Paul Kent: The murky mix of politics and sport

The politicising of sport has got so bad that nobody knows how to act with any maturity anymore, writes PAUL KENT.

For 48 hours, maybe a little more, Quinton de Kock was the kind of store-bought hero great things can spring from.

De Kock was calling rubbish on the politicising of sport that has got so bad, petrified sporting administrators so much, that nobody knows how to act with any real maturity anymore.

When de Kock did not take a knee in support of Black Lives Matter before the game against Australia this week, he was told he must before the next match. Instead, he pulled out of the game against the West Indies. A day later, under pressure, he apologised and agreed to follow Cricket South Africa’s edict for the rest of the tournament.

Catch all the ICC T20 World Cup action live & exclusive to Fox Cricket, available on Kayo. New to Kayo? Start your free trial today >

Whether de Kock’s turnaround was enough to catapult him into South Africa’s team for Saturday’s game against Sri Lanka remains to be seen.

But while it might be a short-term win for de Kock, and South African cricket, something, somewhere is lost.

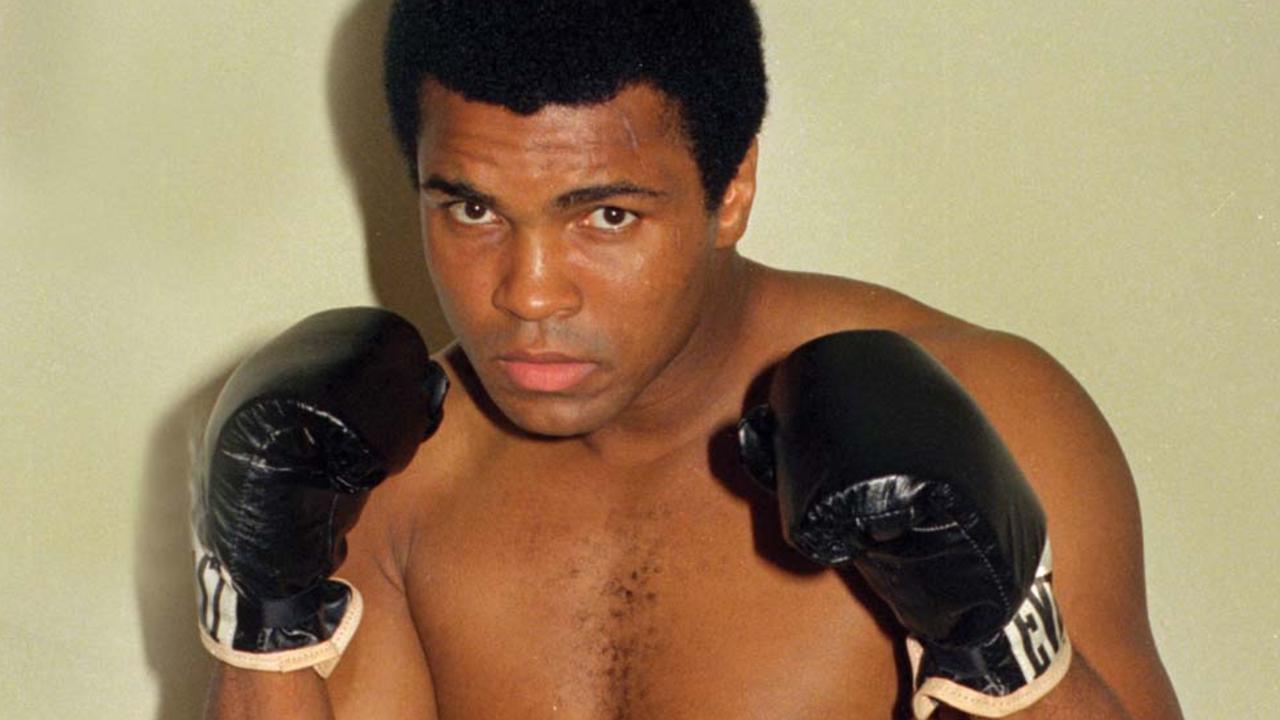

For many of us, it all began with Muhammad Ali, who took a torch to the American civil rights movement when he claimed: “No Vietcong ever called me nigger”.

Ali was some man, surely the greatest athlete of the 20th century, all things considered, but there is a lot of mythology and misunderstanding to his life as well.

Ali was used as a tool by the Nation of Islam. Few realise it was a political party that had no use for Ali or sport in those early years until its leader Elijah Muhammad understood how the fighter could benefit his organisation.

Ali legitimised the NOI struggle and gave it the credibility to be taken seriously, along with a national voice.

When Ali released his autobiography, The Greatest, in 1976, he never actually read it until after it was published.

Instead, it was written by Richard Durham, an editor for the Nation of Islam publication “Muhammad Speaks”.

