FOR two decades, Henry Keogh was in jail as one of SA’s most reviled murderers. But journalist Graham Archer kept questioning the official narrative ... and eventually Keogh was cleared. In his own words, Archer recounts the clues and contradictions that led to a wrongful conviction.

AS nature abhors a vacuum, so humans abhor a mystery. Our desire for answers is insatiable. In the absence of obvious solutions we are sometimes tempted, or driven, to speculation, even fabrication. It’s this need that gives life to conspiracy theories.

The drive is stronger if the enigma involves loss, and more powerful still if that loss is of a loved one. Not only do we hate the absence of cause, we seek to lay blame. The victim must be freed from the responsibility of their own misfortune.

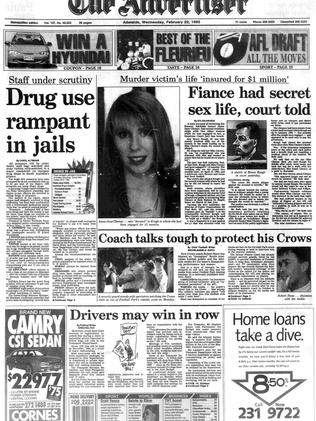

The death of 29-year-old lawyer Anna-Jane Cheney on March 18 1994, six weeks before her wedding to fiance Henry Keogh, is one such mystery.

Keogh’s conviction for Anna-Jane’s murder was quashed in December 2014, but the shadow of guilt remains.

The Full Bench of the Supreme Court stopped short of an acquittal.

Their 119-page judgment left the noose swinging with just a couple of lines: “ … we consider that the non-expert circumstantial evidence, when considered together with the forensic pathology evidence as it is now understood, is such that it would remain open to a properly directed jury to convict”.

It’s a curious supposition considering they hadn’t examined any circumstantial evidence.

All the eminent experts, including the Crown’s, opted for a diagnosis of accidental death.

Nevertheless the Full Court’s assertion has left Keogh in legal limbo.

His predicament exacerbated by the Director of Public Prosecutions’ decision not to put the “other” evidence to the test.

The Marshall Government’s grant of a $2.57 million ex-gratia payment to Keogh had shadow attorney-general Kyam Maher spotting a political opportunity.

He’s called for the Budget and Finance Committee, which he chairs, to examine the payment process.

It inevitably reactivated the Full Court’s caveat on Keogh’s redemption. Putting the politics aside, what would a “properly directed” jury have before it?

Regardless of the flawed forensics, many still see the motives of greed and betrayal as the simplest way to resolve the tragedy of Anna-Jane’s death.

These things we can understand. But if they are so compelling, why did the order of the court for a retrial languish?

Many South Australians know the basic tale — how Anna-Jane’s fiance Henry Vincent Keogh found her lifeless body in the bath, and quickly became the prime suspect for her murder.

The attractive, private-school-educated Anna-Jane worked at the heart of Adelaide’s exclusive legal establishment.

She was known to some as the “baby boss” because of her youth, and would skip and bounce her way around the office when in a buoyant mood.

She was popular among her male counterparts in the profession but largely found them dull and complacent.

She once told her mother: “I can sit at a dinner table and look at my lawyer friends and think ‘You slept with him, and he slept with her and so on … it’s so incestuous. I’m not like that, I don’t want that for myself.”

Henry Keogh was different. Quick-witted, worldly, well-read and reflective.

He offered her a vision broader than the suffocating smugness of her peers.

Being 10 years her senior and a divorced father of three daughters from Irish Catholic stock did not endear him to Anna-Jane’s parents.

Her mother, Joanna, was openly hostile and threatened not to attend their wedding.

Anna-Jane’s brother Marc, a salesman of prestige motor vehicles, was also not well disposed towards Henry. The somewhat dour sibling considered him to be glib and offhand.

Anna-Jane appeared to relish the fact that Henry had the power to free her from the possessive clutches of her mother.

Her father Dr Kevin Cheney, a haematologist working for the Crown, was a more compliant figure.

Unfortunately the personal dynamics were volatile should anything go wrong. Clearly it did.

It’s now history that in August 1995, after two trials, Keogh was convicted of the drowning murder of Anna-Jane.

History too, that in December 2014 the Full Bench of the Supreme Court overthrew the conviction on the basis of the flawed forensic evidence.

In a nutshell, the only physical evidence to suggest Anna-Jane’s death at the hands of another was found to be false.

It is an enormous and as yet unplumbed scandal that the State’s Senior Director of Forensic Pathology was unqualified to do his job.

Many of his pronouncements over almost 30 years were erroneous. Keogh was just one of many to suffer for his incompetence.

In this case he provided two juries with incriminating evidence that he knew, at the time, not to be true.

