How AFP, Colombian cops found cocaine worth $1 billion before Dairo Antonio Úsuga’s arrest

This is how the AFP and Colombian law enforcement and military officers found $1 billion of cocaine in the jungle just weeks before the world’s modern day Pablo Escobar was arrested.

Behind the Scenes

Don't miss out on the headlines from Behind the Scenes. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Armed with guns, machetes and trained dogs, they began their wild hike through the Amazonian jungle in the dead of night. They needed darkness to get the edge on the armed guerrilla and deadly narco-paramilitary groups threatening their covert mission.

Just like the movies, the reconnaissance team was travelling ahead, slashing their way through the thick growth. With the dogs sniffing for landmines and camouflaged IEDs, the team edged closer to their target – a stockpile of drug chemicals capable of cooking up $1 billion worth of cocaine.

For three long days and two nights the group of Australia Federal Police and Colombian law enforcement and military officers hiked slowly and maintained complete silence for fear of alerting lookouts for the dangerous drug cartels controlling this savage and deadly region of Colombia.

They had lay up points and specific breaks so the forward scouts didn’t get too tired and make a deadly slip up.

“It becomes dangerous if the reconnaissance group is too tired to see what is there,” a senior AFP officer said.

“It is not a successful mission if someone steps on a landmine on the way out.

“They know there is no guarantee you will come out. Not all missions are successful – people can still die,” he said.

The jungle air was hot and humid and the team had to be able to move quickly as they safely could given the dangers.

So the group carried very little. Just enough food and water to get through – enabling them to act fast should they be ambushed. They had the backup of the Colombian army and the navy offshore, but if something happened on the ground they had to take care of themselves.

It was nerve-racking trying to avoid landmines, hidden booby-traps and their trigger mechanisms some attached to foliage overhead which doubled as aerial camouflage from police and military surveillance.

This area of the thick, green, jungle on the Pacific Coast not far from the port of the poor but busy port of Buenaventura, is where people go missing, are shot on sight or are taken hostage only to turn up tortured and murdered.

Three main guerrilla groups “rule” this lawless area. The feared Golfo Clan headed by the notorious and now captured drug trafficker Ontoniel, the ELN (the guerillas of the leftist National Liberation Army), and a splinter group of the FARC dissidents known as Jaime Martinez.

Power structures and alliances are so fluid and shift between the groups it doubles the element of danger and it is difficult to know who is in charge any particular moment.

Intelligence had led the international police team named Operation Basilisk on this highly dangerous mission to seek and destroy a huge stash of cocaine precursor chemicals being used as a supply depot by drug cartel cooks.

Police believe this stockpile was being held away from the drug kitchens and compounds just in case they are raided by law enforcement.

“Then the cooks can come and take what they need and they don’t lose all their chemicals at once,” the agent said.

After three days, in an inaccessible and remote location, the team finally found what they were looking for – barrels of the drug stash. It was camouflaged from above and surrounded by booby traps.

Six large barrels containing approximately 1300 litres of precursor chemicals - enough to flood $1 billion of cocaine on the streets in Australia.

There were no lookouts at the chemical sites but they were aware of general spies in the area watching for any police or military snooping around and they had seen people in the distance.

“They were using people to walk around while they went about their business and keep a lookout in the vicinity.”

The location of the chemicals is quite difficult to get at.

The barrels were not labelled or marked with any cartel signature as are drug bricks and pills.

“They don’t label their chemicals – there is no need to label them. Everyone knows who they belong to and no-one is going to touch them or steal them,” the agent said.

“There is no need to label things in your own home.”

They later discovered the stash belonged to the Jaime Martinez cartel.

With such a large amount it was way too dangerous to try and transport the drugs out of the jungle with the threat of the armed criminal groups and landmines. So the chemicals were destroyed on site under the supervision of an environmental scientist.

Alarming intel from their scouts came in just as they were disposing of the chemicals. An armed group of guerillas was just 20 minutes away on the move and would soon intercept them.

Time was ticking as to how long they could stay at the site.

“The adrenaline was pumping and they had to leave ASAP so as not to give them time to set up an ambush on the way out,” the AFP agent said.

“The way out is more dangerous than the way in. Because everyone was so hot blooded, (there was concern) they might step on a landmine without looking,” he said.

“There was a feeling there were not out until they were completely out of the jungle.”

MODERN DAY PABLO ESCOBAR NABBED

He is the head of a cartel almost solely responsible for the cocaine flooding Australian cities, but most Australians have never even heard of him.

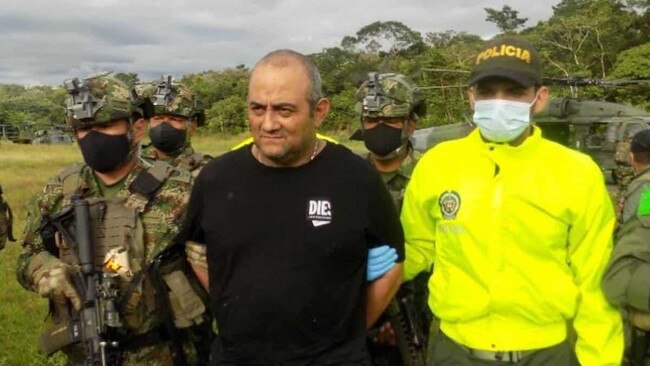

Drug lord Dairo Antonio Úsuga has been dubbed the modern day Pablo Escobar – the King of Cocaine – for the amount of cocaine his crime gang has smuggled around the world including Australia.

Known locally as Otoniel, which means powerful lord in Spanish, the 51-year old had a $5 million bounty on his head as the world’s most dangerous drug trafficker and head of the Clan del Golfo.

That was until he was finally captured in October last year after a seven year manhunt – just weeks after jungle raids by Australian Federal Police and Colombian law enforcement which uncovered tonnes of cocaine precursor drugs in a remote jungle area on Colombia’s Pacific Coast.

Otoniel was arrested in a dramatic sting operation in the remote Antioquia province involving 500 soldiers and 22 helicopters. One police officer died in the operation.

Colombia produces the majority of the world’s cocaine and drug data from the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC) shows more than 70 per cent of all cocaine seizures in Australia came from Colombia.

The Clan del Golfo, or the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, is largely made up of former far-right paramilitaries who returned to lives of crime after a peace agreement with the government.

It is responsible for trafficking between 180 and 200 tonnes of cocaine a year, according to Colombian authorities and is the country’s largest drug cartel.

But the clan is battling the guerillas of the leftist National Liberation Army (ELN) and also the Organized Armed Group, GAO-r known as the Jaime Martinez structure, for control of the drugs and smuggling routes.

It controls many of the routes used to smuggle drugs from Colombia to the US and the rest of the world. Law enforcement have described the clan as “heavily armed and extremely violent”.

Clan members launched a bloody wave of retaliation after Otoniel was arrested murdering about 20 police officers and holding almost half of the country to ransom by imposing curfews, closing down business and blocking streets.

General Jorge Luis Vargas, the director of the Colombian national police said the Clan del Golfo does business with five mafias groups and international cartels including the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco Nueva Generacion cartel in Mexico and the Calabrese and Sicilian mafias in Italy and the Balkan networks.

General Vargas said Otoniel was sending cocaine to 28 countries including Australia sent through the US, Belgium, Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Ireland, the United Kingdom, Italy, Albania and Ukraine.

More Coverage

Originally published as How AFP, Colombian cops found cocaine worth $1 billion before Dairo Antonio Úsuga’s arrest