How SA’s prison system headed towards chaos in the 1970s

CARROTS rather than sticks was the mantra for rehabilitation inside SA prisons in the early 1970s — but many not only ate the carrot, they stole the stick and broke out of the cage. Here is how social upheaval sparked tensions inside our jails between guards and inmates with a rise in escapes and violence.

- Prison guard protest: SA Correctional services CEO reviewing footage

- SA prison guard rally against privatisation

CARROTS rather than sticks was the mantra for rehabilitation inside South Australian prisons in the early 1970s, under Don Dunstan’s pioneering Labor government.

But many not only ate the carrot, they stole the stick and broke out of the cage.

And a decade of good intentions ended in looming chaos and violence, especially in Yatala Labour Prison and the now-defunct Adelaide Gaol.

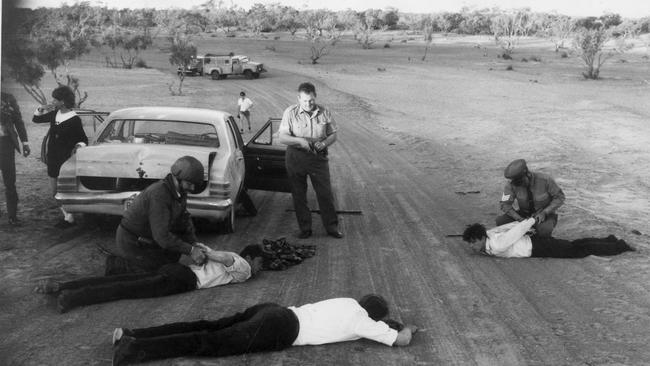

Escapes increased, as did violence among inmates controlled by a “mafia” of convicts, while prison guards and administrators fell into dispute over a system seemingly out of control. In September 1970, the national spotlight fell upon SA prisons when three escapees and kidnappers were arrested at gunpoint on the Birdsville Track.

Low-security “trusted” inmates at Cadell in the Riverland, Terry Haley, Raymond Clifford Gunning and Murray Andrew Brooks were all serving housebreaking sentences and due for release early the following year.

But they failed to return from an unsupervised afternoon walk and instead trekked about 12km through scrubland to the Schiller farm at Murbko in the upper Murraylands.

The escapees seized a 12-gauge shotgun, tied members of the family up and then ordered their 21-year old daughter Monica to come with them in the Schiller family’s car.

The brazen kidnapping sparked a huge manhunt, with grave fears the engaged Monica Schiller could be harmed or killed.

Together they drove north along rugged roads before being spotted by police aircraft near Clifton Hills, about 150km south of Birdsville.

They hid alongside buildings before being confronted by armed police — accompanied by The Advertiser reporter Brett Bayly and photographer Ray Titus, who captured incredible action shots that have become iconic images in Australian crime reporting.

Miss Schiller soon after married her fiance — and the trio received hefty 15-year jail terms for their escapade.

Despite his crime, Haley was soon considered as a “trustie” by prison authorities and in January 1972, wandered away from Yatala with three other inmates from an authorised tennis match on a court outside the prison.

Monica was bemused, along with most South Australians.

“I didn’t think they would let Haley out to play a tennis match,” she said.

It was an embarrassment for authorities, but far from the last they would endure in a tumultuous decade of trial and error.

Prisoners leaving the grounds to play sport was banned at Yatala, where guards asked for radio communications so they could alert each other to any problems.

The Comptroller of Prisons, Mr L Gard, bemoaned a system run by “so-called psychologists, psychiatrists, idealists and theorists”.

Mr Gard said the well-intentioned reforms were instead “gambling against the public welfare”.

“Sooner or later, the public will get up in arms about this warped sentimentality and demand a more realistic approach,” Mr Gard said.

His prediction was right. It would just take a long time and a lot of suffering before things changed.

The farcical escape of convicted killers and part-time puppeteers Noel Russell McDonald and John Michael Farnsworth from the 1973 Royal Adelaide Show sparked a five-day manhunt and a longer witch-hunt.

A subsequent review of the Royal Show puppet show drew the wrath of the Crown Solicitor

“Much too ambitious,” the Crown Solicitor found.

“It placed in the way of these prisoners temptation to escape which was too much for them,” the Chief Secretary said.

“Prolonged theatrical performances by prisoners in public” were banned from then on.

It also spelt the end of the Yatala Labour Prison Puppet Troupe, which fell away along with a Poetry Club that ran on Sunday afternoons and had won a Federal Government grant.

Musicals produced by inmates and performed to the public fell by the wayside, but the brazen escapes continued unabated.

In mid-1974, a television station chief received a menacing piece of viewer feedback, in the form of a rifle and television set — hand delivered to the newsroom.

On June 11, 1974 a young inmate was recovering from a hernia operation in Modbury Hospital when he escaped, only to be caught soon after in company of people harbouring him.

But on June 15, he bolted from the hospital again, narrowly avoiding capture several weeks later when police spotted him in a car with another man and a girl.

The .22 calibre rifle and television set were dropped off at Channel 10’s Gilberton studios, later the home of Channel 7, after the bulletin on the night of August 6

Two messages, titled “Dear Newsman” and “The chief of the CIB”, were taped to the weapon along with the TV set, with a note stating it was “a gift to the news reporters” that had been stolen from the 277 Motel at Glenunga.

In neat capital letters, one of the messages stated “Guns don’t win battles. To the chief of the CIB. This is the Escapee’s Gun.”

Rapists, killers and armed robbers were often at large, and while some were respectful or even charming to those they came across, some were desperate to create mayhem before they were captured.

