For the Bears to hit the heights of premiership contention in 1994 three key moves had to be made and they can all be traced back to the same man.

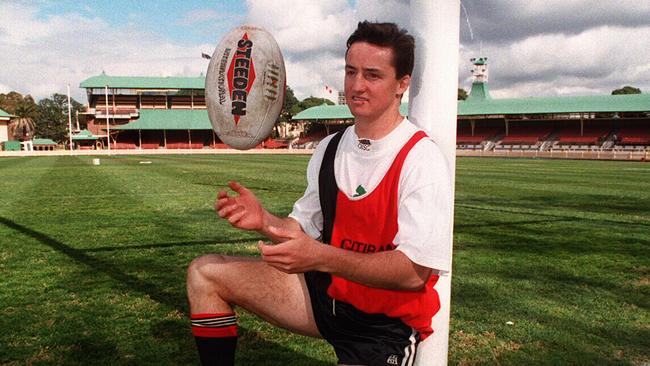

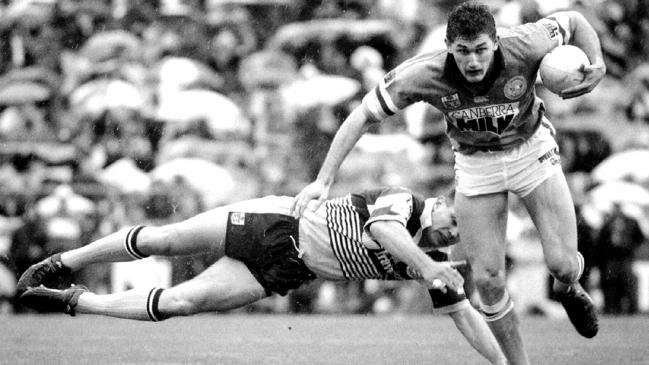

One was easy to spot, even as it was happening – the recruitment of Western Suburbs halfback Jason Taylor.

Halfback had been a problematic spot for the Bears. Jason Martin had claimed the league’s rookie of the year award in 1990 but traded the spot with Mark Soden from 1991 onwards. With Martin’s departure to Newcastle at the end of 1993, the Bears had to land a replacement, and stylistically they needed an on-field general, someone who could steer the team around the park.

Taylor’s excellent kicking game, both in general play and off the tee, were also crucial given Daryl Halligan left for Canterbury.

Taylor made his Origin debut in 1993 and was hot property – Phil Gould had selected him for his interstate debut and tried to lure him to Penrith, but it was Taylor’s link with Bears reserve grade mentor Peter Mulholland, his schoolboy coach at St Gregory’s College in Campbelltown, which proved crucial.

“Peter Mulholland had coached at the Bears, and even though he was leaving and was keen for me to go to the Reds with him he was influential in getting me there,” Taylor said.

“He had a good insight to the club and what they needed, and he thought it would be a good fit. I trusted him, and he was right.

“The biggest thing from a playing perspective was the forward pack the Bears had – I was a skinny little runt, I needed big guys around me, so going to a team with that forward pack was a big part of the decision.”

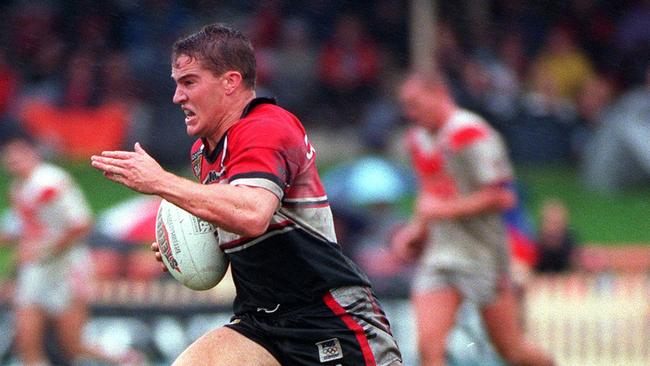

The other new kid on the block was a young fullback from Cudgen, who came to the Bears via St Greg’s as well. There wasn’t much of Matt Seers back then, but he was one of those guys who burnt the ground up behind him as he ran.

The Bears had signed Ivan Cleary from Manly to be their fullback in 1994 but Seers made the job his own and never looked back.

“In the 94 pre-season I was training with reserve grade, but Ivan Cleary got injured before the first game. I got half a trial game against the Gold Coast, and we lost, but two weeks later I played the season opener,” Seers said.

“It was an enjoyable time, making your debut is all you want to do as a junior, all you want is to play in the Winfield Cup.

“Just being there, playing with guys you looked up to, playing against guys you looked up to, it was exciting times, great times.

“The first year is easier, because nobody knows you. None of the coaches know how to stop you.”

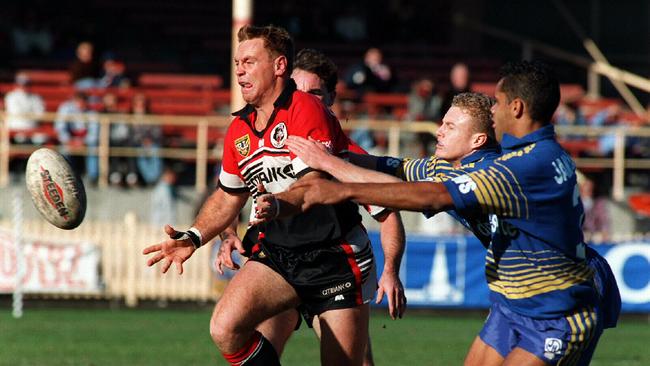

Seers and Taylor were instant hits, giving the Bears the speed and playmaking they’d missed in previous seasons. The new Bears opened the season with seven straight wins, including another victory over the Broncos at Brisbane’s ANZ Stadium.

