How an Aussie invention forever changed how police across the world view crime scenes

YOU know it from TV shows such as CSI — but it was actually a small group of Australian scientists who changed the way police forces around the world view scenes of crime.

THEY may have never made a direct arrest and you’ll never have heard their names.

But 40 years ago, a small team of Aussie police scientists had an idea for an invention that would become world famous, revolutionise crime scene analysis and indirectly solve countless crimes globally.

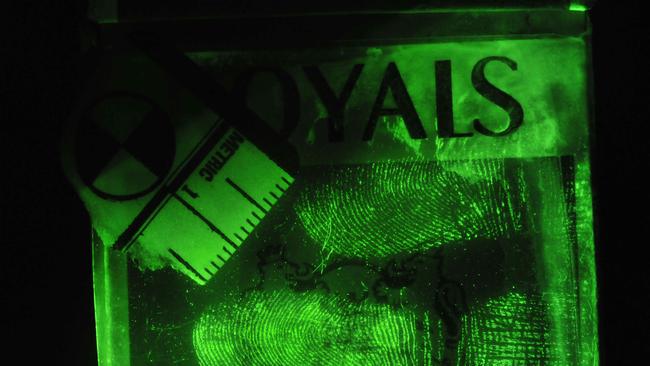

Most police officers today won’t even remember a time before the 1989 introduction of Polilight technology, with the device now used on 98 per cent of all crime scenes to throw up otherwise invisible to the naked eye evidence of bodily fluids and blood splatter stains, fingerprints and forgeries.

As seen on TV shows such as CSI: Crime Scene Investigations, Dexter and Bones, it’s standard now to see forensic officers with the portable UV light box revealing crime scene evidence.

It’s impact on modern day crime fighting has been so great the device is often cited as one of the greatest Australian inventions of the 20th century.

All in the mind: The hypnotist helping crack major crimes

Who’s who: The stories behind famous criminal nicknames

Before its development, dusting for prints was seen as the best technique to gather critical evidence and catch a crim, but the journey of the technology began in the late 1970s, with the Australian Federal Police’s Scientific Research Directorate and the Australian National University joining forces to see what more they could reveal using lasers.

The AFP directorate’s director Dr Malcolm Hall had visited forensic science laboratories in the UK, US and Germany and knew there was potential. He began assembling a team and sourcing funding for what he envisaged would be a world-first crime-fighting tool.

“The need for improved fingerprint practices and outcomes, along with emerging technologies, encouraged me to initiate a scientifically-based research project on fingerprint enhancement,” Dr Hall told the AFP’s internal newsletter Platypus this month.

“In my opinion, the resulting benefits have been outstanding and reflect positively on the AFP in its preparedness to financially support scientific research.

“Without the establishment of the Fingerprint Research Unit at the ANU, when combined with the research outcomes from the Unit as a whole, the concept of a portable light source would not have been realised. Today, it serves as an important tool in crime scene investigations throughout the world.”

In early 1980, Dr Hall approached Professor Ron Warrener, head of the ANU’s Department of Chemistry to see if he would be interested in setting up a Fingerprint Research Unit with funding from the then newly-created AFP national force. In that same year they were joined by two Australian migrants, former Yugoslav physicist Milutin Stoilovic, and Dr Hilton Kobus, who had been the Director of the Zimbabwe Police Forensic Science Laboratory. Chris Lennard, a PhD student in chemistry, then joined the team, as did Lausanne University’s Pierre Margot.

“No-one knew what this new light source would look like, it really was a blank canvas,” Mr Stoilovic, 77, said of the excitement of the early challenge.

While Lennard and Kobus focused on the chemistry of fingerprints themselves, resulting in the development of a range of novel techniques for making fingerprints visible, the others began looking at laser applications and the creation of a lamp — at that point christened the Unilight — to better see the amino acids which are secreted from pores in the fingerprint ridges.

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook and Twitter

The team compared many light sources, and while laser technology was being chosen elsewhere for fingerprint enhancement, it had practical limitations, including the fact that it was large and its light source was so strong that if a fingerprint was present on a surface, the background fluorescence often swamped any light coming from the fingerprint, making it difficult to see.

“Further, the laser light was restricted to a few spectral wavelengths, whereas it was possible with the lamp, as a white-light source, along with a series of filters, to produce a wide range of spectra,” Dr Hall said.

The next challenge was to make the bench-based lamp portable and it was Stoilovic and his knowledge of optics that overcame this challenge.

A prototype was soon developed and using the ANU’s commercial arm, Anutech Pty Ltd, the concept was sold to Rofin Australia Pty Ltd. The Polilight was born.

It has gone on to be used in almost 100 countries around the world — notably by the FBI and CIA in the US and Scotland Yard in the UK — and is seen as an essential investigative and intelligence tool.

The AFP’s Chief Forensic Scientist, Dr Sarah Benson, said the invention of Polilight was revolutionary and remained a proud achievement for the AFP.

“In its day it was certainly cutting edge technology … it brought a whole new dimension for how we approached crime scenes and our ability to collect fingerprints in the field,” she said.

“It certainly gave us the ability to make significantly more identifications where otherwise people wouldn’t have been identified, and previously would have got away with the crimes they committed.”