Veteran detective slams SA Police’s toxic work culture after colleagues death at Port Adelaide station

A veteran officer has blasted SAPOL’s response to a shocking incident in the Port Adelaide Police Station. Warning: Distressing content.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A veteran South Australian detective has blamed SA Police’s toxic work culture and claims a “horrendous” mental health support system for almost driving her to suicide.

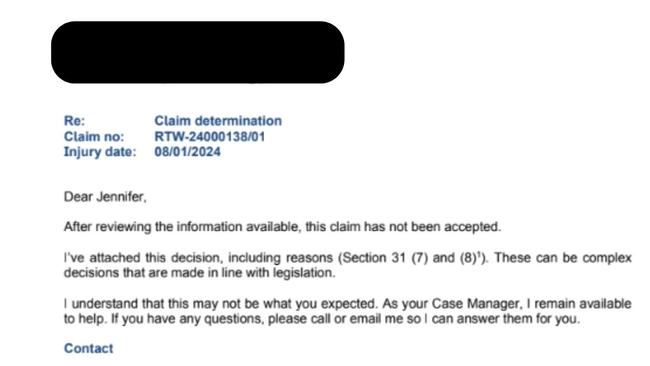

Detective Brevet Sergeant Jennifer Favorito has revealed how SAPOL rejected claims her mental health was hit by the death of a close colleague at Port Adelaide Police Station in January.

The detective, who has worked for the state’s force for 20 years, is now obliged to pay back all psychiatric and medical costs, including all wages, to SAPOL.

“Her desk was to the right of me,” explained Ms Favorito, who had known the colleague for almost two decades.

“But it was like, someone moves into (that desk) straight away. It was like nothing had happened.”

SAPOL rejected Favorito’s claim despite three different health professionals stating she showed signs of PTSD and depression sparked from the incident.

“I just feel so let down. I knew they weren’t going to help. I was hoping they would prove me wrong but they didn’t,” she said.

“Being a detective is my identity. It’s all I have known since I was 22.”

The seasoned detective admitted she has “seen the worst of the worst” over her career, working extensively with domestic violence and child abuse victims.

But the 40-year-old struggled when “it was business as usual” just days after the close colleague suicided in the toilets of Port Adelaide Police Station.

“When I walked into work, everyone was (acting) as if nothing had happened,” she explained. “No one was talking about it. I was talking to my close friend and I was asking why no one is talking about it and pretending like nothing had happened.

“And I was like, ‘I am not going into those toilets. They were closed on that day (of the death) but then they were back open by the time I returned to work. I was told the one tile, where the bullet hole had been, had been taken off but everyone was just using the toilet as normal.”

Ms Favorito claimed there’s an ingrained culture within the force that to seek help for mental health is a blocker to any career progression and was a “black mark” on your record.

“There is this toxic work culture,” she said. “You can’t trust anyone. You can’t talk to anyone. You have to show no weakness.”

And it was this ingrained mentality which made her initially not seek help. She added, “I kept thinking, ‘What was wrong with me?’.”

Instead, over the next few months, Ms Favorito started feeling overwhelmed by her workload, was struggling to get out of bed and regularly arriving late at work. All the telltale signs she was “not right”.

But the detective claimed no one at SAPOL came to check in and offer any support.

In early April, she felt at her lowest and called in sick.

She booked in with her GP who signed her off work for a week. “I was ready to quit,” Ms Favorito explained.

Instead SAPOL urged her to talk to a social worker from the SAPOL-linked Corporate Health Group, and she was asked to fill in a number of forms.

One of them was to waive confidentiality from psychiatry sessions. The other was a Work Safe Injury claim form, which she admits was “difficult” to fill in as it was more tailored to a physical ailment rather than mental health.

And within this form, it stated that if SAPOL rejected her claim she would have to pay back all medical costs and wages paid during that time.

Over the next six months, Ms Favorito saw the force’s GP, a psychologist and was in regular contact with the SAPOL. But she was struggling on improving her mental health as she was concerned about the mounting cost.

It took six months for SAPOL to organise a psychiatrist, the only person who could prove her mental health was impacted. By that time she had racked up thousands of dollars in medical costs and wages.

“The psychiatrist said there was evidence of PTSD and depression and he said it was work related,” she said.

But on October 10, SA Police rejected the claim on the basis she had not been in the station on the day the incident happened and her written statement was not suitable.

All SA Police-subsidised psychiatry consultations were immediately pulled, including all funding for the force’s GP. She is now only being paid a minimal base salary to support her family, with two young kids.

“Everything was cut off,” she said. “I now can’t afford to see a psych.”

By her own admission, the past year has broken her and it almost drove her to take her own life.

“The reason I am here is because of my kids. You just don’t know how you are going to get out of that space. It’s too painful. You can’t see an outcome,” she said. “I couldn’t leave the kids. I just couldn’t think of doing that to them … but, if thekids weren’t there, I would have done that 100 per cent.”

Sergeant Favorito has now sought legal advice, with a lawyer subsidised by PASA, and is fighting the claim rejection.

An SA Police spokesperson said: “SA Police recognises health and wellbeing as critical element of having a high functioningand resilient workforce able to provide policing services to the community.

“Employees have access to psychosocial support 24 hours a day, seven days a week. In addition, SAPOL provides employees with access to numerous health and wellbeing programs and services.”