In 2004, Sally Robbins was written into sporting folklore after inexplicably downing tools on her team at the Athens Olympics. Twenty years on the repercussions of ‘Lay Down Sally’ are still being felt, writes EMMA GREENWOOD and ROBERT CRADDOCK.

It’s the 12-word affirmation that shows Sally Robbins has come to terms with being at the centre of one of Australia’s most infamous Olympic incidents.

“I am at peace with my past and excited for my future.”

Twenty years after Robbins was written into sporting folklore as “Lay Down Sally” when she stopped rowing in the women’s eight final at the Athens Games, it’s a simple post on her Instagram account just over a fortnight ago that gives the greatest hint of how much she continues to be shaped by the events of that day.

Now a holistic health coach and yoga teacher in Perth – she returned to the west coast in recent years after owning a yoga studio in the heart of Brisbane for a decade – the two-time Olympian is working with clients on “self empowerment and health transformation”, having seemingly healed herself.

Robbins was at the centre of a storm of controversy in 2004 after she faltered, then completely stopped, rowing more than 500m from the line in the women’s eight final, causing the Aussies to limp to the finish almost 10 seconds behind their nearest competitor.

The incident quickly became one of the biggest sporting scandals in Australian history

Lay down sally promo 1

Giving up was portrayed as weakness; her inability to push through her physical pain and mental barriers seen as a selfish indulgence that ruined the race for her teammates.

The athlete who was one of the most powerful and technically correct rowers in the boat ended the race prone, lying in the lap of the woman behind her, having contributed nothing to her team’s effort for more than a quarter of the race.

The other members of the crew, dreams of becoming Olympic medallists left in tatters, vented their collective spleens, their raw emotions left to spill over publicly after a failure by team officials to shield them from a baying media.

The tide eventually turned on them as well, the crew called un-Australian for their response to Robbins as they too were thrown to the wolves.

After initially being lampooned, Robbins attracted some passionate defence from rank and file sports fans who claimed she had only done her best, she hadn’t broken any rules, she didn’t select herself and was she really any different from a marathon runner who led early and knocked up?

Some of her supporters defend her to this day and say she has not had an undignified public moment since the race and has resisted significant sums to sell her story.

Rowing’s unwanted legacy

As the current women’s eight finetunes its preparations for the Paris Games rated a genuine chance of a medal, the sport is never far away from that day in 2004 that shaped not only the life of Robbins but every other member of the Athens crew.

Lucy Stephan, a gold medallist in the four in Tokyo, will stroke the eight in Paris in a boat rated a genuine chance of winning Australia’s first Olympic women’s medal in the discipline.

“It really irks me,” Stephan told this masthead of the stigma that still surrounds that race and the sport in general.

It’s been almost 20 years and I’ll walk into an airport (in team uniform) and there’ll be some person that’s like, ‘Oh, Lay Down Sally’.”

“And I’m like, yeah, okay, what about Kim Crow (who as Kim Brennan won the single sculls gold in 2016); what about us in the four?

“We’ve had so many incredible results but in women’s rowing for some reason, we remember the bad thing about it.

“And I think that’s also a part of a part of (what’s driving the current) eight.

“Those girls (from 2004), it’s really unfortunate what happened to them – and I’m sure all nine of them have felt that.”

In the aftermath of the race, Robbins claimed sheer exhaustion caused her to stop rowing.

“Suddenly fatigue sets in and I just can’t move,” she said. “It’s a feeling of paralysis where you just hit the wall.”

The fact was though, that it had happened on several previous occasions, most notably at the world championships in 2002 when as a member of the quad scull that was “blitzing” rivals in the final, Robbins stopped rowing in an action most believe cost Australia the gold.

So well known were Robbins’ issues, her teammates had plans in place.

Vicki Roberts, the women’s rowing team captain who was seated at seven in the boat, directly in front of Robbins, wore a message on the back of her race suit that was meant to take Robbins’ thoughts far away from the mega stresses of the Olympic regatta and back to the soothing vibe of her West Australian origins when no one was watching.

Scribbled in permanent marker between Roberts’ shoulder blades so it would sit right in her crewmate’s eye-line during the race, the message read:

“What’s all the fuss about Sal? It’s just a Canning River race … No big deal!”

Such was the fear that Robbins could falter, coxswain Katie Foulkes even had a Plan B ready to roll out – and eventually had to use it.

Well before Robbins actually stopped rowing, all power had gone from her stroke.