And more, during the writing each page had to be signed off by Ali’s manager Herbert Muhammad, the son of Elijah, before it was submitted.

“I’m not sure the book is the true story of Ali’s life,” then publisher, James Silberman, later told Ali’s biographer Thomas Hauser.

Regardless, the autobiography was responsible for perpetrating many of the Nation’s political agendas, some even of which went hand in hand with Ali’s own story.

Truth didn’t necessarily matter.

One of the biggest lies of Ali’s life, quoted often in his battle against racism, was that the young Cassius Clay threw his Olympic gold medal into the Ohio River in protest after being refused service at a Louisville diner because he was black.

“Pure balderdash,” Hauser said. “Never happened.”

The lie is still repeated often today, perhaps because it makes the narrative convenient. The medal was, in fact, somehow lost over the years.

The Black Lives Matter message seems to have taken a similar scenic route from the truth.

To the point where a man like Quinton de Kock, who plays and trains and eats and tours with black teammates, whose “half-sisters are coloured and my stepmum is black”, as he said Thursday, withdrew because he did not want to be forced to take a knee in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“For me,” he said Thursday, “black lives have mattered since I was born.”

What else needs to be said?

Sadly it seems a lot.

Quinton de Kock statement 📠pic.twitter.com/Vtje9yUCO6

— Cricket South Africa (@OfficialCSA) October 28, 2021

Like everything in today’s world the struggle is not real until there has been a political stand or an Instagram post supporting it.

When did sporting administrations give themselves the right to assume direction for an individual’s political or social beliefs?

What more must a man do to support racial equality, as de Kock has done, than to live peacefully alongside it?

There is always great danger when politics gets involved in sport, and we should know the warning signs.

Adolf Hitler staged the 1932 Berlin Games to showcase Aryan supremacy but was spectacularly upset by the black American Jesse Owens.

What similar practices are being covertly exercised by the BLM organisation, now calling itself the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation?

Most protesters, for instance, don’t know the difference between the Black Lives Matter movement and the Black Lives Matter organisation.

So whose agenda is Cricket South Africa following? Do they even know there is a difference?

Last August former New York Jets defensive lineman Michel Faulkner, a New York pastor now for more than 30 years, warned of the difference.

“The movement is raw and organic, born of genuine exasperation and frustration and focused on justice,” he wrote in the New York Daily News.

“The organisation is a strident left-wing political agenda wrapped in the language of the newly ‘woke’. It’s critically important that the two forces be separated.”

Faulkner is black, by the way. His ancestors were slaves.

Already many follow the doctrines of the BLM organisation while believing they support the more liberal message of the BLM movement.

“The organisation is now home to political hitchhikers of all stripes who’ve attached to it tangential causes, including transgender rights, radical environmentalism and various social prescriptions,” Faulkner wrote.

“Meanwhile, anarchists — many of them white — are cynically expropriating African-American angst to commit violence and wide-scale theft in our name.”

Not only that, the organisation has become — surprise, surprise — profitable.

The BLM organisation’s co-founder, Patrisse Cullors, bought her fourth home last year in Los Angeles, has two book deals and a movie in the pipeline.

Cullors, also, is a self-confessed “trained Marxist”.

“The first thing, I think, is that we actually do have an ideological frame,” Cullors told The Real News Network’s Jared Ball in 2018.

“Myself and (BLM co-founder) Alicia (Garza) are trained organisers. We are trained Marxists. We are super-versed on, sort of, ideological theories.”

It takes far less than six degrees of separation to trace the BLM back to the Weather Underground, which the FBI labelled a domestic terror group that carried out terrorist acts against the United States Government in the 1970s.

So from which ideology is Cricket South Africa listening to?

So powerful is the external pressure, sporting administrators around the world are being cowered into pushing the organisation’s political agenda onto its athletes for fear of being labelled racist.

And how do they defend those accusations to sponsors?

The sad part, the obvious part which everybody has missed, is that sport in itself is already the most unifying weapon we have.

When maturity was shown, politics was comfortably kept in the background because the athletes, front and centre, invariably overcame it.

De Kock plays with black players. As the keen-eyed have noticed, he tours with them, eats with them, trains with them, celebrates with them … and they with him.

There is no racial line.

How was forcing de Kock to take a politicised stance helping racial inequality?

It was doing the opposite.

Sport fights racial inequality every day by the very act itself, of players heading into battle and competing with each other, and relying on each other, and trusting in each other … needing each other.

Without that, none of them win.

And none of us do, either.

SHORT SHOT

The NRL needs to urgently revisit its Covid protocols before training resumes on November 1.

In the surface, it appears the NRL has once again been strong and proactive and a step ahead of other sporting organisations. Except it does not make sense.

Unvaccinated players are subject to level four protocols.

