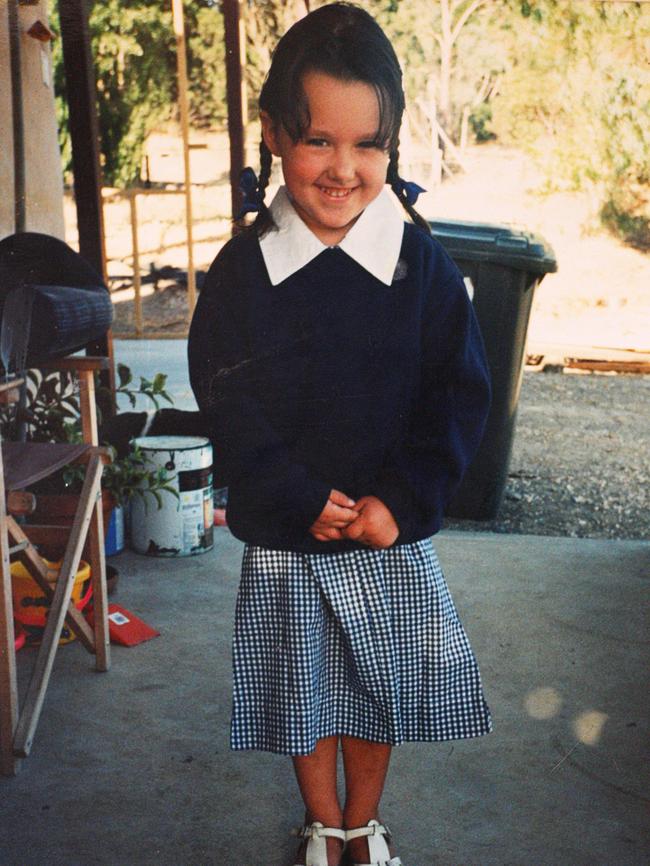

HER name and image are now synonymous with internet safety — and with encouraging children and teenagers to be responsible while having fun online.

But that was not always the way the public saw murdered South Australian schoolgirl Carly Ryan.

In the dark days immediately after the 15-year-old’s body washed up on the shores of a popular tourist beach, ignorance and misunderstanding turned her into a pariah.

No one really understood, in 2007, how dangerous the internet could be.

For many, it was that thing young people used, or a cheap way to buy items from overseas — or an easy gateway to pornography and titillation.

“Internet predator” was not a term in 2007, and nor was “cyberstalking”.

And so when Carly was murdered, the age-old misogynist culture of victim-blaming kicked into overdrive.

People were only too willing to blame a so-called “goth”, an “emo”, for her own demise at the hands of a perverted older man.

Carly’s purported connection to one of the early internet’s most infamous websites — vampirefreaks.com — added fuel to the character assassination.

