The rise, lies and demise of crooked police inspector Barry Moyse

Over the course of the ‘80s, Barry Moyse turned from the face of the war on drugs into a claimed scalp. After staunchly opposing an investigation into police corruption, he was eventually and ironically exposed as one of the worst dealers himself.

True Crime

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Greed was good, the MTV generation was told to “just say no” to drugs, while pious millionaire TV evangelists took hypocrisy to a grand scale.

One South Australian who encapsulated the contradictions of the 1980s was Barry Malcolm Moyse, who went from being the public face of the war on drugs as head of the drug squad to being behind bars by decade’s end, disgraced as a drug dealer.

In the first of a two-part True Crime Australia report, Andrew Dowdell charts Moyse’s rise, and the fateful agreement that proved his downfall.

Whispers became quiet rumours among Adelaide’s drug scene but when The Advertiser published claims that crooked senior police were colluding with drug dealers, all Hell broke loose.

The Advertiser’s report in August 1981 culminated a six-month investigation, during which lawyers, drug dealers, users and honest cops echoed a familiar narrative.

According to the sources, a small but rotten core of officers were deeply involved with Italian cannabis syndicates and exploited their hold over street dealers to line their own pockets.

At least eight senior policemen, including a Commissioned officer, were accused of a litany of crimes and corruption — sparking a furious and indignant police response that would later prove laden with irony.

The rogue cops allegedly accepted bribes for overlooking crimes, framed dealers too slippery to catch lawfully, hoarded wads of cash, re-sold seized drugs and helpfully tipped off their “favoured” dealers about imminent drug raids.

Other sinister claims included late-night break-ins at offices of criminal lawyers, stolen files, arson attacks and a caryard being blasted with shotgun pellets late at night.

Some police allegedly had offered cash bounties to criminals in exchange for their help to fabricate evidence against dealers who’d fallen out of favour.

Lawyers and known criminals said nothing less than a Royal Commission would convince them to air their claims publicly.

They said any government inquiry would be pointless, and testifying would be foolish, if not suicidal.

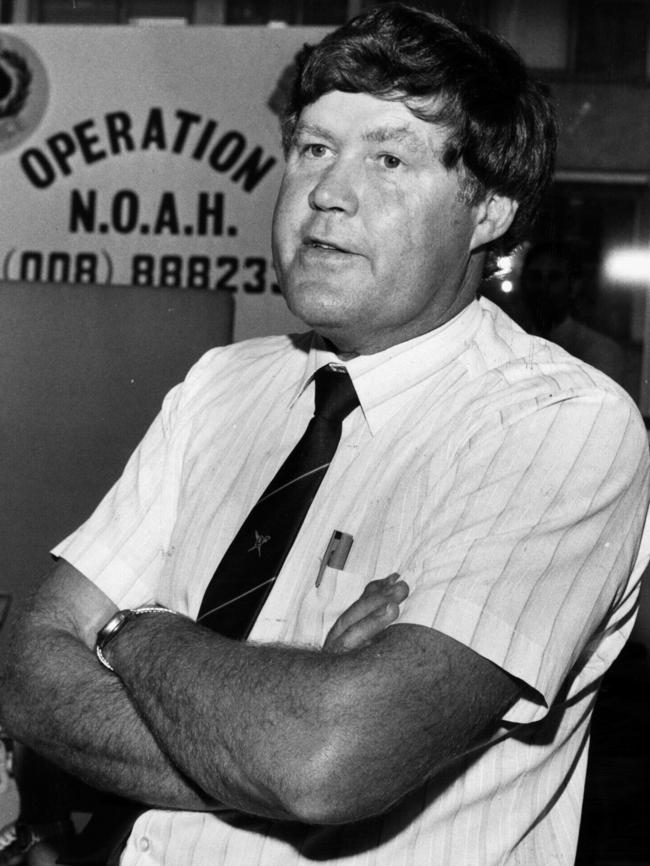

It marked a new battleground in state Parliament and invoked a furious public retort from SA Police Association president and rising SAPOL star, Inspector Barry Moyse.

