How ‘Paddy the Pig’ conned Melbourne racegoers

Armed with a trained monkey, a barrel of marbles and a swag of tricks, gang leader “Paddy the Pig” swindled the crowds at Melbourne racecourses with his crafty cons and sleight of hand. LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

True Crime

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime. Followed categories will be added to My News.

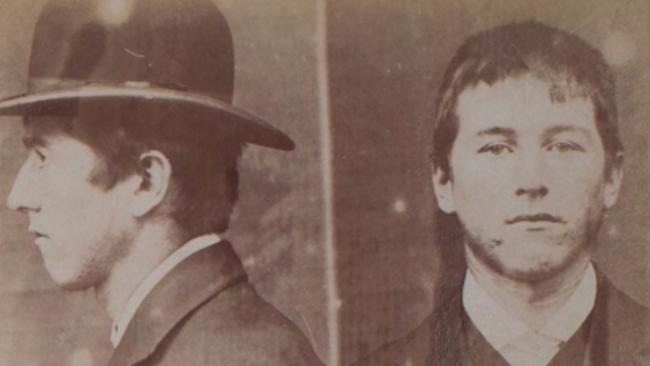

Frank Curran, alias “Paddy the Pig”, was the leader of a gang of conmen who targeted crowds at Melbourne’s racecourses during the early 1900s. He was violent, crafty, and seemed untouchable until police finally shut him down.

Paddy the Pig is the subject of the fourth episode of our five-part miniseries on old Melbourne’s craftiest conmen in the free In Black and White podcast on Australia’s forgotten characters.

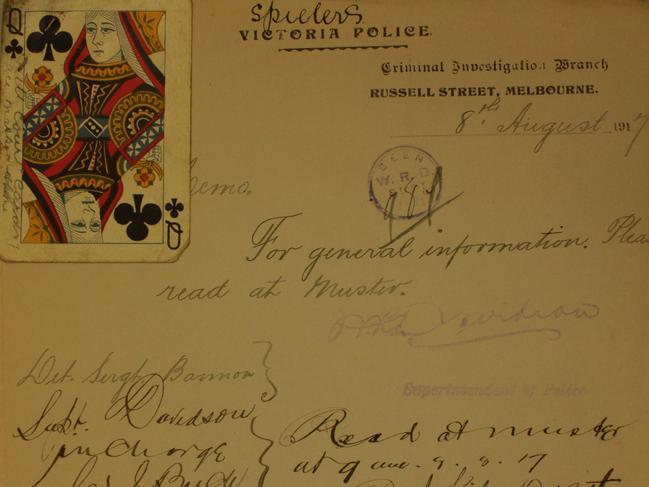

In Melbourne, in the early 1900s, conmen were referred to as “spielers”.

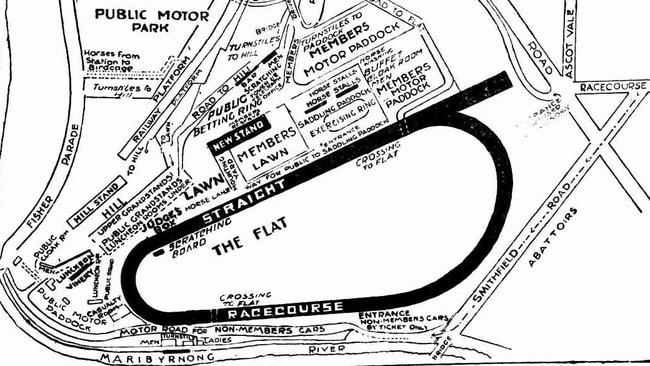

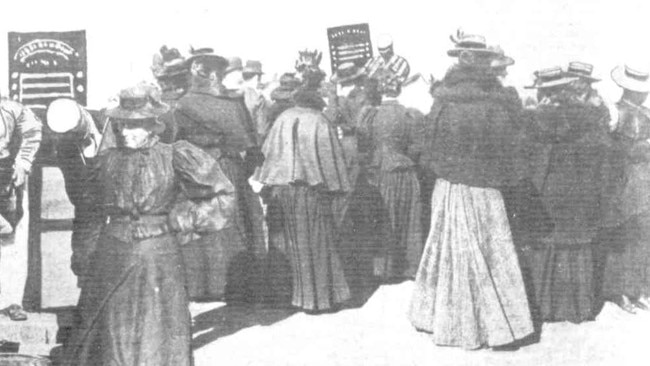

They were plentiful at horseracing events, particularly in the cheap admission section known as the “racecourse flat”.

