Gangs demolished, bikies quit as new laws, police tactics prevail

It took a bloody gang shootout at a city nightclub for the state government and police to declare war on the bikies. Just over a decade later, Adelaide’s streets are a safer place.

True Crime

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Former Finks bikie Dylan Jessen returns to amateur footy

- SA corrections officer texted information to bikies

- Senior bikie jailed indefinitely for refusing to answer questions

The number of bikies in South Australia has plummeted following the disintegration of the once feared Mongols bikie gang.

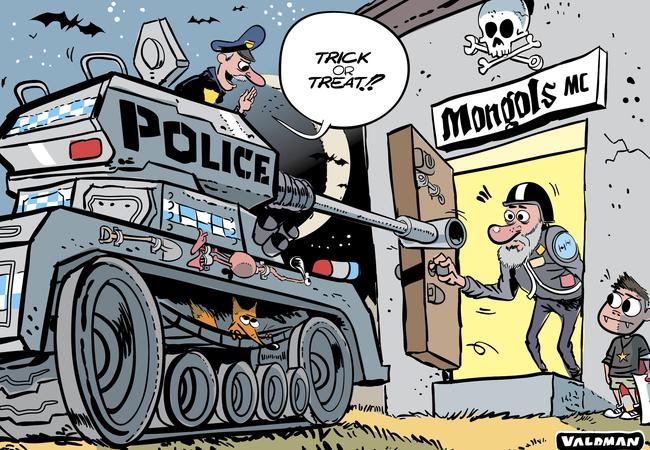

Unrelenting police pressure, combined with watertight anti-bikie laws have eliminated all chapters of the Mongols and resulted in other gangs losing significant numbers of members.

Senior police have revealed gang membership dropped to 196 in December, but have increased slightly to 205 this month – a decrease of more than 30 per cent in three years.

Assistant Commissioner (Crime) Scott Duval said eliminating the Mongols from SA was “a good achievement’’.

“It is significant and another good example of how the legislation is working,’’ he said.

“Anytime these gangs are in conflict there is a risk to public safety.

“If you eliminate a gang that has a predisposition for violence, then the streets really have to be safer.’’

The implosion of the Mongols follows the eradication of the Nomads and Bandidos chapters in Adelaide in 2015.

While there are still seven other gangs still functioning in SA – with the Hells Angels the largest – they have all been weakened with many losing key members who have either left because of police pressure or relocated overseas but continue their involvement.

Key components of the anti-bikie legislation that were introduced in 2015 – including dismantling of clubrooms, anti-association orders that prevent gatherings and a ban on wearing colours – have prompted gang members to adapt their activities to survive.

But while public safety has been considerably improved, their involvement in organised crime – such as drug trafficking and money laundering – continues.

“We have removed the public persona of OMCGs and reduced a lot of fear in the community, but we have not eliminated the criminality either by the gang collectively or individually,’’ Mr Duval said.

“Bikies have business model and as it adapts to pressure from law enforcement we have to look at our own methodologies and that may mean looking at different aspects of legislation.’’

Mr Duval said he didn’t believe there was one single aspect, but rather the collective package of measures in the legislation that has delivered this result.

“The fact they are declared organisations, the fact they cannot gather in public, they can’t wear colours, the dismantling of their clubrooms, the total package is the strength of it,’’ he said.

“There is not one area that is now exposed. When you combine all of that and still keep up strong enforcement against them of the standard offences that are still there, the drugs, the violence, it creates a very hostile environment for them.

“Many, including very senior members, have walked away from that lifestyle because of this.’’

Mr Duval said the value of national initiatives targeting the gangs, such as Operation Morpheus that involves multiple agencies working together, could not be underestimated.

“No state wanted to see the violence, the criminality attached to OMCGs, survive,’’ he said.

“There are still some states that probably do not have the full suite of legislation we have and that does leave them a little bit exposed, but it wasn’t hard to get agreement from all police jurisdictions to say we need to do something collectively.’’

Mr Duval signalled that the move offshore by many bikies may receive some legislative attention in future to further combat their activities.

“The fact they need to move offshore to operate has to say something about the level of disruption we have provided to their business model,’’ he said.

“The senior executives are to some degree operating the clubs, but not onshore anymore because it is too dangerous for them.’’

TAMING THE BIKIES — CHAOS TO CALM

It is somewhat ironic that the actions of just two pumped up, junior Finks bikie gang members would alter the landscape for SA’s entire bikie population.

And it is even more ironic their actions would ultimately lead to the extinction of their gang – which had morphed into the Mongols – a just over a decade later.

When the pair opened fire on a group of rival Rebels bikies in the carpark of the Tonic nightclub in Light Square in the early hours of Saturday, June 2 2007, they lit the fuse.

The Tonic nightclub shooting, which left four Rebels with gunshot wounds, was the catalyst for a seismic change.

Not only would it galvanise public opinion against the bikies violent reign of terror across Adelaide on an almost nightly basis, but it served the jolt the state government into action to implement an unprecedented legislative arsenal to combat them.

