NCA bombing: Prosecution case against bomb suspect Domenic Perre revealed for the first time in 26 years – Part 1

The $20m drug crop, the undercover police calls and the death threats – prosecutors have pulled back the curtain on 26 years of investigations into the 1994 NCA bombing.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

At 9.15am on March 2, 1994, a homemade bomb exploded in the Waymouth St offices of the National Crime Authority, killing one man and severely injuring a second.

But while the device that killed Detective Sergeant Geoffrey Bowen and burned Peter Wallis had been made just weeks earlier, prosecutors say its fuse had been burning for some time.

It wove its way, they say, from a $20 million drug crop through personal slights, insults, FBI-style surveillance training and bomb-making books to a carpark on Pitt St.

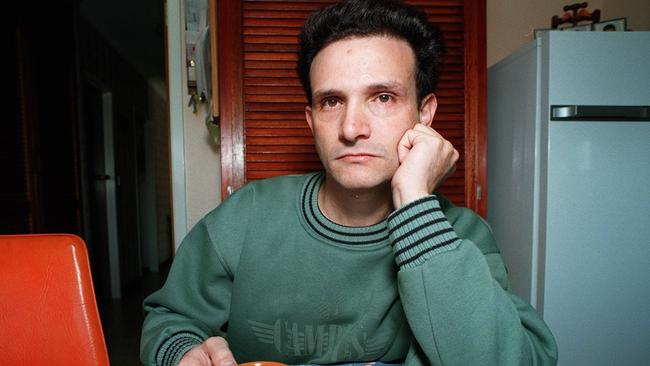

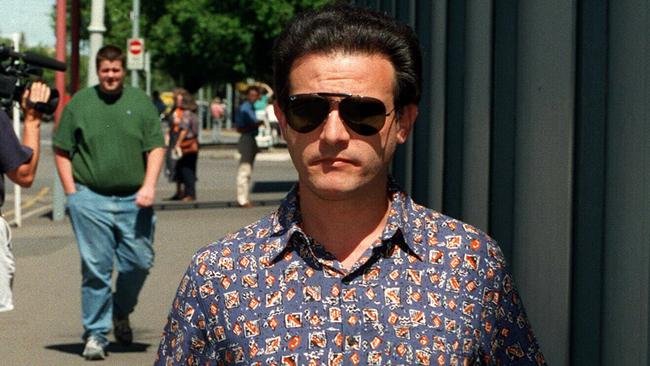

There, prosecutors allege, Domenic Perre stood and watched the offices burn – the end result of his well-developed, festering hatred for police and for Bowen in particular.

This week, 9729 days after Adelaide’s first major incident of domestic terrorism, prosecutors finally pulled back the curtain on their case against their longtime prime suspect.

Instead of an opening address, prosecutor Sandi McDonald SC has outlined the evidence against Perre, now 63, in a document filed with the Supreme Court.

Over 60 pages, she describes three decades worth of information from dozens of witnesses, forensic experts, prison informants – and a criminologist specialising in the Mafia.

But for all the complexity of the long-unsolved case, Ms McDonald alleges Perre’s motivation was simple, timeless and rooted in the most base of human emotions.

“ (Perre had) a hatred toward law enforcement and, ultimately, toward the NCA and Bowen in particular,” she writes.

“That hatred developed and festered, and ultimately led to the death of Bowen.”

HIDDEN VALLEY, LOST MILLIONS

Bowen, a serving member of WA Police, arrived in SA in July 1992 to serve a secondment with the NCA which was, at that time, targeting Italian organised crime.

Though he would, Ms McDonald asserts, come to be the centre of Perre’s ire, he was not involved in the incident that sparked the alleged murderer’s animosity.

That happened in August 1993, when NT police found $20 million worth of cannabis at Hidden Valley Station, more than 650km south of Darwin.

The station was, Ms McDonald alleges, being operated by Perre and members of his family – his brother, Francesco, was the first to be arrested.

That allowed Senior Sergeant Simon Young to take over the station’s landline, pretend to be Francesco and answer all incoming calls.

Several of those calls were allegedly made by Domenic Perre, who started the first by saying: “You’d be a f---ing idiot, it’s me, Dom, your brother.”

Young and his team decided to employ a ruse that the crop was being “ripped off” by a rival gang, allegedly causing Perre to offer up the drugs so long as his men were not hurt.

The deception fell apart when the real Francesco was allowed to make a telephone call from custody – causing Domenic Perre, prosecutors allege, to call Hidden Valley in a fury.

“Get f---ed you son of a bitch, if I ever get my hands on you I’ll waste you,” Perre allegedly told Young.

“It is the prosecution case that this was the beginning of a hatred towards law enforcement … that developed and festered over coming months and ultimately led to the death of Bowen,” Ms McDonald writes in the document.

“Perre had been one of the main players behind the organisation, setting up and financing of the Hidden Valley cannabis crop.

“Not only were family, friends and associates arrested and held in custody, but Perre and others lost a cannabis crop worth in excess of $20 million.”

A DEVELOPING ANIMUS

Shortly after the “fake Francesco” calls, Bowen was tasked as the contact point between the NCA and NT Police.

“The operation was given the name of ‘Vulpino’ and Perre was a principal target,” Ms McDonald writes.

“At the time of his death, almost all of the work being undertaken by Bowen was on Vulpino, with Perre being a principal target.

“It was as a consequence of the manner in which Perre was targeted and his family was treated … that the animus by Perre toward Bowen developed.”

In September 1993, Bowen led a covert raid of Perre’s unattended house at Salisbury, seizing electronic equipment used to intercept communications.

He left behind his other discoveries, including pornographic video tapes and imitation security officer badges.

“By the end of the search, the house was in a state of disarray – the investigators left the house in that condition,” Ms McDonald writes.

