks to lift the interest rate buffer they use when assessing home loans to at least 3 per cent above the loan product rate, up from the current 2.5 per cent commonly used by the banks and credit unions.

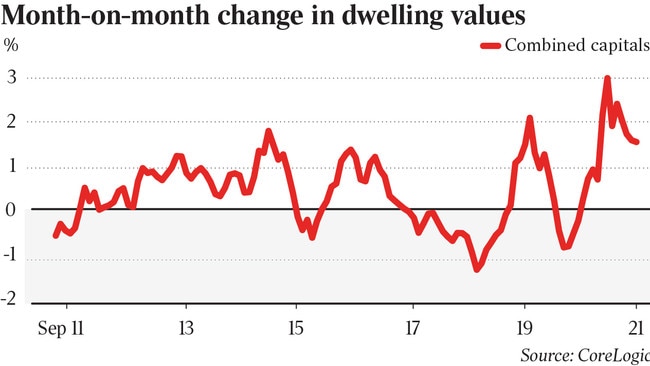

It came after house prices surged 20 per cent over the past year – the fastest pace since 1989 – and analysts predicted further strength in 2022 as the RBA argued that its inflation pre-condition for raising the cash rate from a current record-low target of 0.1 per cent “will not be met before 2024”.

While the RBA dialled up its warning on the importance of prudent home lending standards after its board meeting this week, APRA’s announcement on Wednesday came as a “hawkish surprise”.

Most thought owner-occupiers were driving the cycle and investor credit growth wasn’t a problem.

“On traditional criteria, there should not be a strong case for tightening lending standards, but clearly, something is different in policy makers’ thinking this time around,” said Credit Suisse macro strategist, Damien Boey.

He said it could be that policy makers are looking to pre-empt rather than react to an increase in investor lending, or they see risks in the owner-occupier segment that they have not before.

“Either way, macroprudential tightening will end up restraining the housing market by locking out those who were already locked out by poor affordability.”

He said credit conditions as of August were already at levels historically consistent with 17 per cent fall in home loan approvals as a share of credit, and that as APRA tightening kicks in, credit conditions will deteriorate, consistent with more weakness in loan approvals.

“This will likely compound the effects of lockdowns and the CFR’s seeking of assurances from the banks from a few months ago regarding the appropriateness of their lending standards,” he said.

In light of the fact that Australia has so far followed the same path as New Zealand – which hiked interest rates from a record low on Wednesday after imposing macroprudential controls and ending its own bond buying program – analysts were pondering whether pre-emptive macroprudential tightening by APRA could be “alternative” to rate hikes by the RBA.

Credit Suisse’s Mr Boey noted that while APRA drives the macroprudential agenda more so than the RBA, there is an interaction between the different arms of monetary policy.

“The RBA is on record as saying that monetary policy, construed narrowly as interest rates setting, is not an appropriate lever for influencing house prices,” he said.

“In other words, the Bank does not want to ever have to raise rates to contain or respond to house price inflation, and in this context, macroprudential tightening from APRA temporarily fills a gap.”

But this is not to say that there are no rate implications of macroprudential tightening.

If APRA were to “overdo” lending standards enough to “bring down house prices”, the risk in terms of RBA policy would be that interest rates and bond yields will “have to stay low or even fall.”

“On the flipside, if APRA is successful in containing leverage build-up, potentially it can help the RBA to avoid the pitfalls of a sharply falling neutral rate,” Mr Boey added.

“Further, if macroprudential regulation is really APRA tightening on behalf of the RBA because the RBA does not want to break its forward guidance or go with more hawkish central banks globally, then arguably tightening is a sign of good growth, thematically consistent with higher rates.”

But despite the prospect of easing coronavirus restrictions allowing stronger migration that supports housing demand, Mr Boey noted that there’s also a lot of new housing supply coming on and that in the shorter term, a fall in loan approvals will have a negative impact on house prices.

He also thinks that global investors and central banks are struggling with the prospect of bond yields and rates rising, because of their potentially negative and disproportionate impact on asset prices which have been taken to extremes precisely because of low yields and rates during the pandemic.

“Globally there is uncertainty, no doubt there must be uncertainty in Australia too,” he said.

“In Australia’s case, much of the recent search for yield has already manifested in strong house price inflation and mortgage credit growth, constraining where the RBA can ultimately set rates.

In this regard, we agree with the motivation for doing something about financial stability risks – but arguably, the horse has already bolted, and now may be a little too late to be acting.”

Originally published as APRA does heavy lifting for RBA on rates setting