The only person in the boat facing forwards, the cox is both the eyes of the crew and an on-board coach.

Foulkes’ job was to encourage, cajole and nurse, if necessary, her crew over the 2000m journey. She had planned for a “worst-case scenario” of Robbins’ collapsing late in the race but nothing had prepared her for losing her teammate so early.

In former long-serving ABC journalist Peter Wilkins’ book on the race and its aftermath, ‘Don’t Rock the Boat’, released in 2008, Foulkes reveals the moment she had to rely on “Plan B”.

“Sally … we didn’t get her back,” Foulkes told Wilkins.

“So I made the call: ‘We’re down to seven’.”

‘You’re making me sick’

As Australia limped across the line the recriminations started.

Wilkins pulled back the layers of the twisted tale with his forensic book, in which he spoke to a range of crew members who vented their still-tender and often unreconciled inner emotions before its release in 2008.

The broadcaster won a Walkley award that year for his Australian Story on the same topic which carried the clever, compelling title “She’s not there.’’

“The book was the hardest thing I did in my 37 years at the ABC – it was painful to talk to some of them,’’ Wilkins told this masthead.

“It was gruelling at times. There were tears from (some rowers). There was anger, regret, sadness … a whole range of things.

“You could feel the pent-up emotion. Once the crew realised I was serious about doing it, they just let it all out. They didn’t want any stone unturned.’’

That raw emotion in the moments after the race was understandable.

Stroke Kyeema Doyle told Wilkins of the anger of the women after crossing the finish line.

Monique (Heinke) was talking and Jodi (Winter) saying, ‘I’m not an angry person Sally but I’m f***ing angry!’ And Catriona (Oliver) was like, ‘I can’t punch her Julia, you punch her. I can’t reach her!” Doyle said.

Doyle and others were furious with Robbins after she managed to pick up her blade after the race and start rowing, with perfect technique, as the crew brought the boat back to the pontoon.

Julia Wilson, the woman in the five seat directly behind Robbins, in whose lap she had finished the race, was also livid at the sight.

“Julia said ‘Stop rowing Sally, you’re making me sick. If you can’t row in the race, how the hell can you row now?’ Doyle told Wilkins.

“… and I turned around and told her to get out. To just get out of the boat and swim to the pontoon. I told her to hand her accreditation in and walk away.”

The recriminations may have ended there though had things been handled better once the women reached shore.

After Robbins left with the team doctor – another matter with which the athletes took issue given their belief she was not suffering a medical problem – “the rest of us, we just sat at the pontoon and just cried and screamed and cried,” Doyle said.

A team official eventually found Robbins, who had made her way back to the boat park but was crying on her own, unable to face her crewmates.

She was persuaded to answer a few media questions, where she parroted the line encouraged by a media liaison officer that she ‘gave 110 per cent’.

Lay down Sally promo 2

Robbins declined to speak to Wilkins for the book. He said while he felt sympathy for her his final conclusion after his exhaustive research and interviews is that she should not have been chosen in the boat.

“I felt sorry for both sides but the overriding emotion is that despite her great athletic ability Sally probably should not have been selected in the team. It is a team sport.

“There was the infamous quote which came from Julia (Wilson): ‘there were nine in the boat and only eight were operating’.

“In a crew, every cog has to be working. The coach said he would still have selected her for what she gave in the first 1800m of the race but the rowers felt the one thing they didn’t get from Sally was honesty. They felt she should have pulled out.’’

From media spotlight to all but forgotten

Wilson’s comments to journalists set off a fire storm.

Along with an open letter sent to media outlets by Sydney 2000 silver medallist Rachael Taylor outlining Robbins’ history of stopping in races and an interview given to ABC’s Lateline program by Doyle, they dragged the issue into the full view of the public.

As public sympathy and vicious criticism swirled back and forth behind Robbins and her teammates after the race, Wilkins spotted something strange.

One minute they were the most talked about sports crew in the nation … then they disappeared.

“One of the big things I remember was it was almost as if the crew were airbrushed out of history,” he said.

“They would go along to official functions and not be mentioned because they had vented their spleens on the dock in Athens. It was very curious.

“The Australian Olympic Committee’s decision to get behind Sally Robbins and ostracise the crew was a pivotal moment. It was a multi-layered debacle.’’

That move was also a tipping point in the psychological battle for athletes like Wilson.

Without the scaffolding of sports psychologists and with team management failing to immediately debrief the shocked crew, it was always likely the tensions between Robbins and her teammates would become public.

