Mission Zero: What is hydrogen power and how does it work

We’ve known about hydrogen for hundreds of years, but suddenly it’s being touted as the clean, green solution. This is why hydrogen is so hot right now.

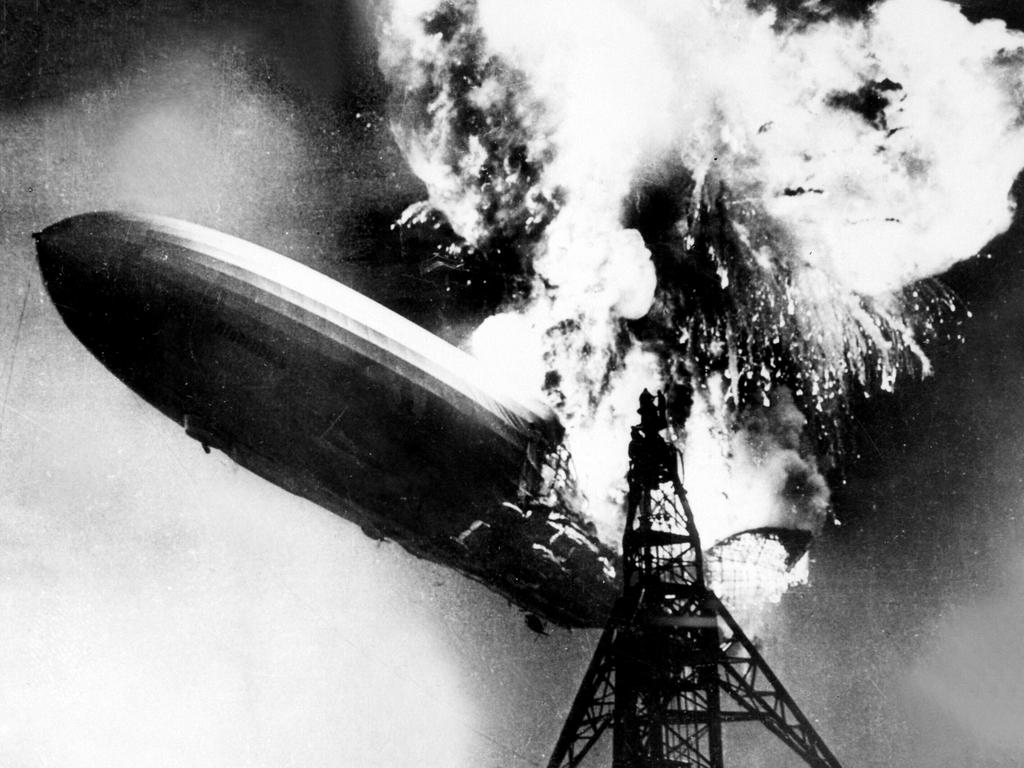

Hydrogen’s reputation went up in flames – literally – when the German airship Hindenburg caught fire as it was docking in New Jersey on May 6, 1937.

The disaster claimed 35 lives and ended the era of the airship. It also stymied the widespread commercial use of hydrogen for decades, although it should be noted the Hindenburg used hydrogen for lift, rather than as an energy source.

Fast forward to 2021, and hydrogen is being touted as the solution to our energy woes. How did that happen, and why?

“It’s really been because of the global move toward decarbonisation,” Hydrogen Council CEO Dr Fiona Simon said.

“It’s time has really arrived because of the need for us as a global economy to move from the existing way that we use energy. Hydrogen has characteristics that we can value more than we could before.”

Australia’s CSIRO has been working on the industrial applications of hydrogen for at least a decade, but its big breakthrough came in 2017, when it developed a metal membrane that enabled the element to be separated from ammonia. This global first was critical because ammonia is much easier to transport than hydrogen.

The next year the CSIRO signed a deal with Fortescue Metals to help commercialise hydrogen technologies. Company chair Andrew ‘Twiggy’ Forrest described hydrogen as “the low emission fuel of the future” and likened the moment to the beginning of an energy revolution.

Developments have come rapidly ever since.

The federal government co-funded one hydrogen export pilot project in its 2020 Budget, and added another four this year.

The CSIRO now lists 74 large-scale, demonstration and pilot projects using hydrogen across the country.

In May this year the organisation launched its Hydrogen Industry Mission, with a goal of driving the cost of production down to under $2 per kilogram.

Former Chief Scientist Alan Finkel calls hydrogen Australia’s “energy hero”.

It seems its potential is just starting to be tapped. Here’s how hydrogen power could change Australia.

WHY ARE WE SUDDENLY TALKING ABOUT HYDROGEN?

Every high school chemistry student learns about hydrogen, the lightest and most abundant element in the universe. It was first identified more than 250 years ago, and we’ve known about its energy-producing properties for a long time. But over the past few years, as the need to decarbonise the planet has become more and more clear, hydrogen has emerged as a possible energy solution as it emits no greenhouse gases. The reason we’ve not relied on it before now? There’s simply been no infrastructure to support it, and financially it’s been unfeasible.

