Adelaide has an undeserved, erroneous reputation as the nation’s “serial killer capital”, a truthful status as a centre for bizarre crime, and a sad ongoing legacy of shocking offences committed by young people.

When two-year-old British boy Jamie Bulger was abducted and murdered by two children in 1993, horrified South Australians convinced themselves such dire events could not happen in this state.

Just three years later, Tara Maree Kehoe and Amanda Denise Pemberton tortured, stabbed and fatally bludgeoned their fellow teen, Tracy Muzyk – starting a disgraceful lineage of child crime that rapidly escalated in ferocity.

In 2014, The Advertiser predicted young offenders – like Jason Alexander Downie, Jose Omonte-Extrada and the boy known only as “B” – would be the “new villains” of Adelaide’s criminal scene, fuelled by drinking, drugs, misplaced love and directionless hate.

Six years on, that prediction has proven to be uncomfortably accurate, but not for the reasons expected.

While teenagers have continued to kill both each other and adults, the range of serious crime committed by young people now extends past murder and manslaughter.

As 2021 approaches, Adelaide’s teens are making names for themselves in large-scale drug dealing, weapons trafficking and bomb-making – and even a would-be US-style high school massacre.

THE GUN RUNNERS

On New Year’s Eve 2013, a young man named Lewis McPherson was shot and killed by a boy with whom he’d once shared a high school.

Liam Humbles would later be convicted of murder and sentenced to 24 years’ jail – but his prosecution left one key question unanswered.

Where, and how, had a couch-surfing, drunk, emotionally distressed teenager managed to get his hands on a firearm?

Australians had, since the 1996 Port Arthur Massacre, settled into the comfortable belief that illicit weapons were harder to access, that the chances of fatal shootings were near zero.

Outlaw gangs and hardened criminals somehow found weapons, of course, but that was the underworld – not the Warradale streets where Mr McPherson died.

It would take two years for the answer to emerge, and it came during the prosecution of a young man named Charles Alexander Cullen.

Months before Mr McPherson’s death, Cullen – a neighbourhood drug dealer – had given the .22 calibre pistol to Humbles, who had claimed to need protection.

But Humbles was so erratic, so uncontrollable, that Cullen demanded the weapon back.

Unbelievably, he returned it to Humbles eight weeks prior to the murder – not that he was prepared to accept any responsibility for that crime.

He insisted SA Police had to share the blame, and his stance was difficult to refute.

As revealed by The Advertiser, a whistleblower had approached police 191 days before McPherson died and warned them Humbles was armed.

“Obviously I am at fault, but if the police had done their job, then this wouldn’t have happened,” Cullen told a psychologist following his arrest.

The Coroners Court would later deem the police investigation “flawed and inadequate”, saying Humbles should have been arrested following the whistleblower’s report.

That may have vindicated Cullen’s position in the minds of some people, but District Court Judge Paul Muscat was not among their number.

“It is very disturbing that you obviously knew where to source a semiautomatic pistol,” he said when sentencing Cullen in 2014.

“You must have foreseen the possibility that Humbles would use that pistol should the need arise.

“Even worse, you were supplying a pistol to a young man who had a drug problem and who was therefore likely to be unpredictable at times.”

He jailed Cullen for eight years and called for a ban on permitting any South Australian from keeping a gun in their home.

“Many guns end up being stolen from licensed owners following break-ins to their homes, only for those guns to later end up on the streets and be used in criminal activity,” he said.

“Time and community attitudes and expectations have changed dramatically over the years – people want guns, they do not need them.”

Judge Muscat’s words were eerily prophetic as just one month later, a 17-year-old boy faced the Youth Court on firearms trafficking charges.

High on cannabis, and unable to afford more to feed his habit, he encouraged drug dealer Clifford James Schloithe to break into the family’s Semaphore home.

Inside, properly and lawfully secured in a safe, was a 33-weapon arsenal of handguns, rifles and shotguns – and 600 bullets – belonging to the teen’s father.

Schloithe, of Andrews Farm, took it all, keeping four guns for himself and selling the rest on Adelaide’s black market for a tidy profit.

The teen believed – wrongly – that he would share in the proceeds of the theft.

Instead, he received $500 and an amount of cannabis that SA Police prosecutor Zaid Farran dubbed “substantial”.

“The sheer number of firearms this boy trafficked is serious, as is the fact a number of them have not been recovered,” he told the court.

“He should have, or must have, known that these firearms were not being provided to someone who was respectable or of good character, and for illegal purposes.”

Defence counsel said the failure of the “definitely not brilliant” plan to score “quick money” had been “a huge wake-up call” to their “naive, drug-abusing” client.

Judge Stephen McEwen was more robust in his critique – of not only the boy, but also the state’s firearm laws.