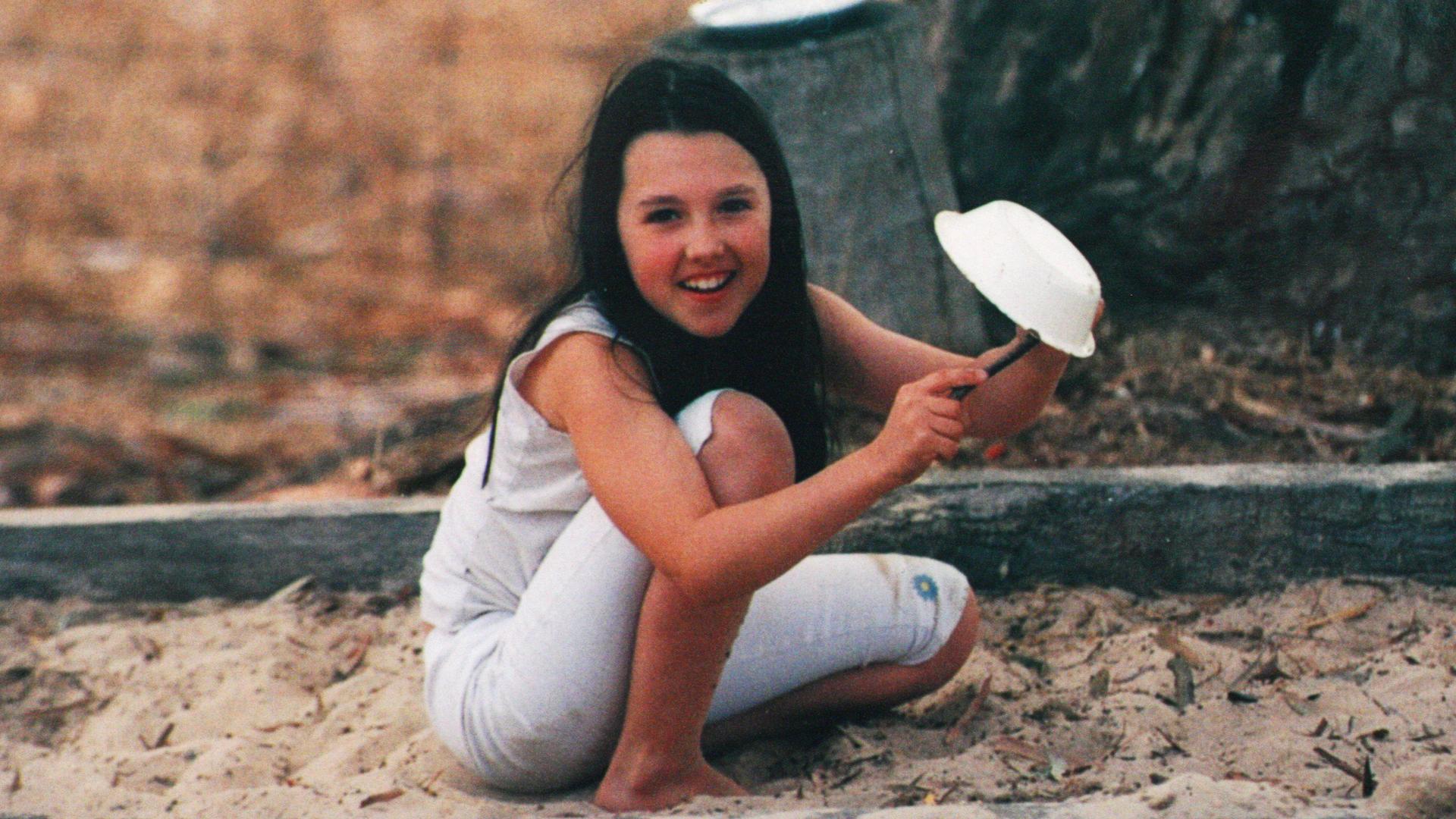

In truth, the Adelaide Hills teenager was far more than “that girl from the vampire website’’ — fun-loving and unfailingly friendly, Carly was anything but a morose, depressed emo.

Although she liked the subculture’s clothing and music, she was more likely to wrap you up in a hug than turn away from you with a sneer.

Yet it was that accepting nature — and a near-death experience — that left Carly vulnerable to the advances of a foul, deviant predator.

Her death was the first of its kind not only in Australia, but in the world — the first time an internet predator reached out and killed his victim.

But at its core, the murder of Carly Ryan came out of a 15-year-old girl’s search for love.

WHO WAS CARLY RYAN?

Born on January 31, 1992, Carly lived with her mother, Sonya, in Stirling, a quiet hillside suburb just 20 minutes from the Adelaide CBD.

“We had a close relationship, very open, and we got along very well — almost a friend-like relationship,’’ Ms Ryan said during the trial.

Carly’s innocence was shaken, however, by a series of negative peer experiences.

Having made the decision to walk away from those friendships, the internet became her outlet — particularly social networking website MySpace – and she made new friends.

Contrary to early reports, Carly was never a member of the controversial vampirefreaks.com site.

Her connection to it came through some of her new friends who, in turn, introduced her to the love of her life.

Brandon Kane was a 20-year-old, Texas-born, Victorian-raised emo, who played guitar and thought Carly was “hot’’.

For a 14-year-old going through the typical adolescent search for identity, he was a dream come true.

“She said Brandon was really cute and that she really liked him,’’ Ms Ryan said.

“She was like a giddy teenager in love — really happy, really light and really excited.’’