A teenager who fled Yatala in 1976 with a pitchfork then went to the northeast suburbs home of a married woman and brutally raped her while threatening to garotte her with a piece of wire.

If such an escape occurred today it would be the source of outrage, yet in October 1976 it drew “concern” from authorities and a warning from a Police Chief Superintendent.

“It is important the public should know that there are people about who resort to all sorts of conduct when they are free,” he said.

Among that group was 23-year old escapee Marc Anthony Phyland, who in July 1976, pinched a Yatala guard’s personal car and drove it through heavy gates to a brief period of freedom.

Phyland armed himself with a large metal file stolen from the Yatala workshop and robbed a mother at her Ingle Farm home.

But when he then went to the Domenican Roman Catholic Convent at Salisbury, his plans for another soft robbery went awry when Sister Margaret Wallace answered the door about 10.30pm.

The nun grappled with the 23-year old escapee, and “started screaming”, while Phyland repeatedly told her to shut up.

“I eventually got the file away from him and I think he became frightened. I think he knew others would come once they heard the screaming,” the plucky nun said.

The prison guards were also unhappy and had threatened strike action over issues including when they received paychecks, as a growing sense of apathy developed.

Many prison guards, especially old-school screws hardened by a military background, felt the swing away from iron-fisted rule over inmates had gone too far.

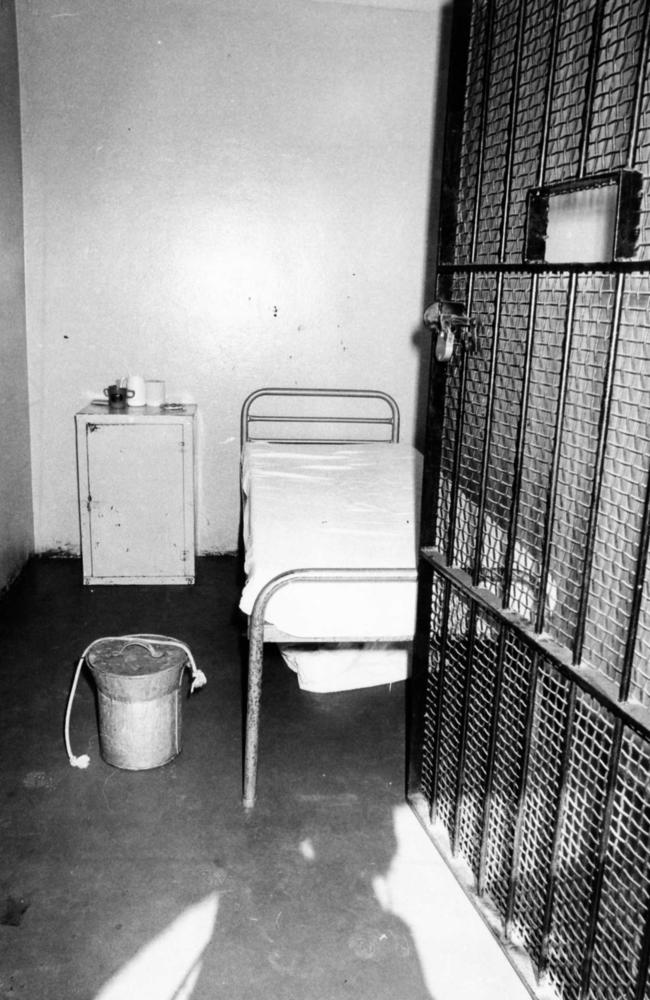

They were increasingly held to account for issues out of their control but but prisoners could now sport long, flowing hair, had access to books and newspapers and could put posters on the walls of their cells, in which they spent 13 ½ hours a day.

But all struggled with life inside the damp, depressing and unhygienic setting of their uneasy relationship.

In the mid-70s. an experienced guard told The Advertiser there was a new conditional degree of respect from guards towards convicts.

“We don’t use autocratic leadership. We treat them with courtesy and we expect courtesy back. If somebody speaks to me like a bastard then I will be a bastard,” he warned.

While the Labor government advocated reform, it could never achieve it while unable to afford to fix the third-world conditions of the now-defunct Adelaide Gaol and Yatala Labour Prison, which at that time remained a relic of the 1850s.

Neither had power points inside cells, because at Yatala it would be cheaper to build a new facility then drill through the thick walls, while the Adelaide Gaol never had toilets and forced inmates to use buckets in their cramped cells.

A Royal Commission set up in the final years of the Dunstan government later found there could be no real prospect of widespread reform inside such decrepit buildings.

The Commissioner also found improper use of equipment and abuse of rules was rife from both staff and inmates, some of whom had formed a core group which wielded power among the prison population.

Aboriginal over-representation inside jail and a spate of suicides and suspicious deaths in the late 1970s and early 80s led to allegations that staff had turned a blind eye to the “mafia” of inmates running the show.

By the end of the 70s and the Labor government’s rule, Adelaide had lost any veneer of innocence through a series of murders and unsolved crimes which still haunt the state.

The Truro serial murders, the early victims of what would be dubbed the Family Murders and the disappearances of Kirste Gordon and Joanne Ratcliff from Adelaide Oval had all added to the sense of unease which started with the 1966 disappearance of the Beaumont Children.

Dr David Tonkin took the reins as Liberal Premier in September 1979, inheriting a prison system on the verge of chaos.

By the end of the Liberals’ rein of less than three years, prisoners were threatening to riot, bash their captors and burn Yatala and Adelaide Gaol to the ground.

This time, the crooks were true to their word, and the 1980s would be a wild and fiery ride inside South Australian prisons.