Parole Board of South Australia hearings: Tracking the fortunes of four prisoners seeking release

The Parole Board of South Australia is the gate between prison and freedom for many of the state’s jail inmates. The Advertiser was allowed to attend a board hearing to track the fortunes of four criminals making their case for release.

Law and Order

Don't miss out on the headlines from Law and Order. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“I don’t want to die alone in prison. The game is up for me.”

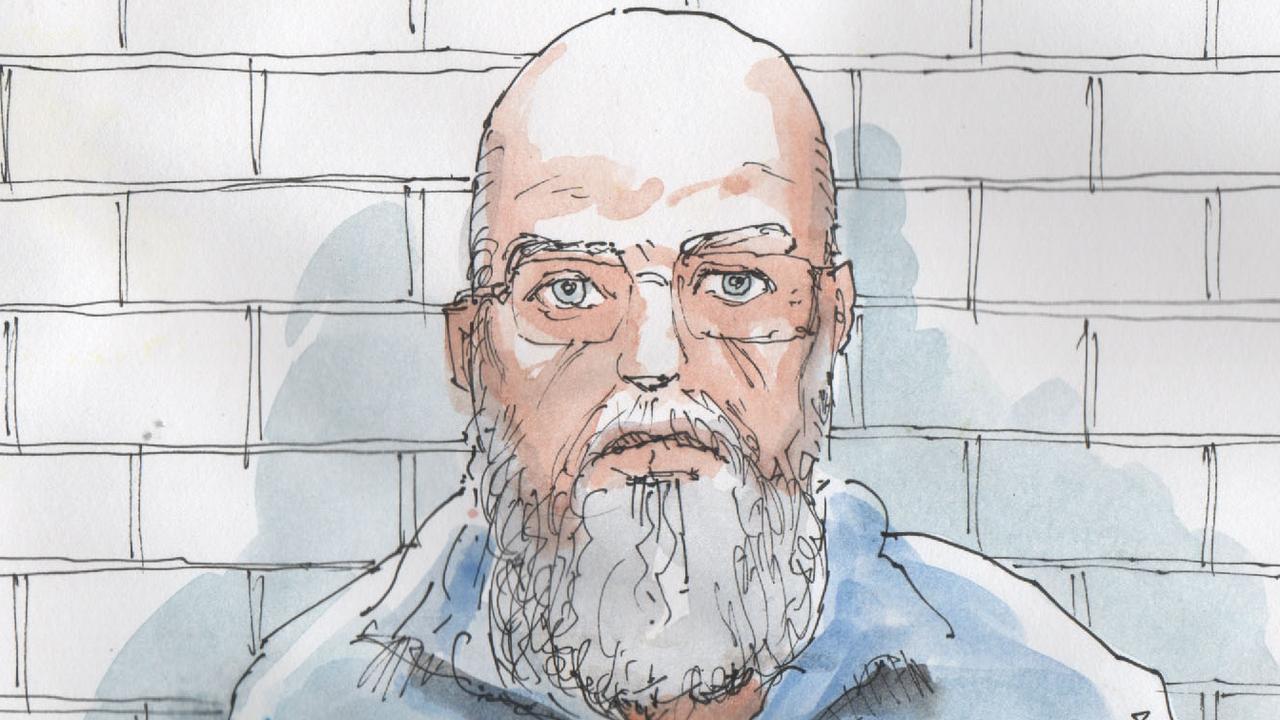

In and out of prison for 40 years, Mark’s hands clasp tightly as he tells the Parole Board his days as a hard man are behind him.

The criminal world – and the one outside jail – bears scant resemblance to the one Mark lived in when he veered on to the wrong path as a teenager.

Since then, he’s shot a man, who survived by pure luck, escaped custody several times, and was last free nearly a decade ago.

Now Mark, who is approaching the wrong end of his 50s, strives to convince the board he is ready, finally, to be a part of “normal” society.

“I’ve got a very good work ethic, all I do is work (inside prison) and I will get work on the outside, that isn’t the worry,” he says, with his focus on the woman in charge here.

Frances Nelson QC has been the presiding member of the board since 1983.

Her diminutive stature and quiet voice belie the power she holds over SA’s 3000 or so inmates.