His fictional scenario had Henry scooping up Anna-Jane’s legs while she was in the bath and forcing them over her head. It was based on a lie.

In fact it was the obvious lack of injury, to both Henry and Anna-Jane, which led every one of the 11 police officers and paramedics who attended the scene to consider it an unsuspicious death.

However, there was one other unqualified exception.

Constable Patricia Walkley drove the coroner’s van to the Magill home on the night of Anna-Jane’s death.

She was a robust woman who had been with the Forensic Science Centre for 11 years.

Her principal task was to convey bodies to the morgue and assist with post-mortems, even though she had no formal skills in this area.

Her only contact with Keogh had been to ask him to leave the room while she took it upon herself to inspect the body.

In that brief moment she appeared to pick up on the contempt Joanna Cheney felt for her future son-in-law.

Forty-eight hours after Anna-Jane’s death, Walkley entered into the coroner’s running sheets that the “whole family hated Henry Keogh”.

Her jottings included the Cheneys’ suspicions about insurance together with pejorative observations such as: “He is VERY possessive of her — he says he’s a managing director but no one really knows what he does.”

It was these musings, subjective as they may have been, that were sufficient to have Dr Colin Manock, the forensic pathologist, return to the mortuary a second time, having originally found nothing amiss, and “discover” his nefarious “grip mark”.

It was the smoking gun that sealed Keogh’s fate.

Despite the exposure of the forensic falsehoods in the 2014 appeal, the “girlfriends” and the insurance policies — with the implications that Keogh kept them “secret” and “lied” about them — still hovers over this case.

It is the default position for all who can’t accept the system could fail.

It is also the default position for all those who must find an answer which satisfies the need for someone to blame. The question to pose is whether we reinterpret events to coincide with the answer we are seeking?

The term “tomb-stoning” is not in common usage but it is well known in the insurance industry.

It refers to the practice of writing bogus policies against people who may already be deceased in order to show sales activity.

The premiums in the first few years are more than offset by the commissions.

While this conduct amounts to fraud, it was quite prolific — particularly among those beginning a sales career in insurance.

It is well nigh impossible to get anyone to state on the record that it has been common practice.

Keogh worked for the State Bank in the early 90s when it was near to collapse, having lost $4 billion of taxpayer-guaranteed funds.

While a Royal Commission picked over the carcass, the employees feared for their jobs.

Keogh’s area of expertise was in the private banking sector where he tended to the financial needs of individual clients.

He saw a future in financial advising and undertook part-time study to help pave the way.

Insurance is an important component of financial security.

During the trials, his former wife Sue explained they had a company called Keogh Investment Services and he had worked briefly as an insurance agent before joining the State Bank.

He had agencies with five insurance companies and put a number of policies through those accounts, including personal insurance for himself and his family.

When asked about him signing her name on such documents, Sue Keogh replied: “Yes, we had an understanding he could do that.”

The day after Anna-Jane’s death, Henry Keogh was described, by all who saw him, as a complete “mess”.

A bank colleague who came to comfort him asked about Anna-Jane’s mortgage protection insurance.

She recounted the conversation as him saying he could not recall her having any.

Twenty-four hours later, Keogh visited the Cheney family home and Anna-Jane’s father quizzed him about her insurance.

Again Henry was vague about the state of her finances. It was these two conversations, in the midst of shock and grief, which would haunt him forever.

Twelve month’s prior to Anna-Jane’s death, Henry had created seven policies through his agencies.

Two were on his own life with Anna-Jane as the beneficiary, and five were over her life.

The latter totalled $1.15 million dollars. As he had done with his ex-wife, on each policy application he’d forged Anna-Jane’s signature.

This was, according to Keogh, his venture into “tomb-stoning”.

The plan was to keep his agencies active while he decided the direction of his career.

As long as the commission and the premiums were roughly equal there was no “victim” in this practice, though it was technically fraud.

He maintained Anna-Jane, as a legal practitioner, chose not to be involved.

The sums assured on each policy were below the level that required her to undergo medical examinations.

This was interpreted as part of his plot to ensure she had no idea of their existence.

Paul Rofe QC, the gruff Director of Public Prosecutions, informed the first trial jury that all of this was part of a secret conspiracy, enacted over 12 months, and “if he (Keogh) lied about the insurance policies … he has murdered his fiance to claim on those policies. The motive is simply money.”

Everything associated with the insurance could be interpreted as entirely innocent or as part of a fiendish plot. If it was a plot, as Paul Rofe maintained, “premeditated and meticulously planned”, the version he put to the juries glossed over some of the obvious imperfections.

Two of the policy premiums were paid through a joint account so Anna-Jane was unlikely to have been oblivious to their existence.