“It does seem astonishing to me that (legislation) allows someone who’s not a gun dealer to congregate an armoury, really, in a suburban home,” he said.

“That lends itself to precisely the situation we have here.”

He ordered the boy serve a month’s detention and a two-year good behaviour bond.

Despite their best efforts, police were unable to recover 18 of the stolen guns.

THE DRUG TRAFFICKER

The downfall of Humbles, Cullen and the 17-year-old had demonstrated the close link between illicit drugs and illegal weapons in SA’s teen crime scene.

Three years later, in 2017, another teenager – known as “D” – faced the Youth Court on the sorts of charges traditionally filed against only the most experienced chemical kingpins.

Australian Federal Police alleged a boy, 15, had successfully imported 1kg of ecstasy into Adelaide using nothing more than Facebook and an encrypted phone app.

The sheer volume of drugs in his possession was 155 times the amount recognised, under law, as a “commercial quantity” – meaning D faced a maximum life sentence.

John Clover, for the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions, said D was the worst example of the new breed of younger, more tech-savvy drug dealer.

“Recently, another teenager imported 14g of heroin and another brought in 65g of illicit drugs,” he said.

“It’s now open for children, through the internet and other means, to operate these types of enterprises themselves.

“D was not some low-level player in a criminal hierarchy, he was the principal player in his own enterprise and was going to ultimately benefit.”

He said the evidence that had already been gathered by investigators was sufficient to back up the allegations.

“Text messages he sent during the period show him discussing the sale of drugs, specifically MDMA, and also contained a price list,” he said.

“Both packages were addressed to his home (at which) police found multiple bags of pills – with more in his vehicle – and $5000 cash and electronic scales with a residue of MDMA.”

“He performed Google searches on laundering money and where to buy 5kg of MDMA, and had an unposted Facebook status which read ‘I am a drug dealer’.”

Wisely, the Youth Court realised D’s fate was beyond its remit to offer “care, correction and guidance” to wayward teens, and agreed he should be sentenced as an adult.

D’s counsel objected, insisting their client was not a kingpin but a mule for another, adult person who had ordered the drugs.

District Court Judge Paul Rice was not prepared to accept such a submission without sworn evidence and so, in December 2017, D took the witness stand.

What followed was a short, sharp and educating shock for the community.

D revealed he had been a student at one of SA’s top private schools prior to 2016, when he dropped out due to his all-consuming drug addiction.

“It wasn’t the ecstasy that was the bad part, it was the cannabis that got me … I always needed weed,” he said.

“I took one or two ecstasy pills every three days and smoked $70 worth of weed a week.”

Dealing was, he calmly explained, the easiest way to feed his habit and earn a living – after all, kids as young as 15 were making $1000 a week selling ice and cannabis.

“I got added to a Facebook group for people selling drugs, and that helped me find drugs to buy,” he said.

“There was weed, there was ecstasy and pills, ice as well … these are private Facebook groups … people then contact you by Facebook Messenger.

“I dribbed and drabbed in selling ecstasy … I’d purchase 50 tablets or less, paying $8 a tablet, sell them for $10 each and make between $500 and $1000 a week.”

As word spread that D “was holding”, older kids and students from other schools would arrange, via app, to meet him in public parks for pick-ups.

“The police didn’t come into my head at that time … I was always high … I was so involved in the drug life that I didn’t care about my family or what I did,” he said.

“My life was drugs at that time … everything I was doing was about drugs, or better ways to get high, or famous drug dealers because everything about drugs fascinated me.”

Nonetheless, he maintained the real kingpin was an adult – one he was fully prepared to name in court, under condition of continuing anonymity.

“We met up and he told me he would offer me a sum of money to accept a package … to me that didn’t sound hard, it sounded good, it was free money,” he said.

“He said it would be drugs, I didn’t think anything of it … I thought ‘it’s just the mail, it’s fine’.

“Importing drugs into Australia isn’t of interest to me.”

The alleged involvement of an adult – and the potential for further investigations and arrests – meant D was sentenced behind closed doors and beneath the cover of suppression orders.

Judge Rice was, however, insistent one thing go on the public record.

“There’s no doubt that legally he’s a child but, in 99.9 per cent of other respects, he’s not – he’s a practised drug dealer,” he said.

THE DIARIST AND THE BLACKSMITH

There were more than a dozen knives – each one handcrafted from tools and other ordinary metal implements – on the walls of the Riverland shed.

Many hung from dedicated spots on pegboards surrounding the angle grinder and forge used to craft them.

One was much longer than the others – once a steel ruler, it was now more a machete or homemade sword – while another was unique.

It appeared to have once been a piece of metal tubing that was flattened to have a knifelike handle, but ended in a metal loop or noose.