Carly was not the first South Australian girl to catch Brandon’s eye — he had pursued her best friend, Ashleigh Humphreys, a year earlier.

“We would talk about normal stuff, like what we did during the day, and then he would bring up sex stuff,’’ Ashleigh said in 2009.

“I wouldn’t talk like that and I didn’t go along with it … that’s when he said I was boring.”

Brandon’s attention, she said, then turned to a photo she had posted of Carly.

“He said she was hot and asked for her email address … not long after that, they started talking.”

Brandon’s tastes ran to the risque.

“My sister kissed Carly and I kissed Carly … my sister’s kiss was videotaped with a camera,’’ Ashleigh said.

“It might have been posted on a website, I don’t know … Carly did this because she liked Brandon and wanted to make him happy.’’

Carly also began to communicate with Brandon’s “adopted father’’, Shane, and their chats made her friends even more uncomfortable.

Shane would speak to Carly and her friends over the phone, asking if they were bisexual and liked kissing girls.

Over time, Ms Ryan noticed her daughter’s website profiles had changed dramatically.

“There were images I was taken aback by … some dark art, really risque, dark and sexual images,’’ Ms Ryan said.

“With the photo of Carly, I couldn’t see her face … she had taken a three-part image of her chest, waist and legs wearing fishnet stockings and a bra.’’

With her 15th birthday party planned for January 26, 2007, Carly invited Brandon to attend — an invitation Ashleigh urged her to rescind.

“In January 2007, Carly and I weren’t getting along very well,’’ she said.

“We’d had a fight because she wanted Brandon to come down here but, because she didn’t know him and he was older, I thought it was silly.

“That was the last time I saw her.”

Brandon declined Carly’s invitation, saying he would be overseas, and offered to have Shane go in his place.

Ms Ryan was hesitant to agree to that.

“I said to Carly that I didn’t know this person and I wasn’t sure it was a good idea,’’ she said.

“Carly tried to assure me he was Brandon’s dad, a security guard and that we would get along well.’’

The man who arrived at the Ryan house in January 2007 was not Shane, the SAS commando who had worked as a bodyguard for goth rocker Marilyn Manson.

He was, in truth, Garry Francis Newman — a 50-year-old, divorced father of three who lived with his mother.

SECRET ALIASES

“Shane’’ was but one of 200 fake identities operated by Newman, who used web design jobs to cover up his plethora of constructs.

Others ranged from the tame “kuruptkoala’’ to the more risque, and his computer hard drives were filled with vampire trivia and child pornography.

“I may not be a kid anymore, but I tend to act much younger than I am,’’ he wrote on his website.

“I do go for women somewhat younger than me usually … someone sexually adventurous.’’

Newman had pursued a 14-year-old girl in the United States in 2002 and 2003 referring to her, in online exchanges, as his “princess’’ and his “wife’’.

He had also communicated with a 14-year-old girl in Singapore, while using the alias “Nash’’ — but she did not attend their planned meeting, leaving him in a rage.

Newman told his online friends the girl “would pay’’ for standing him up, saying he would use “a young guy’’ to lure her out of her home.

He told another friend she would end up “looking like that packaged meat you get at Safeway’’.

In January 2007, Newman — under the guise of “Shane” — travelled to Adelaide to consummate his sexual obsession with Carly.

Confident of his success, he told his co-workers he was starting a new life in Adelaide.

He was convinced the girl would accept him in place of the Brandon fantasy, but Newman received a less-than-warm reception on his arrival.

“He was stocky with thinning hair, had crooked teeth and walked hunched over like an ape,’’ Ms Ryan said.

“Carly told me she thought he was gross.’’

Undaunted, Newman spent time with Carly and her friend Rhiannon Lea Andrews-Healey.

“Shane’ tried to convince me and Carly to kiss while he watched,” she said in 2009.

“Carly then went to try and kiss me but I pulled away … she got angry and walked off.

“Shane said to me ‘maybe she wouldn’t have walked off if you had given her what she wanted’.”

Newman took Carly to Rundle Mall, Adelaide’s main shopping precinct, and bought her $400 worth of corsets, accessories and dress-up costumes.

While she tried them on, he peered over the change room doors to watch.