Ms Nelson is today flanked by prominent defence lawyer Stephen Ey, who joined the 10-person board last year, and Garth Dodd from the Council of Aboriginal Elders SA.

Ms Nelson is afforded the highest respect, almost reverence by would-be parolees.

She and Mark go way back.

“I’ve been in this system longer than you have,” she tells him, in a gentle reminder she’s not hoodwinked by sob stories or false promises.

Mark’s bid for freedom ticks all the boxes and his demeanour is that of a man resigned to having wasted his life.

“I realise now what impulsiveness is. I was catastrophising and avoiding reality and I didn’t even realise I was doing these things,” Mark says. Ms Nelson and her board frequently listen to prisoners extol their new-found sense of empathy, understanding and acceptance of the triggers that led them here.

Institutionalisation, when a person becomes more comfortable in prison than society, looms large in the complex considerations surrounding Mark’s application.

Ms Nelson reminds Mark that when things go wrong and spiral, as they did when he was last released, people can get hurt.

Best intentions pave the road to hell, the old saying goes, and Ms Nelson reminds Mark that another meltdown could be his last chance.

“You have just been lucky, and so have your victims, that you haven’t killed anyone.”

Mark tells the panel that he is under no illusions things will be easy, and understand why the board is worried by his plan to live with the family of an old schoolmate.

Candidly, Mark admits he’s scared of what awaits outside.

“Looking out of the bus on the way here, everything was going so fast. All I thought about was, am I going to be able to adjust to it? It is a concern to me as well,” he says.

The seismic move from his decades of controlled prison life to freedom is a worry for the panel.

Mark’s high-security status precludes him from living in prerelease cottages to acclimatise to life outside.

He admits society is daunting for a man who has languished in a virtual time capsule without the internet or smart phones and online communications.

Mark says he has factored that worry into his plans and vows to work with his parole officer to keep out of trouble.

“That’s why I applied for home detention and electronic monitoring, so it goes slower. I know that I am going to need help,” he says.

“Having home detention means I will be seeing someone on a regular basis. I would refuse to be released back on to the street.”

Concluding his pitch, Mark politely thanks the panel and returns to the cells to wait.

“We are going to have to think about this really carefully,” Ms Nelson tells him.

The panel is encouraged by Mark’s progress, but worry his genuine intentions may not yet suffice.

“Like a lot of ‘tough career criminals’, he is really quite fragile,” Ms Nelson states.

“I don’t think it would take much for him to fall apart.”

They agree that rather than immediate release, Mark’s best hope of staying out of trouble will be to complete his violence prevention course.

Mark’s case is deferred, and he will receive advice on what he has to work on to help sway the board next time.

He will stay in jail for now.

“BRIAN”

Sadly, Brian’s story follows a similar narrative to many of those who end up a cog in the criminal justice system.

A childhood marred by physical and sexual abuse led to him using alcohol and drugs from his early teens.

The dysfunction and drug abuse have wrought a savage toll on Brian, who’s in his mid 30s but looks a decade older.

Brian was released on parole last year and was unable to resist the lure of illicit drugs and the booze.

While he did not commit further crimes, the dirty drug tests led to him being locked up again on a parole warrant.

Today he will find out if his parole is cancelled, meaning he must serve the final four months of his head sentence.

Mr Ey assumes the role of chief interrogator and glances down at a reference from the man Brian was working for.

“We have a reference that says you were a reliable, hardworking employee. How on earth were you managing to do both?” Mr Ey asks.

Deepening the panel’s concern is Brian’s history of drug use, which led him into a deep and dangerous drug-induced psychosis when he was 25.

Brian says the drugs were “a weekend thing”, indicating that the two failed tests were more bad luck than proof he’d fallen off the wagon.

“I think I did pretty well this time, I’m talking about with my anger and my outbursts. I don’t think I raised my voice when I was out,” he explains.

Clearly unimpressed, Ms Nelson retorts: “You didn’t really have a lot of time to demonstrate that you are controlling your temper.”

Brian’s file shows he told his support workers that he had only used drugs twice this time and was unlucky.

But none of the panel are having any of the flimsy story.

“Don’t tell me that the only two times you used, you were tested. This is the time to come clean,” Ms Nelson snips.

Brian lowers his eyes like a chastened child caught stealing lollies.