Wilson’s comments to the media had been brief but unambiguous.

“I just want to stress it was not a technical problem out there – no seat broke, there was nothing wrong with the boat, there was nothing wrong with the seven other athletes around me,” she told Olympic broadcaster Channel 7.

We had nine in the boat. There were eight operating.”

When the athletes were reminded by Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) officials of their obligations under team guidelines not to make comments that criticise or disparage the efforts of a teammate, Wilson believed she was facing official censure and could be sent home.

Variously described as “suicidal” and suffering a “major traumatic episode” in the hours and days after the race, Wilson was arguably the most affected in the aftermath, returning to Australia only sporadically for several years after the Games.

The then AOC boss John Coates, himself a former rower who chaired a press conference featuring the eights team in an attempt to put an end to the debacle, believes Australian sport is better prepared to, firstly, avoid a scenario like this today and secondly, have the support systems to better deal with it.

“I think the world has changed since that day,’’ Coates told this masthead.

“There is more attention to the mental side of preparation before an event and certainly there is a much bigger team to handle a crisis like that.

“I am not sure how many people the AOC have but within the sports themselves there is a lot of psychological assistance available to athletes these days. It could have and would be handled differently (today).’’

Emotions soared into the red zone on both sides of the debate and Coates took broadcaster Allan Jones to court and won a $360,000 defamation payout following claims there had been a cover up after the race and team members were “bullied’’ by officialdom.

Allan Jones promo

The lingering questions

So who’s to blame for one of the most controversial events in Australia’s Olympic history? So many questions still remain.

Why did Robbins stop rowing in the final? Why was she selected when it was common knowledge that it had happened before? How were the women left to essentially fend for themselves in the immediate aftermath of the race? Was the crew fair in calling Robbins out so publicly afterwards?

Almost 20 years on, what’s most clear is that the incident has had a lasting effect on all in the boat.

For most of those two decades, few of the members of the 2004 crew have lifted their heads above the parapet publicly.

The most obvious exception was probably the youngest member of the crew, Sarah Outhwaite, who rowed on under her married name of Tait, winning a silver medal in the pair at the London Olympics in 2012 with Kate Hornsey after becoming a mother in 2009.

Tait though tragically died after a battle with cancer in 2016, aged 33.

If time has healed the wounds for the others, it’s hard to tell.

Cox Foulkes, the woman who seemed to hold the crew together to an extent after all hell broke loose in the final, is one of the few rowers with a public profile given her work as an executive coach.

She is still in touch with her teammates, telling this masthead while she was aware media outlets had been reaching out, the 2004 crew’s focus was on the current athletes.

“We are all very much looking forward to supporting our team in Paris and want to ensure they … remain the focus as they represent their country in the Olympic and Paralympic Games,” she said in an email.

Foulkes did comment on the events briefly in 2021 when she appeared on the Idle Australians podcast with James Mathison and Osher Gunsberg.

The black and white presentation of heroes and villains after the race did not sit well with her.

One of the things I really struggled with post Athens was this idea of there being a victim – whether it was us or whether it was Sally – at one point I think fingers were pointed at our coach, and I really struggled with that,” she said.

“You know, so many things we point fingers at someone, when often it’s actually more of a systemic issue.”

Foulkes also revealed how much the fallout from the race had affected her.

“For many years, I really struggled. I tried to work out what I should have done differently,” she said.

“I kept looking at myself. What role did I play in this? What conversations should I have had differently? Who should I have brought in? And I’m sure that like many others, I gave myself a hard time about what should I have done.

“I don’t know what the right answer was because I don’t think there was one – and that was really difficult and still is at times really difficult to get my head around.”

But Foulkes had finally learnt not to be defined by what happened in Athens.

“For many years (decades), I have avoided talking about a moment in life that in some ways I let define me for too long, she said in a social media post promoting the podcast.

“So, as I say to many of my clients, here I am ‘turning towards it’ and trying to shake off some of the load I carry around.”