At a party he became jealous, saying “Brandon is on the phone’’ if she spoke to other boys.

Late that night he slipped into her bed, whispering “I love you’’ and “I’ll never let anything happen to you’’.

Discovering this was too much for Ms Ryan.

“I was shocked … I didn’t really know what to do,’’ she said.

“I knew that Shane had quite a hold over Carly because of Brandon and I was trying to think

what was the best thing to do at the time.”

She demanded Newman leave her house and stay away from her daughter.

“The next day, I asked her if he had touched her sexually in any way,” she said.

Her daughter eventually revealed Shane had unbuckled her pants, lifted up her top and “felt her up”.

“Carly wanted me to talk things through with Shane because he was Brandon’s dad,’’ Ms Ryan recalled.

“I said I didn’t care.”

Ms Ryan sent an email to “Shane”, telling him to stay away or she would notify police about the incident.

Upon his return to Victoria, Newman retaliated with vile, false accusations.

“Bitch, that email was full of lies and hearsay and I’m disgusted that someone of reasonable intelligence could believe such crap,’’ he wrote.

“The things you called me were totally defaming … I sincerely hope you have insurance against lawsuits, you will need it.

“I will go into court as a decorated SAS officer, while you will go in as a child-abusing bitch.”

A PREDATOR SPURNED

Newman wanted revenge, but there were obstacles in the way.

The first — and perhaps most insurmountable — was Ms Ryan, who was closely monitoring Carly’s movements and communications.

Newman’s other obstacle was Carly herself, who had no interest in seeing “the gorilla man” again — and was ever more insistent in her desire to meet Brandon face-to-face.

If he was to lure her away from safety, Newman needed a real-life Brandon.

“At first he said he wanted to go on a holiday, back to Adelaide, with me,” Newman’s eldest son recalled.

“Later, he said he wanted to ‘fix up’ Carly and said other things that indicated he wanted to harm her.

“He wanted me to help him while he was there, to help him kill her … I didn’t know what to do … I was stumped.”

Shocked and upset, the young man moved out of the house but left behind a letter.

“The letter was pretty abusive … I was hoping I might persuade my father about wanting to kill her,” he said.

With his son refusing any part in the vicious scheme, Newman turned to a boy he barely knew.

That boy, then aged 17, had spent most of his life in foster care and had known Newman for less than a month when he was invited to go to Adelaide.

In Newman’s mind, that made the boy the perfect person to portray Brandon in real life.

He went almost immediately online, donning the Brandon construct once again, and asked Carly to meet him on February 19, 2007.

Brandon urged Carly to keep the meeting secret from her mother, explaining Shane was “my ride” and his presence was therefore essential to them finally being together.

Carly, the adolescent girl searching for her identity, did what so many other teens before her had done — she lied to her mother.

She concocted a story of her own, telling Ms Ryan she was going to spend the night at a friend’s place, before hugging her goodbye.

“Carly hugged me about four times, turned the corner of the house, said ‘love you’ and walked out the back of the property,” she said.

In the years that followed, Ms Ryan would often speak of that final hug — how long it was, how strong it was, how passionately Carly gripped her.

She would wonder whether, on some deeper level, Carly knew just how much she was about to betray her mother’s trust by sneaking out.

But no one could ever have known what was about to happen.

THE TRAGIC DISCOVERY

On February 20, 2007, Kim Griffin began her day as she always did — with a leisurely stroll and bracing swim along Horseshoe Bay, more than 80km south of Stirling.

“When I got to the water’s edge I noticed a body, laying facedown, and I called for

help,’’ Ms Griffin said in 2009.

“I was alone on the beach, I just sang out ‘help’ but nobody responded.”

The body was that of Carly Ryan.

Desperate, Ms Griffin left the body and ran to a nearby car park where she found fisherman Ian Slade.

“I asked him to go up to the phone box and call 000 but, before that, if he could help me get her out of the water,’’ she said.

Mr Slade checked Miss Ryan for a pulse, to no avail.

“I said to Ms Griffin, ‘I’m sorry, I can’t help her any more’,” he said.

Forensic pathologists would conclude Carly had been attacked from behind, pushed face-first into the sand and smothered.

