How our favourite drinks depend on the mystery of fermentation

WE wouldn’t have wine, beer or spirits without it.

delicious SA

Don't miss out on the headlines from delicious SA. Followed categories will be added to My News.

FANCY a wine, beer, cider, gin, rum, vodka or whisky? Fermentation is the number one secret to all these things delicious and drinkable.

That’s because the alcohol at the core of your preferred tipple is the result of the conversion of fruit or grain sugars into ethanol (plus carbon dioxide).

That’s enough basic science for now, except for the sourcing of those sugars. Wine from grapes. Cider from apples or pears. Beer from grains like barley or wheat. And the spirits distilled from alcohol fermented from a range of grape, grain and other vegetables — rum, for instance, starts out as sugar cane.

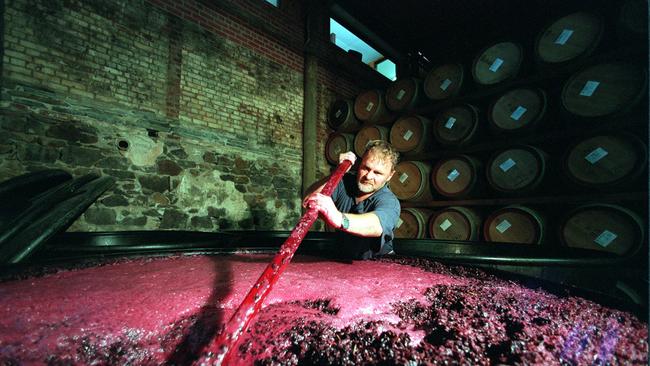

Winemakers live and breathe their ferments, essentially the process where the grapes are brought into a winery (or shed, if it’s a tiny artisan operation), the fruit either crushed or pressed a bit to liberate the juice, and yeasts are either introduced or allowed to spontaneously develop to begin converting the grape sugars to alcohol.

You’ll hear many modern winemakers extolling the virtues of the widespread trend to let their grapes, red or white, undergo what’s called “wild fermentation”.

You may also see on labels a reference to “indigenous yeasts”, the essential kick-starters that exist on the skins of grapes or a floating around the winery that slowly begin to develop a wild fermentation, increasingly favoured as producers explore hands-off techniques and argue that the results in more complex aromas, flavours and textures.

Sometimes the results aren’t all good, but that’s where trained and more experienced winemakers step in and take control to prevent the nasties occurring, which can result in faulty wines.

Deviation Road winemaker Kate Laurie says fermentation is as much about preventing the wrongs as encouraging the rights to end up putting a wine on the table that is firstly palatable and preferably really nice to drink.

“It’s the biggest tool we have got,” Kate says.

“The choices we can make from yeast strains or wild yeasts, to using secondary and malolactic fermentation, as well in sparkling winemaking the duration of bottle fermentation all have downstream consequences on the sensory properties of the finished wine,” Kate says.

Note those terms “secondary” and “malolactic”, also important factors in the final drink. Malo, for short, refers to the conversion after initial fermentation from sugar to alcohol has occurred, of harsh malic acids, created by a naturally occurring bacteria, into lactic acid, resulting in a softer taste and texture and helping to stabilise wines before bottling.

Kate depends on all these factors as she crafts table wines like pinot gris, chardonnay and pinot noir, and then goes one step further in her production of some of Australia’s finest sparkling wines, the Adelaide Hills sourced Deviation Road Loftia and Beltana.

In the making of bottle fermented sparklings, the time-honoured technique also used in Champagne, a further fermentation is employed after the initial base wines have been finished and blended.

In simple terms, the wine is poured into each of the bottles — the very same ones you eventually buy — with a technical shandy of sugars and more yeast, sealed and then allowed to go through another fermentation, which produces carbon dioxide as a natural byproduct that’s trapped in the sealed bottle and develops into the bubbles we all love so much.

The quality of the base wine, the yeast/sugar mix used, and the time allowed for the bottle fermentation to occur then mature before finishing in a process called disgorgement and final sealing with a cork or crown seal, are all critical in determining the final sensory properties of a sparkling wine.

Once the yeast is finished in the bottle, it breaks down and releases amino acids that create a range of aromatic characters from a process known as autolysis. If you read on a back label that a sparkling wine has spent several years on “lees”, that’s the broken down yeast which can over time enhance flavours and textures.

“There’s a lot of work that goes into getting all that right,” Kate says.

“If I taste one of my sparklings two years down the track and it’s all worked out well, honestly some times I just cry, she says.

BEER

Sugar fermenting to alcohol also happens in beer, it’s just the source and methods that change. Essentially the sugars come from grains like barley, wheat, oats, rice, even corn, which are first germinated or malted to create the fermentable sugars ready for yeasts to feast upon and turn to beer.

Specialty malts determine flavours and the balance with bittering hops.

CIDER

Again it’s the sugar source that determines the final flavours, with different varieties of apples in play. Pears, too, are the core of the product also known as Perry.

SPIRITS

We love our artisan spirits, the scores of gins, whiskies, vodkas and brandies now crafted across the country.

They wouldn’t exist, however, if it wasn’t for a company based in Nuriootpa called Tarac Technologies, which converts the bi-products and residuals from the wine industry like grape marc, the masses of skins and pips left over after the fruit has been crushed, into grape alcohol.

First those fruit leftovers have to undergo their own fermentation, before the Tarac team then begins its distillation process, which results in a range of spirits including matured brandy, neutral spirits, fortifying spirits and an ultra-premium spirit much preferred by our gin artisans and other craft spirit distillers.

They then further work that spirit with their own selection of botanicals and aromatics to arrive at the drinks we love so much.