The racecourse flat was an area for spectators contained within the centre of the racecourse.

The track was a boundary which separated the poorer race goers from those who could afford to populate the areas around the outside of the track, where there were better amenities with grandstands, bars etc.

The flat was largely without seating, shade, or shelter, and was packed with colourful characters and criminals of all types.

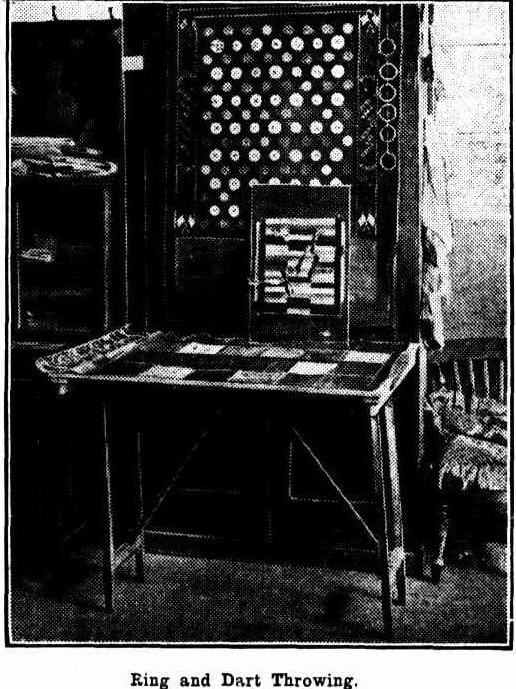

On busy race days, sections of the flat would become a virtual sideshow alley of illegal gambling games.

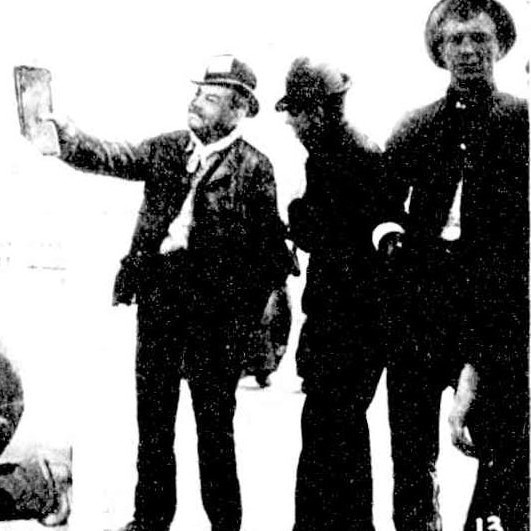

The spielers that ran the games were consummate entertainers, competing for crowd attention.

The games included Roulette, Pea and Shell, Three Card Trick, and others that sounded more exotic such as Indian Darts, Yankee Sweat, and Monkey and the Marble.

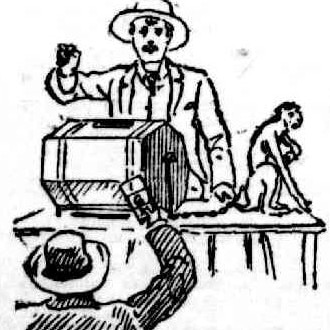

The Monkey and the Marble game was particularly entertaining. The spieler would arrive with his trained monkey and set up a barrel.

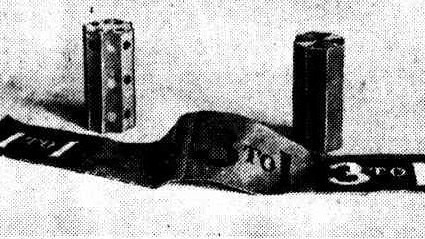

The barrel was similar to the ones used today for lotteries and raffles. Inside the barrel were marbles with numbers on them. A tablecloth would be laid out on the ground.

The tablecloth was printed with numbered squares so the crowd could place money on the number they chose to bet on. After bets had been placed, the spieler would spin the barrel, open the lid, and the monkey would reach in, pull out a marble and hand it to him.

The spieler would then hold the marble up for inspection and announce the winning number. The game was rigged because the spieler had other marbles hidden up his sleeve and would use sleight of hand to produce a number nobody had bet on. The deception was so clever that it once caused a policeman to be laughed out of court for claiming that the game was rigged because the monkey could count.