However, that would only have rendered her unconscious — meaning the teenager was alive when Newman threw her into the water, leaving her to drown.

The experts concluded she may have died just half an hour before Ms Griffin found her.

“She was covered with sand from head to foot,” SA Police Sergeant John Woods, who examined Carly’s body at the scene, would later recall.

“There was blood present in the cuts, and abrasions to her face.”

His colleague, Sergeant Stephen Tully said Carly had been dressed in a black tracksuit, a red and black bra, a leopard-print singlet, suspenders and fishnet stockings.

“The tracksuit pants were inside-out, the bra was worn correctly at the front, but at the rear it was a doubleclasp, and only the lower clasp was attached,” he said.

Though the officers did not know it at the time, the tangled nature of Carly’s clothing was a vital clue.

As they investigated, Newman and the boy returned to Victoria and met up with his eldest son.

“My father showed me his knuckles and asked, ‘Do these look bruised to you?’,’’ the eldest son would recall.

“He told me that he had punched Carly Ryan in the face, that he had killed her, that he had ‘done the job’.

“He said he had punched her in the face, pushed her face into the sand and, after that, he had thrown her into the water.’’

As Newman boasted, SA Police began to piece together the truth about Brandon Kane.

Horseshoe Bay was not far from Victor Harbor, one of SA’s most popular seaside tourist towns, and Carly Ryan was all over its CCTV footage.

Police recovered images of her, Newman and the boy outside the Crown Hotel, at a fish and chip shop, and eating at the local Subway outlet.

One of the fish and chip shop’s workers remembered Newman asking for “a good place to have a drink”, and suggesting Horseshoe Bay.

A cashier at the Victor Harbor supermarket said Newman had asked him the same question, and he had given the same answer — while selling the paedophile a packet of cigarettes.

Other witnesses soon came forward, helping police track the trio’s movements through the town.

Several of them would later pick the boy out of a photographic line-up, but none were able to positively identify Newman.

Every witness could identify Carly, describing her as either “gothic” or “emo-looking”.

A key breakthrough came thanks to two people who had been walking along the cliffs above Lady Bay, a small inlet whose tides and current fed into Horseshoe Bay.

They told police they had seen two men — one of whom had a torch — and a woman “who had a gothic look” sitting “down by the water”.

The pair had also taken note of a powder-blue car parked on the cliffs, bearing Victorian licence plates, with what looked like a security guard’s pass on the passenger side dashboard.

From there, it was a simple matter of tracing the plate to its owner.

Detectives found the car outside the house Newman shared with his mother and, on the passenger side dashboard, they saw the security guard pass.

Seeing that false pass, a relic of the “Shane” identity’s supposed time guarding celebrities, police knew they had their man.

Fittingly, they arrested Newman at his computer — perhaps saving another life in the process.

At the very moment he was apprehended, Newman was logged in as Brandon and chatting with a 14-year-old girl in Western Australia — his next target.

TARGETS

Detectives soon rounded up the boy, charged he and Newman with murder and extradited them to South Australia, where a court banned all publication of their identities.

Anonymous yet again, Newman immediately turned on his co-accused, insisting the younger man was the creator and sole operator of the Brandon identity.

“Just because (the boy) is af**kingliar, I won’t be able to be with you again,” he told his son in a phone call recorded by the Adelaide Remand Centre.

“I’m not saying (the boy) didn’t have any involvement — but I didn’t, truly.

“I’m telling you, mate, I did nothing to Carly … you’ve got to believe that, because I didn’t do anything to her.

“If the cops try and make you a deal, tell them to fuck off … I’m being stitched up for the murder and dragged into the shit by the media.”

He would try to blame the boy throughout their three years in custody, all the while talking himself up to fellow inmates.

Bragging of his prowess, Newman quizzed his cell mates as to whether they “had ever tried to put clothes on a dead weight” — linking him to Carly’s tangled clothing.

The public knew none of this, having only been told Carly’s death was linked to her internet use.

The unprecedented nature of the crime made it a media sensation and, unforgivably, an innocent girl’s name was quickly dragged through the mud.

Media, mainstream and social alike, was quick to adopt the easy narratives of “vampire girl gone wrong” and “emo teen’s fatal tryst with older man”.