He admits: “Yes, I used more than twice … and to be straight out honest with you, I was drinking too.”

“Doesn’t leave us with much confidence, does it?” Mr Ey says in a tone that suggests he’s seen this scenario too many times from the other side of the fence, as one of the state’s most experienced defence barristers.

Brian might have been afflicted with the cognitive functioning of a 12-year old, but he can see this is not going well.

“I want to stay off drugs, get a job and go to work, get a girlfriend, and maybe a child one day. I’ve just got to get my head right,” he says in a final effort to win them over.

But those seemingly simple goals are a virtual mirage in the desert for a man with Brian’s background and there is a strong chance this won’t be his last lap of the criminal justice carousel.

The panel decides that releasing Brian now could be “setting him up to fail” and four months in jail will give him time to detoxify and focus on his life goals.

“RODNEY”

Rodney’s explosive violent reaction to life problems has nearly ruined his own and left a trail of bloodied victims, and he is yet to turn 30.

Rodney started drinking at 14, progressed quickly to cannabis and by 18 was smoking meth, ending his brief foray into the workforce.

He’s now on a cocktail of prescription drugs, designed to numb his urges for ice. Ms Nelson notes the dosages are extremely high.

Release on parole means many return to a morass of problems, debts and bad blood that remains outside.

For many, like Rodney, the fines they never paid have sat gathering interest, or other unofficial debts can be demanded from the criminal world they claim to be sick of associating with.

“I won’t be getting a car, I can’t drive and that is 100 per cent my responsibility,” he tells the board.

“There’s no way I will ever be able to afford to pay off a $30,000 debt.”

Rodney says he wants to be a cabinet maker, but he has no licence and won’t have one for many years yet. In a tough job market, his chances of finding an income are far from rosy.

Rodney’s biological father died while he was in jail and his mother is getting older with her own health issues. Rodney claims this has led to a dawning realisation he needs to clean his life up.

“I don’t want to use drugs any more, I am doing this for my family and this time I am doing it for myself as well,” he pleads. “I’m 29 and I’m over it. I can’t go back down that path, I want to change my life.

“I’ve made a promise to walk my mum down the aisle and to her that I will be there.

“If I were to lose my mum while in jail I would never forgive myself. “

Despite encouraging signs of a growing understanding of empathy and abstinence from drugs while in prison, the panel decides that Rodney will benefit from more time under supervision, and to complete a “Making Changes” program to help him cope on his release.

“CHRISTIAN”

Anyone who regards the Parole Board as a soft touch has never seen Ms Nelson in full swing. Just ask Christian.

Ms Nelson has stared down the most violent, disturbed and intimidating parole applicants for nearly 40 years.

She sees through the false bravado that is vital to survival in jail.

Christian’s file shows he was doing well on parole until struck down by gastro, which floored him for weeks and left him without work.

Some are prone to bad luck, but Christian’s story gets thinner as the panel delve into the details.

He was simply too sick to go to a doctor and lost his casual job, and suddenly was back on methamphetamine and failing drug tests, he claims.

It’s an oppressively hot day outside and Mr Ey channels the role of magistrate or judge rather than his day-to-day gig as the man defending the likes of Christian in court.

“That seems a very poor excuse to resort to use of methamphetamines?,” Mr Ey says with impatience.

Perhaps realising the “poor me” card won’t work, Christian launches into an impassioned plea that this will be the last time they see him if the panel will just give him one more chance.

“I’ve had it up to here. I’m 40 tomorrow,” Christian says in a self-berating hiss.

“My partner is sick of it, it’s the best relationship I’ve ever had and I’m on the verge of throwing that away. My own children have pretty much grown up without me.”

“Doing it for the children” is a common theme, yet this pledge fails to impress Mr Ey. “You’re a grown man. When you’re going out and scoring methamphetamines are you thinking of those children then?” he asks.

Ms Nelson has heard the spiel too many times before.

“You are no stranger to the system. This is your fourth parole and you have breached all of your paroles,” she says.

“At some level you have to say I’m responsible for my own life and there are things I can do to improve my life.

“I do not think you’ve got to that stage.”

Christian smiles, thanks the board and is led away back to jail.

None of the quartet will be returning to their homes yet, and can only quietly toe the line inside until they confront their greatest challenge – making a go of life outside.