Perre, she says, attended Para Hills Police Station to complain about the “break-in” and made an allegedly false report about firearms having been stolen.

He also, she says, called a top-ranking NCA officer and said: “Your investigators need to have some lessons or instructions on how to leave places after they have searched it.”

Perre allegedly mentioned Bowen by name, saying he had made a video recording of the state of his house.

A week later, Bowen arrested Perre over the interception devices – it is alleged Perre “appeared to be shocked” by the situation.

Ms McDonald says another NCA officer will give evidence that Bowen “constantly goaded and belittled” Perre, displaying a “demeaning and harassing” attitude toward him.

“Bowen ridiculed Perre about the security badges that he had at his house saying things like ‘where’s your security officer’s badge?’ and ‘where’s your sheriff’s badge?’,” she writes.

“Bowen’s behaviour was such that, at one point, (the other officer) reminded him that there were CCTV cameras present.

“Throughout all of this, Perre showed no reaction to Bowen’s behaviour … he stood staring fixedly at the wall, refusing to respond in any way.”

The final straw, Ms McDonald alleges, came later that month when Perre’s mother, Maria, died – and Francesco was denied bail to attend her funeral.

“It is the prosecution case that this slight to the Perre family would have only further negatively impacted on Perre and his attitude toward law enforcement,” she writes.

THE HONOURED SOCIETY

Ms McDonald writes that the importance of family, in Perre’s life, cannot be overstated.

As such, the trial will hear from Dr Anna Sergei, an associate professor in criminology from the University of Essex in England.

“Her area of academic specialisation is the study and research of the Italian Mafia, specifically the Calabrian ‘Ndrangheta or ‘Honoured Society’.

“More particularly, she has been one of few academics to engage in an Australian criminological study of ‘Ndrangheta in Australia.”

Ms McDonald says Perre’s family originated from the town of Plati, in the Calabrian region of Italy – and alleges they were one of its “main ‘Ndrangheta families”.

“Regardless of whether Perre identifies as a member of ‘Ndrangheta, he and his family have been raised and have lived in that culture,” she writes.

That, she asserts, means Perre’s outlook has been impacted by six key components of the Mafia lifestyle, namely the:

IMPORTANCE and sanctity of family.

ROLE of women in the family, and how women are viewed by that culture.

SANCTITY of the family home.

GENERAL distrust of authority.

IMPORTANCE of rituals and funerals, and expectations as to attendance.

CULTURE of silence, known as “omerta” in which it is “frowned upon to speak to or assist law enforcement in any way”.

AN IMMEDIATE IMPACT

Following Hidden Valley and his own arrest, Ms McDonald alleges, Perre spoke with three people – and his dealings with them demonstrated the true impact of Bowen’s behaviour.

The first was Ray Jarvis, owner of a US-based company that provided security training for law enforcement, military and intelligence agencies.

Perre, Ms McDonald asserts, had been a customer of Jarvis since 1991 and an attendee of his courses in both basic and advanced “eavesdropping countermeasures”.

She says Perre wrote to Jarvis and his wife, Cindy, in January 1994 complaining about the NCA – and including a copy of court documents filed, against him, by Bowen.

“The NCA, the equivalent of your FBI, wished to ask me some questions … I turned down their request and refused to participate in any form,” he wrote.

“In an act of vindictiveness I was bluntly told that I would be charged with the possession of interception devices.”

Perre, she says, told Jarvis he believed such devices were “in daily use by all members of the public”, particularly scanners that picked up police radio communications.

“It would seem that they have double standards for harassment purposes and to be educated in this field is a crime in this country,” he wrote.

“Their advantage is that we do not enjoy constitutional rights and our nation is heading more and more towards a totalitarian system.

“Some of our protectors could teach the Nazis a lot.”

The second person, she says, is a key player in the trial – a man named Allan Chamberlain.

In 1994, Chamberlain was, like Perre, a customer of the Central Firearms gun shop at Prospect.

Chamberlain often undertook gunsmithing work for the business’ owner, Sam Tettis, and came to know Perre as a result.

Ms McDonald says that, during one post-Hidden Valley conversation in the business’ car park, Perre was “uncharacteristically dishevelled and unshaven”.

“Perre’s demeanour was also unusual in that, whilst he was ordinarily measured and thoughtful, on this occasion he was more animated,” she writes.

“He told Chamberlain that he was acting as liaison for the family, amongst other things, to arrange lawyers and post bail.

“He said that, between taking time off from his business and his own court case, he was finding it hard.

“He said the NCA were ‘breaking his balls’ and it was costing him a lot of time and money to fight the court case (which was) playing on his mind.”

The interception device charges, she says, were supposed to go to trial on March 3, 1994 but was delayed – one of several adjournments that left Perre “upset”.

The third person with whom Perre spoke, Ms McDonald asserts, was a drug dealer who was friends with his cousin, Sam Catanzariti.

She says the dealer was present for a conversation, after Hidden Valley was raided, between Mr Catanzariti – who will not be called at the trial – and Perre.

“There was a heated discussion that was partly in English and partly in Italian,” she writes.

“The two men appeared to be quite angry and animated in their conversation … Catanzariti said something like ‘how we gonna fix this c---?’.

“In response, Perre said ‘with that there’ and pointed to a box on the dining room table.

“That box was light brown, rectangular and closed … it was approximately 12-14 inches long and 7-8 inches wide.”

That box, on the prosecution case, contained the bomb that would kill Bowen and leave Wallis with injuries that plagued him for the rest of his life.

WEDNESDAY ON ADVERTISER.COM.AU – PART 2: A RECIPE FOR SURVIVAL, C4’S UGLY SISTER AND SMUGGLING MADE EASIER