Bound by suppression orders and the rules of a fair trial, Ms Ryan was able to only suffer in silence as the truth of her daughter was obscured by ignorance and misunderstanding.

So high profile was the case that the state’s top prosecutor, Stephen Pallaras QC, vowed to handle it personally.

Not known, at that time, for regular courtroom appearances, SA’s Director of Public Prosecutions announced he had “taken conduct” of the matter.

However, just weeks before the trial was slated to begin, veteran prosecutor Tim Preston appeared before the Supreme Court and said he would be conducting the case.

Mr Pallaras, it transpired, had double-booked himself — instead of the courtroom, he was bound for Kiev, in the Ukraine, for an annual prosecutors conference.

His broken vow brought the case back into the headlines as, on October 20, 2009 — 965 days after Carly drowned — Newman and the boy finally stood trial.

But before proceedings began, Supreme Court Justice Trish Kelly declared all evidence of Newman’s pursuit of other teenagers to be inadmissable and prejudicial.

A common legal ruling, the act kept the jury focused on evidence relating directly to Carly — even as Newman changed his tune.

TRIAL OF A LIAR

He took the witness box in January 2010, insisting neither he nor the boy were murderers — but offering to plead guilty to the lesser crime of manslaughter.

Newman described his interest in the teenager as purely platonic.

“Carly and I would talk about music, movies, her problems at home … I became like a stepdad to her,’’ Newman said, appearing to fight back tears.

“Did I have a romantic or sexual interest in her? Oh, no way, not at all — I’m actually asexual, so I have a low interest in sex as a whole.

“(The boy) and Carly were having an internet relationship … I did not kill her, and neither did he.”

Newman told jurors he had never used the name Brandon Kane, but admitted he had posed as “Shane”.

He said he had never touched Carly inappropriately or sexually, but conceded an obsession with social networking websites.

Newman blamed his 200 accounts on a years-long struggle with bipolar and obsessive compulsive disorders that also caused him to “go off for no reason at stupid things”.

He was, he assured the jury, now medicated for his problems and had become “a lot better person than I used to be”.

“Carly knew me as Shane and we were very close friends … I know there was quite a bit of an age difference but I’ve always had a young outlook,” he said.

“I act like I’m in my 20s and I’ve always related well to young people … It’s not something I set out to do, it’s just the way I am.”

He admitted creating a MySpace web page for the Brandon identity under instructions from a friend in California.

The site listed Brandon’s favourite TV shows as The O.C. and Alias — which were, not coincidentally, Newman’s must-watch programs.

“Those are favourite shows of mine, but also of other people … I’m not the only person to have DVDs of either show,” he protested.

Unsurprisingly, Newman admitted he had taken Carly and the boy to Port Elliot — the CCTV evidence was inarguable — but he had an excuse for that as well.

The teenagers, he said, were attending a party and, afterwards, he and the boy had left her alone on the beach.

“This is where I’ve got a bit of a story for you,” he told the jury, his tone almost conspiratorial.

“She was fine but pretty stoned, though.

“We found out three days after we got back that she had died, and I knew I would be spoken to by the police — but I didn’t do a runner, did I?

“I had nothing to cover up.”

They were the words Mr Preston and barrister Bill Boucaut, who represented the boy, had been waiting to hear.

The pair spent the next 6 ½ gruelling days dissecting Newman’s bizarre and contradictory evidence which, they agreed, was no more than “elaborate lies”.

In heated exchanges, Newman argued it was normal to use fake names while communicating online.

“I did not pass myself off as ‘Brandon’, never ever … you don’t know who’s who on the net … it’s always been a good idea not to give out your private details,” he said.

“I’ve explained to you that a lot of people — and I mean a lot of people — use different names on the internet.

“Experts recommend it for security, police recommend it so there’s less identity theft, so a lot of people use bogus names.

“You’re making it seem like it’s some big, horrible thing but it’s the smart way to be.”

Newman was, he explained, on a crusade to prove life on the internet was “not so crash-hot”.

“My 200 identities were research (for) a book about the internet,’’ he said.

“It would be about how websites can be manipulated by people, including myself.”