Both her brother Marc and father Kevin confirmed she’d told them of having at least $400,000 in life insurance.

This must have been part of the total from the “secret” policies. If she was aware such policies existed she must also have known, like Sue Keogh before her, that Henry had taken care of these matters and had signed her name.

In November 1993, Anna-Jane applied for a bank loan to purchase a car.

In March 1994, she extended the loan to upgrade the vehicle to a Volvo supplied by her brother. On both loan documents she accounted for weekly outgoings of $36 for “life insurance”.

It was precisely her share of the premiums covering the five bogus policies.

By this stage she was the Acting Director of Professional Conduct and Practice at the Law Society and unlikely to want to mislead a bank on any formal documents.

If she knew the policies existed, accepted them as part of her financial obligations, the “scheme” could not have been hatched in secret.

There aren’t too many among us who don’t have a financial stake in the lives of those close to us. It doesn’t make us potential murderers.

Nevertheless, Keogh had put himself in an awkward situation, which would have passed unnoticed but for the untimely death of his fiance.

The dilemma he faced was this: Did he admit to the existence of policies, knowing they were fraudulent, or did he claim there was no insurance and avoid awkward questions?

The second option, he may have reasoned, was not really a “lie”, because the policies were actually bogus, merely serving a collateral purpose.

Five days after Anna-Jane’s death he handed three of the policies, worth about $625,000, over to the police.

A week later he found the remaining two policies, which had been filed separately.

By this time he had engaged a lawyer and took advice to provide the documents to him.

They were then supplied to police. The prosecution claimed Keogh was deliberately feigning, seeking to hold back the number of policies in the hope of reducing suspicion. It’s a moot point.

The idea of killing someone for $625,000 rather than $1 million seems a trifle academic.

Eight weeks after he was charged with murder, the Cheney family petitioned the court to have Keogh removed as executor and ultimately beneficiary of the Anna-Jane’s will.

It was a public excommunication and one of many things which undermined his entitlement to the presumption of innocence.

In truth it’s a nicety which immediately becomes a myth once the police have an accused in their sights. And then comes those women.

Once again Constable Patricia Walkley had something to contribute to Keogh’s downfall on the subject of relationships.

Included in the Coroner’s notes she had written: “Deceased had broken up with fiance several times and had gone back to him.”

In the context of the other things Walkley had noted down, the implication was damaging.

Keogh was characterised as difficult and unreliable. It’s not unusual for relationships to have their ups and down and this one had its share.

In fact it helps explain the presence of other women on the scene.

One of the stress points was that Anna-Jane may have wanted children and he definitely did not. After his third daughter was born, Keogh had a vasectomy.

In the end, according to Keogh, Anna-Jane assured him she was only interested in her career but he expressed concern she might regret that decision.

Following their breakup in March 1993, two women did become more prominent in his life.

Though the defence argued the women’s testimony added nothing to the question of murder, its sensational and salacious nature added immeasurably to the prejudice felt towards Keogh the man.

The identities of both women are still suppressed.

The first of them was a girl about town. She’d had numerous relationships and was emotionally robust.

She and Henry Keogh became involved in July 1993, three months after he had split with Anna-Jane.

The casual relationship continued until December of that year and marginally overlapped with Keogh’s reconciliation with Anna-Jane.

He made no attempts to deny or diminish this interlude.

The second woman was mentally unstable. She had been a banking colleague whom Keogh foolishly attempted to support.

It was to be a dangerous liaison. By the time she gave evidence she had been on stress or sick leave for around 15 months.

It emerged she had lodged around 20 sexual harassment claims against fellow staff including senior management.

None of these had been upheld. Her evidence that she had a sexual relationship with Keogh was hotly disputed.

The most sensational evidence came when she was asked if Keogh was circumcised. She said “yes”, the answer was “no”.

The court however was transfixed throughout her time in the witness box, which culminated with her defiant challenge to the packed courtroom over the circumcision question: “No one stares constantly at a penis for an hour or half an hour. I don’t think anyone in here would stare at a penis for that long, just look at it.”

The court remained silent.

In contrast, throughout the trials, Anna-Jane’s personal life remained a closed book.

Understandably the defence did not want to alienate the jury by criticising the “victim”.

What emerged many years later in the course of other hearings were greater details of Anna-Jane’s medical records.

There were a number of interesting developments, but one in particular has relevance to the period Henry and Anna-Jane had separated.

One of her Medicare item numbers identified as a pregnancy test.

Considering Henry had undergone a vasectomy, he can’t have been a candidate.

Is it possible that Anna-Jane had enjoyed relationships of her own during that time?

What is sauce for the goose, as they say. This also contrasts with Kevin Cheney’s image of his daughter.