The weapons were doubtlessly designed to inflict life-threatening damage, but other implements in the homemade arsenal were even more worrying.

Sets of “bear claws” – small blades that fit between a wearer’s fingers so that any punch would also puncture the skin – had also been crafted.

A blowpipe rested nearby, capable of firing sewing needles at high velocity.

There was, in one corner, a discarded shopping trolley that had been cut up, with two-thirds of its metal “netting” separated from its frame.

That metal wasn’t missing, it was just a few feet away – refashioned to fit around a human torso as crude body armour, secured by elasticised straps.

A piece of thick steel had been welded over the top of the netting, as if to protect the very centre of the wearer’s mass from a bullet.

These were the creations of a 16-year-old self-styled blacksmith who also liked to dabble in explosives.

Thanks to online tutelage, he had successfully brewed several batches of napalm and carefully stored them in the shed as well.

It seemed the teen was preparing to fight at extremely close range, to go down swinging and take as many people with them as possible.

And he was not alone.

Just a few kilometres away, a second boy – 18 years old – had filled two years’ worth of diaries with extremely dark thoughts.

They detailed his growing obsession with school shootings, his hatred for his fellow students and his angst over a recent, failed relationship he considered “toxic”.

Both the diarist and the blacksmith were well-known in their local community.

Riverland kids looking for a knife would go see the blacksmith – some even commissioned him to craft presents, like replica Ned Kelly helmets, for their parents.

The diarist was more infamous, and less discreet, than his friend, which saw him saddled with the nickname “school shooter” by judgmental peers.

He responded angrily and, on four occasions between June and October 2017, threatened to harm those who teased him.

The vitriol of his menace – and the detailed nature of his threats – put both the diarist and his blacksmith friend on SA Police’s radar.

As Halloween 2017 approached, the duo’s talk of massacres, of dying, of attempting to source firearms, of blowing up the school before year’s end, intensified.

When the children and teenagers of the region donned costumes for some innocent fun, the diarist and the blacksmith dressed up like the perpetrators of the Columbine Massacre.

Drunk, they headed for a car park to test the blacksmith’s latest creation – a molotov cocktail – and were extremely pleased with its effectiveness.

That prompted the blacksmith to press an older person he knew to provide him with firearms, promising payment from money he was expecting to receive through family connections.

Fearful of further escalation, Major Crime detectives – who had been watching the pair like hawks – moved in and arrested them both.

In a press conference on November 30, they shocked and horrified the entire state by alleging the duo had planned not individual retribution, but mass murder.

Their plan, they alleged, was to use the napalm to seal every student inside a Riverland high school, then kill “as many as possible” with knives, blades and guns.

Detective Superintendent Des Bray said that plan had been formulated just four days before the diarist uttered his first threat against a fellow student.

The boy had, he said, been armed when each threat was made.

“We believe most likely the attack would have occurred, if not stopped, before the end of the current school term,” he told the media.

“It’s unbelievable to think that this sort of thing could happen in SA … I am not aware of us having an incident like this in recent times,” he said.

“There is no doubt in my mind that we prevented a catastrophe.”

But those who took the side of the diarist and the blacksmith disagreed.

“My son will always help anyone who needs help, he is a fun-loving kid,” the diarist’s mother told The Advertiser after his arrest.

“He’s got a great personality … he’s no angel, even he won’t say that, but he’s not someone that everyone now perceives him to be.

“He’s not the cold-hearted psychopath that he was painted out to be.

“He wasn’t aggressive, he would have opinions but he would come back and would say what he thinks was wrong.”

One of the 18-year-old’s former friends agreed, calling him a “good kid”.

“We’d just hang out and do silly stuff, I showed him how to play instruments, we’d play games, talk about stuff,” he said.

“He used to be chill as, we’d just go walking around the streets doing normal mates stuff, but then something changed.

“He did start getting weird, he was sort of sketchy … he was always anxious and he’d say ‘I want to go home’, but he never used to be like that.”

Those sentiments were echoed by the duo’s legal counsel.

The diarist, they argued, was “all talk” and his diaries were filled with “dark fantasies, not reality” that were the subject of longtime Riverland gossip.

“The diaries that police have seized display dark themes and ideas which were really a way of him venting to cope with his environment,” lawyer Nikki Conley said.

“It was never anything he intended to act on, it was not something that was serious … it was all talk.

“He was extremely troubled by these thoughts and he wanted to stop them, but they remained vivid.”

Counsel for the blacksmith made similar suggestions, only for prosecutors to assert he was the more dangerous of the two.

They said police had real concerns that, if released on even the strictest form of home detention, he was “extremely likely” to resume his work and carry out the attack.

That was enough for the courts to agree the duo posed too great a risk to the public, deny them bail and order they be tried as adults.