He said his asexuality was the result of a childhood kidnap-and-rape ordeal which had left him “with a low libido’’.

“It’s one of the reasons, I’m told, I don’t have normal sexual urges and little to no interest in sex,” he said.

“It’s not something I like to admit, it’s very personal to me.

“Carly was attractive in a way, but I really didn’t look at it like that … not sexually at all.”

Newman admitted that, as Shane, he had once told Carly he was going to “take the virginity” of a 19-year-old he met online, but said that was only “an inappropriate joke”.

He claimed that 19-year-old — who was “probably way too young for me” — had become “obsessed” with him.

When Newman told jurors that Carly’s death had “broken my heart”, Mr Boucaut pounced.

“You found out that your ‘daughter’ was dead and did not think to call her mother to say ‘this is just appalling, tragic news’?” he asked.

“I do not believe your big, fat lies.”

Newman went on the offensive, insisting he did not have Ms Ryan’s phone number and had called CrimeStoppers with information about the case — a demonstrably false claim.

“You’re trying to make me seem sick and perverted,’’ Newman whined.

“You’re trying to make out like I’m some sort of predator … a sicko predator.

“I was irritated by the whole kissing thing, absolutely.”

Asked why he had tried to plead guilty to manslaughter, Newman said he acted out of nobility.

“The evidence was looking like one of us would be convicted … I was going to be the sacrificial lamb and I was going to plead guilty so the boy could go home,” he said.

“I was worried about him being in custody for so long for something he did not do, I was prepared to plead guilty to something I had not done because I wanted him home.

“I thought wrong, didn’t I? It was misguided, wasn’t it? I’m sorry if I went the wrong way about it.”

But for all his dodging and weaving on the witness stand, Newman was even more evasive when the jury was not present in court.

On two occasions his counsel, Nick Vadasz, sought to withdraw from the case due to “irreconcilable differences’’ with his client.

The court heard Newman had written to other lawyers, seeking their opinions about Mr Vadasz.

The younger man, by contrast, did not take the stand.

Mr Boucaut told the jury there was nothing to connect his client to the murder, saying the evidence was “one-way traffic’’ pointing to Newman.

As the end of the trial drew near, Newman’s condition deteriorated markedly — he sat shaking in the dock and his facial hair became unruly.

It emerged he was being held under suicide watch — and so had been denied the use of razors — following a seizure in his cell brought on by being called a liar.

VERDICTS AND UNMASKINGS

The jury deliberated for 10 1/2 hours over two days, pausing only to ask for Justice Kelly’s assistance.

Jurors wanted to know if they could find one man guilty of murder and the other guilty of manslaughter.

Upon hearing that question, the younger man burst into tears.

“The short and simple answer to that is ‘yes’,’’ Justice Kelly said.

She further explained to the jury they would need to be satisfied of many factors were they to find the boy guilty of either crime.

For him to be guilty of murder, she said, they had to be sure he either participated in the plot to kill Carly or encouraged the crime.

To be guilty of manslaughter, the boy must have participated in a plot to do harm to Carly — resulting in her death — or encouraged Newman to harm her in a fatal way.

The jury could not find the boy guilty of the lesser offence of assisting an offender, because prosecutors had never charged him with that crime.

When, at 4.30pm on a Thursday, the jury found him guilty of murder, Newman showed no reaction.

The boy, however, was visibly relieved at news of his acquittal — mouthing “thank you” to jurors — and arrangements were made for him to return to Victoria that night.

He left court flanked by family members and surrounded by a media scrum.

“He never did anything, he’s a good boy … Newman pulled him into it, he shouldn’t have been there,” the boy’s grandmother told reporters.

“He’s very sorry for all that’s gone on … he’s a good boy, you know.’’

The boy had done more than secure his own freedom — he had done Newman a favour.

Thanks to the onerous, draconian complexities of South Australian law, his acquittal meant the suppression order upon the duo’s identities could not be lifted.

Convinced the public had a right to see Carly’s killer — and determined to forever shatter Newman’s anonymity — The Advertiser fought to have the order revoked.

In the end, it was forced to strike a devil’s bargain with the Supreme Court.