An incredulous Moyse said a Royal Commission would play into the hands of “drug dealers and peddlers who are pushing drugs to the youth of Australia for their own financial gain”.

“We ask how these criminals can dictate to society the terms of any inquiry … these persons are trying to discredit police,” he said.

“The terms they require are completely unreasonable (and) Royal Commissions have a history of dismal failure in Australia.”

Insisting SA had “no place for bent officers”, Inspector Moyse scoffed at suggestions police were trying to “dodge any issues or protect officers”.

The colourful tirade would prove to be a master class in rank hypocrisy, when Moyse was later unmasked as a bent and arrogant cop and drug dealer of the worst kind.

The furore also claimed lives. In October 1981, the body of a police inspector and former drug squad detective was found on Pebble Beach near Myponga.

Ruled a suicide, the Inspector was found next to a .22 calibre rifle and handwritten notes addressed to his family and senior police, who did not reveal the contents.

The Labor opposition, already on the attack over the parlous state of SA prisons, used the affair as a political wedge.

It tried to paint the Liberal government as the party of the establishment, unwilling to challenge the unspoken authority of the “old boys’ club” in SAPOL.

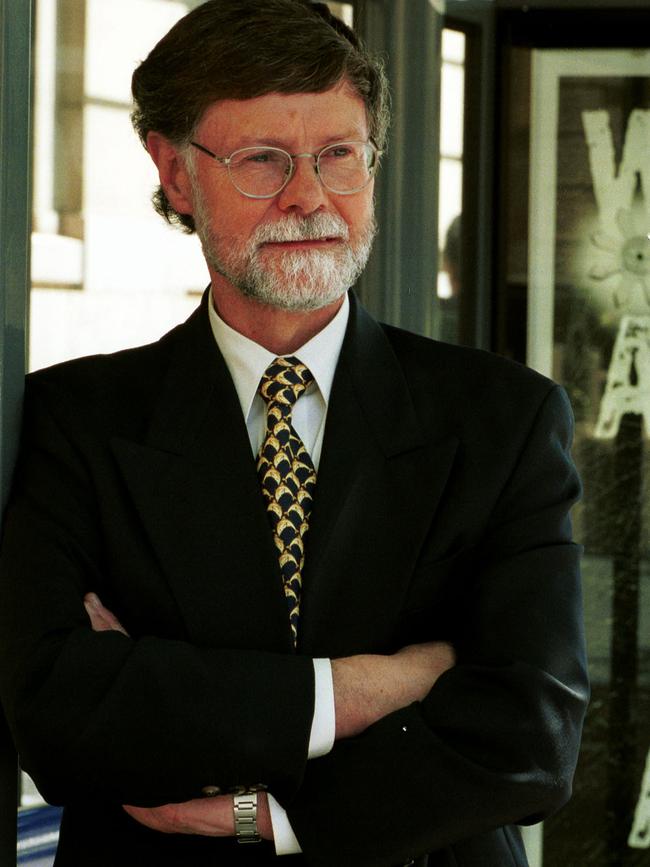

Emerging firebrand and future Attorney-General Peter Duncan used Parliament to air further allegations, revelling in his role as an Elliott Ness-style corruption buster.

Liberal Attorney-General Trevor Griffin was said to be livid with the limp response to four demands to know how the parole system was manipulated to allow the early release of a high-level drug dealer, among other tensions.

He instead ordered a government inquiry over 34 separate corruption allegations against police officers, to be compiled and overseen by their senior colleagues within SAPOL.

Lawyers and drug users and dealers refused to take part and laughed off the seven-month probe as a charade and ‘show trial’.

They claimed the fix was in. In racing parlance, half the field was scratched and most of those remaining were running dead.

On April Fool’s Day 1982, the smart money was proved right. The shorthand verdict was that there was “nothing to see here”.

The 100-page report, reviewed by Supreme Court judge Sir Charles Bright, exonerated police and found none of the 34 allegations warranted action against individual officers.