Essentially, that means the clubs must provide unvaccinated players with a separate area to eat during the week, away from teammates, and they must train separately, do their weights separately and even shower separately.

This means the clubs must find a trainer to wear full protection gear while taking the players through their training sessions, for instance.

But how do the players do ballwork with their teammates?

How does the vaccinated halfback take the ball and toss it to the unvaccinated backrower, with the vaccinated centre outside him?

The true absurdity, though, is that after being isolated from their teammates all week the players are then allowed to come together to play as one on the weekends.

Clubs suspect the NRL is distancing itself from taking the stance other sports have taken to avoid legal action, lobbing it into the club’s laps.

On Thursday it was revealed Melbourne’s Nelson Asofa-Solomona is currently resisting the jab. In Townsville, it is Jason Taumalolo.

They are players vital to their teams success, through the week as well.

The NRL’s edict sounds good in theory but fails miserably in practice.

How a kid that wasn’t desired, found desire was key

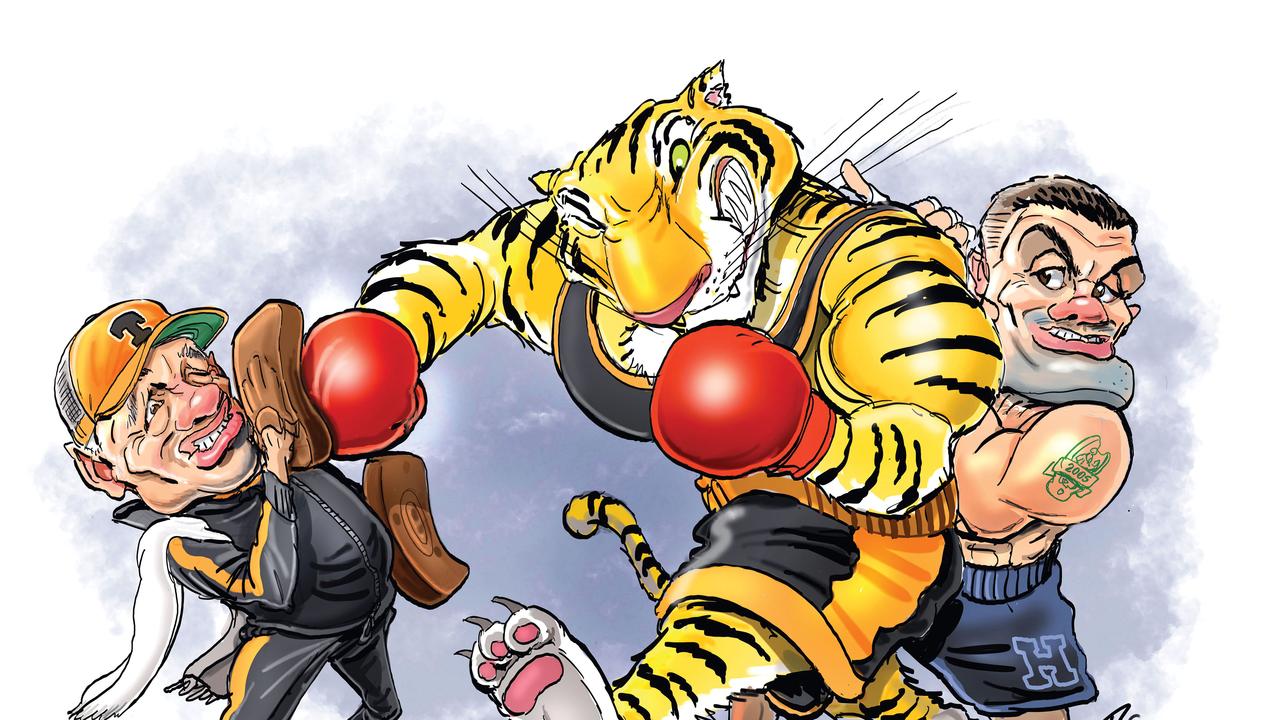

The Chris Heighington story is about as good a place as any to wonder what has become of the Wests Tigers, and what they will become.

It is not a footy story, as such, but a 24-carat tale of a young man who found reward in his effort.

Heighington retired from playing three years ago and now runs his own business getting kids off the lounge and active but, some time next week, he is expected to sign a contract that will bring the Wests Tigers’ past crashing into its present.

The contract will be to fight Tigers’ centre Joey Leilua in Newcastle in December.

The card is being headlined by Paul Gallen, the old warrior and a former teammate of Heighington.

Gallen will fight Manly prop Josh Aloiai in the main event, or at least it is hoped.

The pair are in dispute after Aloiai initially agreed to fighting six three-minute rounds but, after a training setback, has asked for the fight to be switched to four two-minute rounds.

Gallen has gone off, and rightly so.