SO WHAT ROLE DOES HYDROGEN PLAY RIGHT NOW?

Currently very limited. Among the few operations up and running, Adelaide-based Australian Gas Networks (AGN) has a pilot project that delivers a small amount of hydrogen (5 per cent) blended into the natural gas supply of 700 homes, with no discernible difference for the user. This hydrogen is termed “green hydrogen” because renewable electricity is used to power the electrolyser at AGN’s Tonsley plant that separates water molecules into their constituent elements, hydrogen and oxygen.

Last year another Australian company, LAVO, started selling a hydrogen battery for domestic use that works with existing solar panels. The battery units are currently not cheap (they retail for $35,000), and somewhat bulky (1200cm x 160cm x 30cm), but they’re safe, and they will extend your supply of solar-powered electricity by three days, even if the sun is not shining.

WHAT ROLE WILL HYDROGEN PLAY IN THE FUTURE?

Massive … possibly. Heavy transport, ships and even aeroplanes could all one day be powered by hydrogen fuel cells, with that latter application bringing the era of “flight shaming” to a welcome end. It could also be used in a range of heavy industries, including cement, glass, aluminium and food production.

“Hydrogen is a possibility for so many different applications across the economy, and we’re still seeing it unfold as to where the greatest uptake would be and by when,” said Dr Fiona Simon, CEO of the Australian Hydrogen Council.

We will see hydrogen increasingly blended in to the natural gas network, she says, with an industry target of 10 per cent by 2030 and 90 to 100 per cent by 2050 – although this will require extensive refurbishment of existing pipelines and the need for different types of appliances.

WHAT COULD IT MEAN FOR AUSTRALIA?

Last year former Chief Scientist Alan Finkel predicted hydrogen could be a $2 trillion global industry by 2050, and Australia had “the potential to be one of the top three exporters of clean hydrogen”.

The government certainly sees the potential, deeming it a “priority technology” under the Technology Investment Roadmap.

This year’s federal budget included $275.5 million for the development of four hydrogen export hubs, bringing the country’s total to five. Another $25 million was allocated to the gas industry to help them make their generators ready for hydrogen.

Announcing a further $68 million for the CSIRO’s Hydrogen Industry Mission in May, Energy Minister Angus Taylor said such an enterprise could employ 8000 people and generate $11 billion a year in GDP by 2050.

Dr Simon says Australia could be exporting hydrogen by 2025, and interest from South Korea, Japan and Germany is already strong. Prime Minister Scott Morrison and German chancellor Angela Merkel signed a “hydrogen accord” at the G7 in June.

CAN’T OTHER COUNTRIES MAKE THEIR OWN HYDROGEN?

They can, and will, but Australia is in a position to create both cheap green hydrogen, because of our abundant access to wind and solar power, as well as the so-called “grey” hydrogen, using natural gas. (While gas is a fossil fuel, and thus produces emissions, it is proposed that grey hydrogen could be made clean if Carbon Capture and Storage technologies live up to their promise. With this added step, grey hydrogen is known as blue hydrogen.)

“We are the logical country in our region to help support countries like South Korea and Japan, who both use an awful lot of energy,” Dr Simon said. “They can create their own hydrogen to a degree, but they can’t create enough. We are very much the logical place for anyone in our region to look to.”

GREEN, GREY, BLUE HYDROGEN … WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

The end product is all the same, but those colours are only the start. There’s pink hydrogen (made from nuclear power), black and brown hydrogen (created using different types of coal) and yellow hydrogen (sourced specifically from solar energy). There is increasing discussion about the need for labelling schemes so consumers understand how their hydrogen is created.

In Australia it seems likely the choice will be between green and blue hydrogen. A recent report by advisory firm EnergyQuest suggested blue hydrogen was cheaper than green and thus had the greatest potential for cutting emissions. Others disagree, including the Climate Council’s Greg Bourne, who recently argued “hydrogen from gas has no place in Australia’s zero emissions energy future“.

HYDROGEN SOUNDS GREAT. WHAT’S THE CATCH?

Cost. Hydrogen will not be competitive until it can be produced at under $2 per kilogram, with the Australian industry hoping to achieve that benchmark by 2030. As the element is highly flammable, and is so small it can even escape through steel, critics say retrofitting existing infrastructure for hydrogen is also likely to be extremely expensive. Others say the water needed to create green hydrogen needs to be of such high purity that will also be a massive cost hurdle.

Hydrogen holds a lot of promise, but it needs the right policy settings to encourage investment, Dr Simon said.

“Hydrogen is competing with an existing industry with existing economies of scale and existing subsidies,” she said. “So much of [hydrogen’s potential] relies on the right policy settings, that we don’t have.”

Some have suggested hydrogen will not live up to the hype, but Dr Simon said it will fulfil its potential: it’s just a question of how much.

“It’s gone past the point where it could fall over. Hydrogen is a thing, it’s real, the question is do we put enough gusto in to make it real, to see it meets its full potential. That’s an open question,” she said.