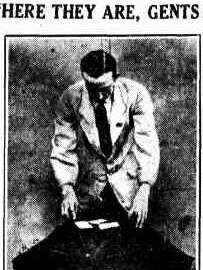

The most common game on the flat was the Three-Card Trick, also known as Three-Card Monte. The spieler folded out an umbrella as a makeshift table.

He’d show the crowd three cards, usually two blacks and a red. It was the task of the crowd to pick which of the three was the red one.

The spieler would then place the cards face down and slowly swap them around.

The game looked easy, especially when other members of the gang, posing as general punters, were placing bets and winning.

As soon as the rest of the crowd began to bet though, the spieler would go into card-trick mode and the punters would lose.

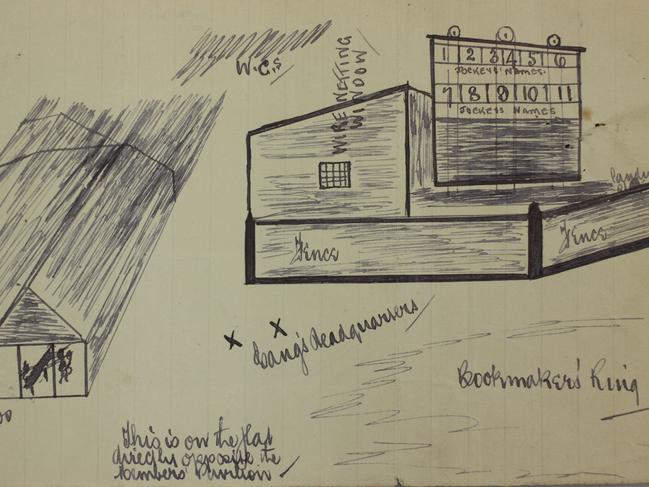

The spielers operated in gangs of up to twenty and they all had their role to play.

There was the showman to run the game. There were clerks to accept bets and pay out winnings. The ‘buttoners’ were there to pose as punters. They’d place bets to urge the crowd into participating and generally they were the only ones to win.

There were also the “cockatoos”, who let out a squawk if the police were coming. And finally, the ‘muscle’: they sorted out any troublemakers.

The boss of Melbourne’s racecourse spielers in this era was Frank Curran alias “Paddy the Pig”.

He kept an eye on things from his vantage on top of a kerosene box in the crowd.

The police seldom intervened, and when they did, they felt his wrath. On more than one occasion he attacked them with his fists.

Registered on Curran’s prison record were terms for robbery with violence and living off prostitution.

His racecourse gangs were made up of Melbourne’s most seasoned and expert crooks, including a young Squizzy Taylor.

In a 1917 police report, Detective Napthine said of Curran: “I have known the accused for about 14 years. He is one of those men who organises little gangs at the racecourses to cheat the public. He sometimes stands on a box acting as watcher and gives the alarm at the approach of a detective or policeman.”

It was in 1917 that police decided to bring an end to Curran’s reign.

They arrested him for vagrancy, and he was sentenced to 12 months in prison.

The judge cleverly suspended the prison sentence on the condition that Curran stay away from racetracks. Problem solved.

Curran had been banned from his preferred place of work, and with persistent police attention most of the spieling games of old slowly died away.

A few, like the Three Card Trick, have stood the test of time, but you’re unlikely to find them played in the middle of Flemington Racecourse on Melbourne Cup Day.

Michael Shelford is a Melbourne writer, researcher, and creator and guide for Melbourne Historical Crime Tours.

Listen to the interview with Michael Shelford now in today’s new free episode of the In Black and White podcast on Australia’s forgotten characters on Apple/iTunes, Spotify, web or your favourite platform.

And check out earlier stories in our series on old Melbourne conmen: shonky undertaker Rev Charles Jones, who registered his own church to save on funeral costs, Smith Brown, the 1840s ex-convict who swindled Melburnians with one simple trick, and “Flash Jack” Donovan, who made a fortune from Ned Kelly’s hanging.

And see In Black & White in the Herald Sun newspaper Monday to Friday for more stories and photos from Victoria’s past.

inblackandwhite@heraldsun.com.au

Originally published as How ‘Paddy the Pig’ conned Melbourne racegoers