And unfortunately for the bikies, it also hardened the resolve of police. The Tonic shootout resulted in the establishment of a full-time, fully equipped anti-bikie unit, the Crime Gangs Task Force, in 2008. It took over from Operation Avatar, which had been an understaffed operation that relied on seconding detectives from various CIB units as demand dictated.

There is little doubt that over the past decade the strong suite of legislative tools and the constant, unrelenting pressure from the CGTF has had a major impact on SA’s bikie population.

A decade ago there were 308 members spread across 10 gangs. Today that number has dwindled just over 200. Late last year gang numbers dipped to their lowest ever at 196.

Crucially, the actions of police have eliminated three violent gangs in SA – the Mongols, Nomads and the Bandidos.

The Nomads were wiped out with just one operation in 2015. All 13 members were charged with offences ranging from kidnapping to blackmail – extinguishing the fledgling gang’s presence in SA.

Relentless police pressure – coupled with the surgical deportation of secretary Andrew Stevens that left president Andrew Majchrak struggling to maintain club discipline - resulted in the Mongols being eradicated in SA. It was one of the largest gangs in the state with 56 members following the patch over from the Finks in 2013.

Today, just seven gangs remain with the Hells Angels – with 64 members across three chapters – the largest.

A veteran police officer, who asked only to be identified as Detective Smith because of his current role in SAPOL, recalled this week how the Tonic shootout was the catalyst for the measures that have now made SA a hostile and unforgiving environment for gang members.

“There had been other incidents leading up to this, but Tonic was the straw that broke the camel’s back,’’ Det. Smith, who was a founding member of the CGTF, said.

“It sharpened everyone’s resolve. The public had had enough, the government knew it had to do something and we were ready. It was clear that just locking them up time and time again for individual offending was not going to solve the problem they had become.

“A lot of effort went into a legislative model, a framework to target both the group and the individual.

“It was controversial, but the controversy suited the times. There was a massive public outcry over the fact these blokes could walk down any street, enter hotels and public places and commit violent crime.’’

Det. Smith, who spent a decade in CGTF, said the attitude of the courts at the time was not helping. Little notice was paid to gang membership and magistrates had a “so what’’ attitude. That too has now changed.

“There was no resonance with the court when they appeared charged with violent offending,’’ he said.

“Now, it is one of the first things a court will ask – has this person got links to organised crime, has this person got links to an OMCG and that will be reflected in bail decisions and sentencing considerations because of the new legislation.

“That has been one of the most significant things that have come out of this whole experience.’’

Det. Smith said the reality the landscape was about to change for gang members was when the first round of the Serious and Organised Crime and Control Act passed parliament a year after the Tonic shootout.

It resulted in the hierarchy of each gang coming together for the first time. An uneasy truce between warring rivals was called and manifested in the United Motorcycle Council. Funded by each gang, the UMC did its share of political lobbying and also sought out sympathetic media figures to push its case in the public arena. It also poured its cash into the successful Supreme Court and High Court actions that defeated the first round of legislation.

One of its key spokesmen was former Finks sergeant-at-arms Mick McPherson. He professed the myths about bikies being violent drug dealers were just that. Pity his own actions were in contrast to his words. In 2012 he was shot in the stomach during a drug deal in his luxury penthouse in Melbourne, where he had shifted to. In 2016 he died in Thailand after being rundown while riding his scooter. He moved there following his shooting.

While the SOCCA had teething problems, once it had been amended to ensure it would survive any further challenges, the landscape for the gangs changed forever.

Perhaps the most crucial amendments were those prohibiting gang members from associating in public, wearing their colours and dismantling of their clubrooms. They are still the harshest in Australia.

“I think the day we took their clubrooms away, that became a slow death of OMCGs as we knew them,’’ Det. Smith said.

“They are not really bikie clubs as such, they are more organised crime groups now.

“The lifestyle that once attracted them has now gone, their public displays of bravado and overt violence are gone, the only reason they exist now in a covert form is to facilitate crime.’’

But just as the legislation and police tactics to combat the gangs has evolved, so have the gangs adapted to survive in this challenging new environment. Very much aware of the restrictions forced upon them, they have become wiser in order to survive and continue their illegal operations.

“They are very resilient, very smart. They have a business process and their uptake and use of technology is second to none,’’ Det. Smith said.

“They have evolved to work around the legislation quite well. They will also examine a judgment and pull it apart. They will look at how to get around any of those legal aspects.’’

The pressure placed on the gangs by police has also seen them struggle for membership. Once strong and respected by rivals, their need to recruit has seen standards dip as longstanding usual recruiting processes are abandoned, resulting in reduced discipline and loyalty that once existed amongst older members.

There is little doubt SA is a safer place today because of both the legislative tools and the actions of those involved in policing them. But that does not mean bikies are no longer a problem.

“The suite of legislation we have achieved is nothing short of outstanding and I do not think you will ever see the same level of overt violence again,’’ Det. Smith said.

“That is not to say we can relax, we need that continuing commitment to policing them at both a local and national level to control their illegal activities, you cannot take the pressure off.

“If you give them a little bit of latitude, they will be back.’’