SA Police were delighted, claiming the report had cleansed the force of odious innuendo while retaining the air of an affronted victim.

The Liberal Government sang from a similar hymn, with Mr Griffin trumpeting the findings as a tick of confidence in police while delivering a short uppercut to The Advertiser.

“Journalists should be on guard against giving credence to, and all-too hastily airing too-vague allegations of a hearsay nature which are lacking in credibility. It only aids and abets mischief,’ he said.

But if police and the government gave the report a five-star rating, the legal fraternity and soon-to-be Premier John Bannon scathingly labelled it a turkey.

Labor and the Democrats lost a motion to force a Royal Commission, which Mr Bannon said was necessary to “restore the high standing of the force as a whole”.

“The report does not clear the name of individual police officers, which is what was desired,” he said.

A prominent defence lawyer flayed the report as “the most unsatisfactory and poorly presented” he had seen, and that “hysterical attacks” by police could not bury the ongoing whispers that some bad apples had escaped unscathed.

Police were bruised and still angry, but it was a win on points for SAPOL and Inspector Moyse, whose staunch defence of the force kept his star shining.

In 1984 he was promoted to head of the state’s Drug Squad, revelling in sanctimonious attacks on drug dealers and users.

The following year, Moyse would betray his sworn duties and the entire force with one greedy and brazen deal that would ruin him.

The scam was simple, lucrative and for a while flawless.

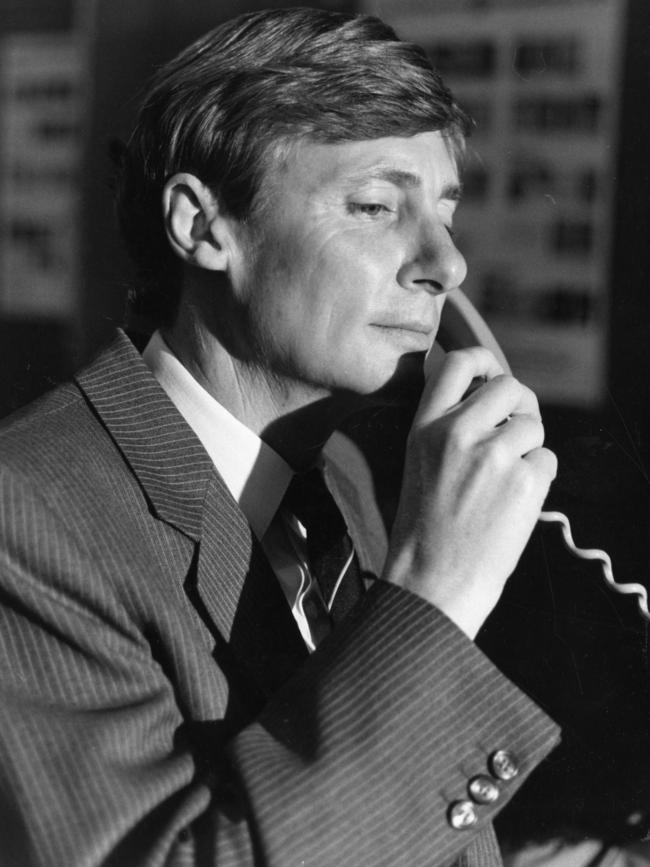

Drugs seized by honest cops would be marked as destroyed by Moyse, who would “recycle” them by giving them to heroin trafficker George Octopodellis for re-sale.

Moyse and Octopodellis’ 50/50 split was a nice earner for both — until the fledgling National Crime Authority came sniffing around SA and accidentally stumbled upon the biggest rat in the police force.

Before the 80s were done, Barry Moyse was in jail and disgraced. Octopodellis fared worse, found dead in his Porsche on a Sydney street from a heroin overdose widely suspected as a deliberate hot shot.

TOMORROW: The NCA came looking for the trophy fish of the SA drug scene, but a young detective called Mick Keelty never expected to hook Moby Dick.