Justice Kelly was required by law to protect the boy’s identity — after all he had, according to the jury, committed no crime.

Unmasking Newman meant all-but excising the boy from the story, reducing his presence in coverage to the barest of mentions.

In the end the deal was struck and, as he began his minimum 29-year prison term on March 1, 2010, Newman’s simian features were revealed to the world.

The boy’s identity, meanwhile, was forever consigned to the vault of SA state secrets.

That meant The Advertiser could not link him, years later, to a series of grotesque sexual offending committed elsewhere.

Nor could it report on the circumstances of those crimes — each of which, horrifyingly, mirrored the events preceding Carly’s death — nor his ultimate punishment.

Mr Pallaras, who missed much of the trial while in the Ukraine, also chose to keep silent.

He refused to be interviewed about his broken vow which was, for many years, a sore spot between Mr Pallaras — who felt he had been misrepresented — and the media.

That dispute was eventually resolved but, far more importantly, Mr Pallaras’ standing with Ms Ryan, and her happiness with him and his office, was unaffected.

A MOTHER’S CRUSADE

Ms Ryan, by her own admission, was left with two choices.

She could either buckle under the crushing grief of having lost her daughter, or allow their unique “love connection” to fuel a crusade.

She chose the latter and, in January 2010, announced the creation of the non-profit Carly Ryan Foundation for internet safety.

“A future without Carly is just too terrifying to imagine, like someone switched off the light that she brought into our lives,” she told The Advertiser.

“You can either fall into that blackness and completely give up or you step into the light and do what you can — and that’s trying to help others.

“What else is there? It’s pretty much the only choice I have.

“If I have to be here without Carly, then my aim is to help create awareness.”

Carly, she said, would have been “utterly horrified” to learn the depths of Newman’s deception — meaning countless other teenagers and parents were unprepared for similar monsters.

“A lot of people believe whatever they read on the internet is true, especially children … they believe what they see, but there is just so much deception out there and on so many levels.

“All it takes is for a trusting teen to believe what a predator is saying to them and their safety is instantly taken out of their hands.

“Carly was a very compassionate young lady and she would be wanting all of us to do whatever we can to stop this happening again in the future to another young girl.”

Over the next decade, Ms Ryan gave her all to the cause.

The Foundation pioneered the rollout of a child/parent safety app, Thread, allowing for instantaneous communication, tracking and panic alerts.

She visited schools to teach students how to protect themselves and spoke to their parents, emphasising the role they must play in their children’s lives.

Tragically, many of those children would approach Ms Ryan and reveal they had already been stalked by a predator — she counselled them, and connected them with police investigators.

Ms Ryan spread her message everywhere, from high-volume music festivals to United Nations symposiums, across Australia and around the world.

Three years after the trial, Ms Ryan was named South Australian of the Year and sat on Federal Government consultancy groups — but she was not done.

Her goal, all along, had been the creation of “Carly’s Law”, a new piece of legislation that made it illegal to lie to a child online.

On June 15, 2017, Ms Ryan stood in Parliament House in Canberra as “Carly’s Law” became a reality — carrying with it a 10-year maximum prison term for offenders.

The first arrest under the law was made just a few weeks later, prompting law enforcement agencies overseas to investigate adopting the legislation.

On July 3, 2018, a state-based version of Carly’s Law passed both Houses of the South Australian Parliament.

“My beautiful daughter’s legacy now enshrined in legislation to protect other innocent children from harm,” Ms Ryan said.

Carly died in a time of ignorance, before the public truly understood the reach, power and potential dangers of the internet.

Hers was the world’s first truly 21st century murder — but her memory, and the law named for her, will forever protect Australia’s children from monsters like Garry Francis Newman.

(Produced by Paul Purcell).

‘Massive step’: Critical CCTV could unlock clues in Rachelle’s cold case

CCTV footage from the night Rachelle Childs was murdered will be re-examined, with her family hoping it will unearth vital clues to help find her killer. Listen to the podcast.

‘Fingers cut off’: Sickening bikie twist in Rachelle’s murder

Rachelle Childs ‘partied with bikies who killed her and severed her fingers’. This was one rumour peddled following her gruesome murder. Listen to the podcast and watch the video.