Every time he fights the rounds seem to advantage his opponent.

It’s the fight before that holds the intrigue, though.

It is like a metaphor for the Tigers themselves.

Earlier this week Leilua shot down a story claiming he was offered a train and trial contract with the Tigers before ending it with a flourish, taking a swipe at coach Michael Maguire.

“Btw, I wouldn’t play for someone that blames the team all the time! And not once himself! #Madge,” he wrote on Instagram.

When Joel Keegan read that, all he could do was look across his gym at Heighington, and at the man he has become, and wonder.

Keegan owns the Complete Boxing gym at West Gosford, where Heighington walked into the moment he decided to fight Leilua and where he has been training him for five days a week since.

He and Heighington went to school together, so he knows his story well.

Character always meant something in Heighington’s world. It was a value that was tangible.

It was measured in how hard you worked and how you treated people and how you responded to setbacks.

And each day when Heighington walks into the gym Keegan sees that character.

He sees it when Heighington gravitates to the kids in the gym that are down in confidence, or struggling with the effort.

He trains beside them, encouraging them, getting them across the line.

Keegan has a good young kid in the gym named Sam Goodman and Heighington watches him constantly, seeing what works and how to execute it.

For the kid that wasn’t desired, Heighington found desire was the key to it all.

Heighington was in and out of first grade in 2003 and 2004 and then early in 2005 he thought he had secured his spot when he was driving to Parramatta Stadium to take on the Eels in the 5.30pm Saturday game.

His phone rang.

“Heighno,” said Sheens, “I don’t know how to tell you this, but you’re playing reserve grade.

“You need to get to Henson Park straight away. You’ll get there for the second half.”

Heighington thinks a lot about that phone call.

“I thought it was a test of character,” he says.

He trusted, and whatever Sheens wanted he gave him, and because of that this young kid desired by no-one went on to play more than 300 games, with two premierships.

“Today,” Heighington says, “a lot of kids would have called their manager after that phone call and told them to get them out of there.

“I had some thoughts but I powered on and the next week I was back in first grade.

“I don’t think I got dropped for another nine or 10 years after that.”

Keegan sees Sheens in Heighington every day in the gym.

“My biggest rap on him is his coachability - he brings no ego to a session,” Keegan says.

“He has done most of his training with one of my young guns Sam Goodman and hangs off every word Sam says and watches everything he does.

“When the sparring has been tough and he has been given a lesson he doesn’t look for other answers.

“He sticks to what I’m asking him to do until it’s better. He has been a great example to my young fighters.”

It is a dedication to the coaching that is missing from the Tigers at the moment.

Sheens is heading back to the club and will find it in nothing like the shape he left it.

The Tigers were a club built on work from their own hands.

When the training facilities began to look a little shabby, the club could not afford a freshen up so Sheens, then the head coach, and his assistant Royce Simmons, gathered a few other footy staff together and spent part of their summer giving it a fresh coat of paint.

Now, the club is in superb financial condition. A new $75 million high performance centre is being built, but it has also lost all its soul.

Maguire has tried to bring hard work to the club and the players are resisting. Not all, but enough to have influence.

Leilua was example number one, and he is now out the door.

How Sheens and Maguire work together as a team will be a storyline next season, in a season where Maguire is coaching for his future with a roster not completely convinced.

Hopefully Sheens can bring them together.

Hopefully, he can make the players realise the value of coaching, like Heighington did.

“He is the type of bloke who has appreciated every coach he has ever had,” Keegan says of Heighington.

“Which is very rare,” he adds.

SHORT SHOT

Ben Simmons seems to have taken a leaf from the NRL Player Managers playbook, in particular the chapter entitled “Kicking Stones”.

Simmons was sent home and stood down by the Philadelphia 76ers management after refusing to take part in a practice drill with his teammates but took it to a new level when he refused to acknowledge staff and even teammates as his standoff with the team continued.

Simmons wants to be traded. The 76ers want to keep him.

Enter the manager …

As rugby league fans can well testify, whenever players want to break a contract to take up a rival offer the player will be quickly told by his manager to walk around training kicking stones, until he is so lifeless the club feels it has no choice but to release him.

Some managers have become experts at negotiating for their players at any point in their contractual period, knowing all they need to do is find a nibble and the player is up for renegotiation, no matter how many years are left on his contract.

As Nathan Brown once said, “It means you can never do a good deal as a club.”

That the league allows it is the concern.

The problem is many players are paid on their potential, which means it’s above their current value, and yet the moment they begin to realise that potential in the latter years of their contract they go looking for an upgrade.

As economics goes, it fails to add up.

It gives all the power to the players, strips it from the clubs, and should be a practice that is banned. Is it any wonder clubs get their salary caps bent out of shape.

More Coverage

Originally published as Paul Kent: The murky mix of politics and sport