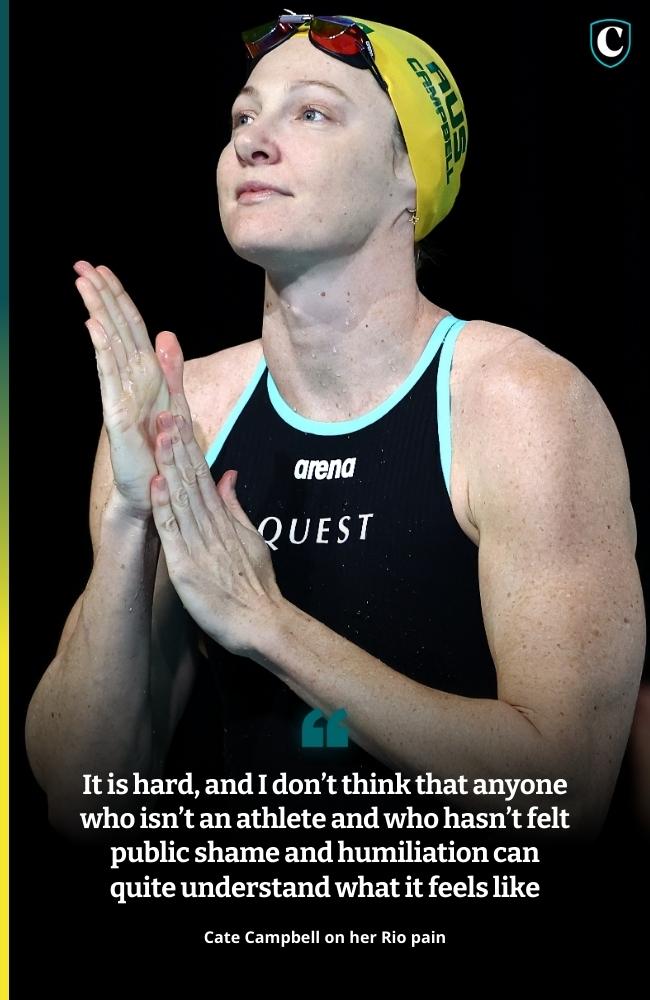

Breaking down ‘public shame and humiliation’

If there’s anyone who knows what it’s like to be in the searing spotlight after Olympic disappointment, it’s Cate Campbell.

The no.1 swimmer in the world in the 100m freestyle heading into the Rio Olympics, Campbell was widely expected to win gold in the event but faded to finish sixth in what she later described as “possibly the greatest choke in Olympic history”.

In terms of understanding the frenzied aftermath that can accompany Olympic disappointment, few are better placed.

“It’s hard and I don’t think that anyone who isn’t an athlete and who hasn’t felt public shame and humiliation can quite understand what it feels like,” Campbell said, drawing a parallel between her circumstances and those of the Athens crew.

“When something like that happens and you feel the sting of shame, your instinct is to recoil, to push back from it, to hide away, to sweep it under the cover.

“But if I turn and look at it and confront it head on, I don’t need to be ashamed of it, because there is so much pride in getting to that place … I didn’t let that one thing define me.”

It may have taken many of them years, but the women from the Athens eight seem to have at least moved on enough to be able to take pride in calling themselves Olympians.

While the entire crew suffered from the events of that day, few outside the rowing community would be able to name a single athlete in the boat outside of the woman who may forever be known as Lay Down Sally.

But the now 42-year-old seems to have taken responsibility for her well being and regained a sense of control over her physical and emotional health – an almost verbatim description of the services she now offers clients.

Just weeks ago, Robbins reposted the AOC’s Olympic Day greeting on her social channels with the tagline “Once an Olympian, always an Olympian”.

“Having this message arrive on my phone every year always brings a tear to my eye,” Robbins wrote.

“I am so proud to be an Olympian and wish our next Olympians at Paris the very best. We are all behind you and know how much hard work you have put in to get to this point.

“I am ever so grateful for the support I received from near and far. (Let’s) get behind our athletes this year.”

Stephan said the eight would be rowing for all crews that came before them in just a few weeks’ time in Paris.

“We’re standing on their shoulders and they’re lifting us up,” Stephan said.

“We learn from our mistakes and we try and make it better.

“I’d love to walk into an airport and have someone say, ‘You’re part of the Paris eight that won gold’, instead of ‘Lay Down Sally’.

“It’s been 20 years and it’s time to move on and it’s about the legacy that we want to bring forward in women’s rowing.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

‘We’re going to deliver’: Premier vows Olympic rowing will be held in Rocky

Premier David Crisafulli has vowed to keep his promise to host Olympic and Paralympic rowing in Rockhampton, despite the outcome of a global assessment on the Fitzroy River.

Albo hints at 2032 Games overhaul, Qld irate

Anthony Albanese has sensationally hinted that several sports may be taken away from Queensland for the Brisbane 2032 Games.