The trial never eventuated, thanks to a plea bargain struck between prosecution and defence counsel.

In March 2018, the duo – originally charged with conspiracy to murder and soliciting murder – instead confessed to lesser charges.

By pleading guilty to aggravated threatening life, the boys evaded the possibility of long prison terms.

They also gave their counsel’s pleas for sympathy and understanding a strong peg from which to hang, one month later in the Supreme Court.

Bill Boucaut SC, for the diarist, urged the court to view his client as a bullied “emo” teenager who’d done no more than vent his frustrations with the world.

“He is different to what might be considered the average teenager in a country town … his peers simply regarded him as being weird,” he said.

“He was wearing dark clothing, putting on dark makeup or eyeliner … he always liked heavy music which is part of the makeup of this particular type of young person.

“The diary was his mechanism for getting back at and dealing with a fairly entrenched regime of bullying that he was subjected to during his time at school.

“The various Facebook conversations with (the blacksmith), the ramblings in his journal entries, were created at times when he was heavily intoxicated.”

Stephen Millsteed, for the blacksmith, said the duo were misfits, fellow “discontented outcasts” who were mutually “disillusioned” with life in the Riverland.

The blacksmith, he stressed, had never been bullied but wanted both he and the diarist to be seen as “people to be reckoned with” in their community.

“There’s an abundance of evidence that blacksmithing has been his hobby since the age of 14,” he told the court.

“He used various methods to maintain the heat in his shed needed to forge steel until he discovered how to make napalm.

“He found napalm was ideal for forging steel because of the intense heat it generates and the long period of time it remains flammable.

“It was in that context he made napalm, not for the purposes of causing harm to anyone.”

Mr Millsteed – himself a retired District Court judge – and Mr Boucaut them teamed to make a suggestion no one in the community saw coming.

“He should be required to serve no more time in custody, as he has already spent 18 months in detention,” he said of his client.

“Enough is enough … he should be able to go home and resume his life.”

Mr Boucaut echoed the sentiment.

“Threats of that nature are understandably going to cause significant concern in the community, and nothing I say ought to be taken as belittling that effect,” he said.

“But it has to be understood that this was nothing that was intended to be carried out.

“The period of time he’s spent in custody is long enough … I would urge the court to fashion a sentence that would enable him to be released immediately.

“He has, in my submission, done his time – well and truly.”

Such is the nature of plea bargaining that prosecutor Jim Pearce QC lent his voice to the chorus.

“They are two troubled young men who clearly lost their way, but they are going to be released sooner rather than later,” he said.

“The court ought to give earnest consideration to not just releasing them, but to placing them under supervision.

“They need ongoing assistance, rather than being left to their own devices to fall back into unwanted behaviour.”

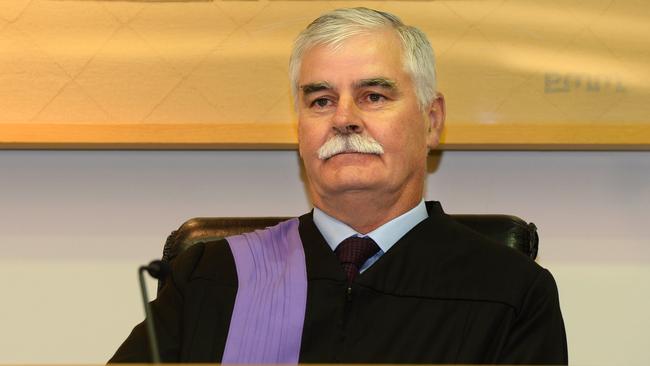

One month later, Justice Kevin Nicholson agreed that immediate release was the appropriate course.

In sentencing, he mourned the duo’s “very sad and dysfunctional” upbringings, which had robbed them of the chance to “develop to your full potential”.

“Your plan was to frighten, to terrify, to present yourselves as ‘school shooters’ who meant business and were to be reckoned with,” he said.

“I’m satisfied that once you started to conceive of your plan, you jointly contributed to the creation of that plan – albeit, as it turned out to be, a fantasy.

He praised the diarist’s expressions of “remorse, guilt and empathy” as well as the blacksmith’s “capacity” for leadership, displayed while in detention.

Taking into account time served, he sentenced the diarist to six months and 21 days’ jail, and the blacksmith to six months and 19 days’ jail.

Both sentences were suspended on condition of three-year, $500 good behaviour bonds – meaning they could be immediately released from custody.

“You are both bedevilled by factors which, experience suggests, predispose a person to criminal conduct (including) a deep-seated hostility to your community,” Justice Nicholson said.

“This makes it difficult to assess how you will conduct yourselves in the future.

“However, both of you show insight into the wrongfulness of your conduct and the harm it has caused so many people, and expressed real desire to better yourselves and not do such terrible things again.”