UniSA makes case for managed retreat from properties at risk of storm surges

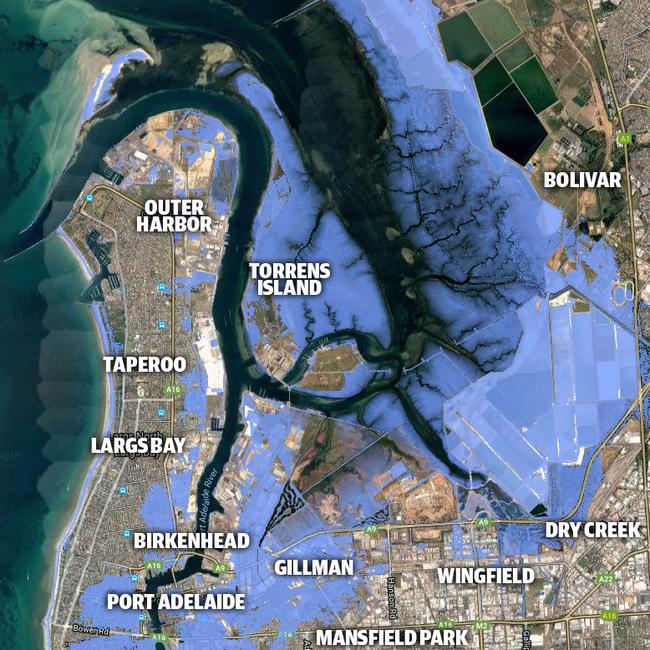

Suburbs around Port Adelaide face stark storm surge risks as sea levels rise over the next century. And SA is missing key equipment to measure what’s happening.

Climate Change

Don't miss out on the headlines from Climate Change. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Extinction Rebellion protesters turn up the heat in Adelaide

- David Penberthy: Science-denying cultists are the real threat

Coastal homes most at risk of flooding might have to be walled off, raised on stilts or evacuated as sea levels rise, UniSA research argues.

UniSA PhD candidate John Watson said options for policy makers included protecting areas by building new structures, improving drainage or a permanent relocation to higher land.

“I found the idea of relocating people from hazard-prone land interesting – it’s inherently controversial,” he said.

“I think it’s a topic that’s under-researched but it’s an important one given the long-term consequences of climate change that governments need to have their head around.”

He cites examples in the wake of Hurricane Sandy in 2012, when residents in flooded parts of New York’s Staten Island asked the US Government to buy their homes.

“There will be communities who will accept the idea of land acquisition because they have been frequently inundated,” Mr Watson said.

“Others will resist because they have a strong attachment to their property and believe the Government’s job is to protect the community and not to intervene in private matters.”

The research investigates whether the idea of relocating people is feasible and, if so, how to do it, when to do it and who should pay. In 2005, Port Adelaide Enfield Council mapped the impact of a once-in-a-century flood.

It estimated the damage bill at $30 million if a major flood hit, rising to more than $70 million by 2050 if nothing was done and sea levels rose by 0.3 metres.

New projections for rising sea levels may mean what is now a one-in-100-year event could happen at least once a year by 2100.

Port Adelaide Enfield Council Mayor Claire Boan said the council was working with state and federal governments, emergency services and researchers to address the risks and identify ways to protect assets and communities.

“Since the 2005 study, we have applied the modelling information to various research projects, including a seawall study to identify coastal-protection options in the Port River and key catchment areas,” she said.

“The (council) has been, and will continue to, invest $11 million per year towards new capital infrastructure to address stormwater management and flooding in low-lying areas.”

Last month, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a special report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate.

Based on current growth in emissions, the projected sea level rise is 0.84m by 2100.

Crucial tidal gauge missing

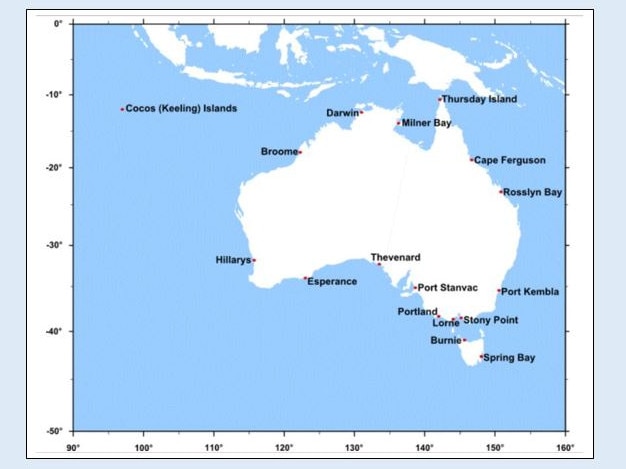

Key equipment to monitor the effect of climate change on South Australia’s coastal waters was removed nearly a decade ago and has yet to be replaced.

The official Bureau of Meteorology tidal gauge at Port Stanvac was taken away in November 2010 when the jetty was closed.

The bureau’s only other SA gauge, at Thevenard, has also been removed temporarily while the port is being upgraded.

Several local councils have written to Infrastructure SA calling for the advisory body to make coastal protection from climate change effects a priority in the State Government’s 20-year strategy.

Onkaparinga Council said the Gulf St Vincent gauge should be restored.

“Accurate long-term measuring of sea levels is essential to understand the actual rise rate,” the council said.

“According to the National Tidal Centre, its (the Port Stanvac gauge) re-establishment is still being investigated in 2019.

“The Bureau of Meteorology has signalled the importance of this monitoring station to our understanding of sea level rise on the southern coastline.

“ … Climate change is exacerbating the impacts of erosion and State Government support is vital for ongoing monitoring and coastal protection infrastructure and works.”

Onkaparinga said the Port Stanvac gauge was in place from 1992 to 2010 and measured an 85mm rise — but data records were now incomplete.

The bureau has a network of 16 stations around the continent, but with none operating in SA, there are no bureau gauges between Portland in Victoria and Esperance in WA.

Instead the bureau is relying on other avenues, including data from Flinders Ports which has its own network of gauges — although they monitor fewer parameters than the bureau equipment.

A bureau spokesman said the organisation was “constantly expanding its broad observations network, including sea level monitoring stations, and works to achieve this by exploring funding partnerships with governments and the private sector”.

It used satellite data and computer modelling to supplement observation from gauges.

“The Bureau is continuing to assess customer requirements and potential funding opportunities for the re-establishment of the Port Stanvac station,” the spokesman said.

Flinders University associate professor in oceanography Jochen Kaempf said assessing climate change was best done by measuring several parameters including water temperature.

“Advanced monitoring stations (together with regular chemical analysis of water samples) would be strategically very important to monitor global warming effects in Adelaide’s marine waters,” he said.

While heat waves and bush fires were of more immediate concern, sea monitoring was important, he said.

Last month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned of accelerating sea-level rise and other impacts on the oceans including heating and acidification.

Onkaparinga was among many councils to call for State Government to fund adaptation infrastructure.

“The large capital cost associated with new stormwater projects to protect communities from flooding and sea level rises is beyond the financial capacity of local government,” Playford Council said.

Alexandrina Council said SA should take a leadership position.

“If not addressed, communities will continue to be vulnerable to the impacts of climate change particularly the Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth and coastal localities as well as industries critical to our economic wellbeing such as agriculture and tourism,” it said.