In his witness statement he said: “I don’t know if their relationship was an intimate one. Anna had always said she would not sleep with anyone until she was married.”

We often see what we want to see, despite the intimate complexities of human behaviour.

The matter of insurance was also not yet finished, despite it having been proposed by the prosecution as the motive for Anna-Jane’s murder.

In March 2000, the administrator of Anna-Jane’s estate sued the five insurance companies for the $400,000 cover she had mentioned to her brother and father.

They argued that the companies were responsible for the fraudulent conduct of their agent, Henry Keogh.

In October the matter was settled by conciliation and the family, as the beneficiaries of the estate, collected the proceeds.

Their entitlement to that payment, and their status in the will, may now have changed following the quashing of the murder conviction.

It could be the subject of some awkwardness if they accepted that Henry Keogh was no longer a murderer.

Constable Patricia Walkley too had not finished with the case. Twenty years after his conviction when Keogh had the chance of an appeal, Walkley — by then retired — rang the current DPP’s office and offered herself as a witness for the prosecution in challenging Keogh’s appeal.

She became the only witness the Crown called, aside from a Melbourne forensic pathologist Dr Matthew Lynch, who agreed with the defence that Dr Manock’s “grip” theory of murder was unsustainable.

Pointedly, neither Dr Manock, nor his former deputy Dr Ross James, who supported the theory even after the emergence of evidence to the contrary, were called upon to give evidence.

When Walkley was sworn in as a witness, she said she’d seen something on TV about the case that was incorrect but couldn’t remember what it was.

She thought it could be something to do with the bruises on Anna-Jane’s leg.

She admitted she had merely attended the scene to collect the body but she took it on herself to be observant. What followed was quite bizarre.

She told the court she remembered not seeing any soap in the bathroom and “being a female I’d be wanting to have a flannel or soap or have a wash or soap, or that sort of thing; it’s just an observation”.

The implication being the Anna-Jane had somehow been forced to take a bath.

Walkley was then shown a photo taken by police of the bathroom on that night and there was a Body Shop bottle of bath salts, next to the bath.

She was also reminded that in her original witness statement she had noted that Anna-Jane’s hair smelled of shampoo.

The questioning revealed Walkley had no qualifications to make any observations about the body, nor any expertise to offer commentary on what might have happened.

This hadn’t stopped her speculations which encouraged Dr Manock to concoct his “grip” theory.

What is most remarkable is that the DPP actually called her as a witness in the appeal when she demonstrated herself to be so unreliable.

Following the Full Court’s order for a retrial, the prosecution spent almost 12 months during which the DPP, Adam Kimber SC, considered his option for re-prosecuting Keogh.

He had at his disposal all the resources of the state.

Curiously at no stage during the numerous directions hearings did the DPP raise the topic of the insurance or the “scarlet women”.

In September 2015, Justice Blue asked the Crown’s most senior prosecutor “would the prosecution be knocked out if you couldn’t prove the post-mortem?” The reply: “It well may be your Honour. It well may be, yes.” And so it was.

Oddly enough it all swung on the presence of Dr Manock, not called during the appeal. The probative value of the “other evidence” appears to have been zero.

When Police Commissioner Grant Stevens appeared before the Budget and Finance Committee hearing recently, he said calling Keogh “a person of interest” was “an understatement”.

What evidence does he have for that? Since the quashing of the conviction have the police conducted a fresh investigation?

Unlikely, because no witnesses have been reinterviewed. Has SA Police re-examined the forensics and arrived at an alternative conclusion? Almost certainly not.

Has he considered the findings of all the expert witnesses and decided for himself they are wrong?

Is the Commissioner’s view coloured by the residue from two unfair trials and the Full Court’s unwillingness to sign off on the Crown’s culpability in a miscarriage of justice?

Is Henry Keogh to be forever held hostage by a judgment that didn’t judge all of the evidence?

Whatever the answers, there’s precious little he can do about it.

As they say, everyone is entitled to their opinions, but opinions only have weight if they are informed, not subjective or speculative.

That’s the test we ought to apply in all cases. It’s a case of “put up or shut up”. It appears our authorities can do neither.

The one fact we are all obliged to accept is that we weren’t there.

Graham Archer is an author and former Channel 7 Adelaide news and current affairs director. His book Unmaking a Murder was judged Best True Crime book of the year in the 2018 Ned Kelly Awards.

‘I miss being able to talk to them’: Tribute for slain Aussie brothers

A tribute has been unveiled where Australian brothers Jake and Callum Robinson and their American friend were murdered during a surf trip.

Melb private schoolboy’s stunning Russian mafia admission

An investigation into former Melbourne private schoolboy Damien Carew has taken a dramatic turn after his latest police confession.