“Matty Seers, what a find he was, a rough diamond who was polished up to become a glittering star,” Moore said.

“He didn’t know how fast he was.”

Incredibly quick across the ground and able to change direction without dropping gears, Seers was a sensation for the Bears and instantly looked at home at fullback.

His specialty in attack was lurking out wide and attacking the edge of the ruck on the back of offloads, which the Bears were able to throw early and often under Louis.

At season’s end, Seers claimed the rookie of the year award ahead of the likes of Anthony Mundine, Matt Sing, Adam Ritson and that halfback Soden and Jackson had spotted the year before in reserve grade, Andrew Johns.

“Seersy was a bit of a shock for all of us, how well he played,” Taylor said.

“Everyone knew he had talent, but he got a shot early in the season and he made it his own. His performances that year were amazing, he was such a great addition to our team”

While Seers slotted straight in as part of the machine, Taylor’s role was more complex.

He immediately became the Bears’ dominant playmaker, and assumed the captaincy from Rea. Even though he was the new guy, there was no question about who was to take the team around the park.

His combination with Florimo was an instant success, the robust running of the five-eighth pairing so well with his halfback’s ability to distribute and organise.

“With Flo it was a bit different, because he was so experienced,” Taylor said.

“We gelled together well, his running combined with my passing is what made that work.

“That start that we had, it wasn’t too far into the competition when we realised how good we could be. We were confident from early on that we’d be good enough to go all the way.”

Taylor also helped lift the players around him, even established stars like Larson, Moore and Fairleigh.

“He was a great thinker on the game, a leader, and he was essential for that period of our growth, to challenge us as individuals,” Moore said.

“By that point Jarvis and Jacko were gone and Fenech was in his last year, and the new boys changed us from the boring Bears to the high-scoring Bears.”

It wasn’t an easy transition for the club’s other halfback, and after Mark Soden spent much of the 1993 season in reserve grade, his card appeared to be marked.

Mulholland suggested a positional switch that would change the course of his career and give the Bears yet another attacking weapon.

“Peter Mulholland said to me at the end of 93 ‘Sodo, you know they’ve bought Jason Taylor. They’ve paid too much money for him, he’s not going to play reserve grade, why don’t you switch to hooker? You can just run and run, like you would at a scrum base’,” Soden said.

“I was a bit offended, but I went away and thought about it and it had a lot of merit.

“I went in there and played it as I saw it, if there was something on I ran, I started kicking from dummy half, which not a lot of people were doing. For me, it was all new again, it was all fun.

“As a halfback you have to create opportunities, as a hooker you just wait for it to come. To me it was easy, having halfback eyes.”

It wasn’t an entirely easy move for Soden given Tony Rea, the long-time club captain, was packing down at hooker. Rea was a tough and honest performer, very much of the old style of hooker, but Soden’s form couldn’t be denied.

“It was bittersweet. I knew him so well, and we worked together off the field. He’s a great guy, but I knew he wasn’t protecting his position,” Soden said.

“I wanted his spot bad, and I think he saw that. He knew, as a friend, how competitive I was, and I think I caught him on the hop, especially with the running and the kicking.

“He got the team around the field, but I wanted to be more aggressive and assertive.

“The bridges behind me were burnt, there was no going back.”

Rea held his spot in the starting side, with Soden coming off the bench, until Round 11. After their hot start, the Bears had gone four weeks without a win. Louis made the call that Soden would start and Rea would drop out of the side. From there, the Bears won nine in a row and 10 of their final 11 regular season games.

“Mark deserves his chance because he’s been playing good football,” Louis said at the time.

“He sparks up the team when he comes on.

“You can’t keep denying people with better form from playing first grade.”

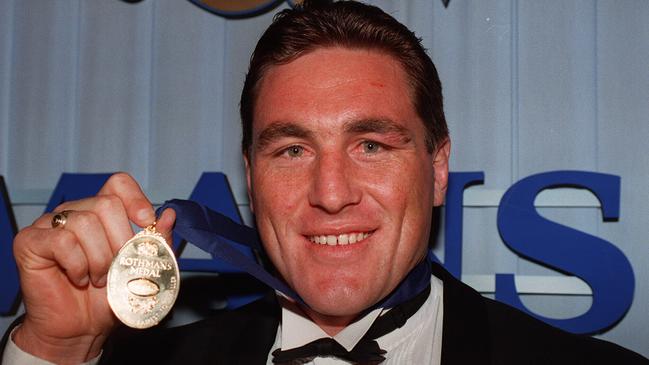

Fairleigh claimed the Rothmans Medal for the competition’s player of the year but Soden got the second-most points of any Bear and only Jim Sedaris polled more among dummy halves, despite Soden only starting for half the year. Rea never played for the Bears again.

A strong personality and confident playmaker in his own right, Soden helped diversify the Bears attack, easing the reliance on Taylor and his structured play.

When the dust settled on the regular season, the Bears were second on the ladder, a point behind minor premiers Canterbury and as deep in the premiership race as a team can be.

Under the old top five system, the Bears would take on Canberra first up, with the winner taking on the Bulldogs for a place in the grand final.

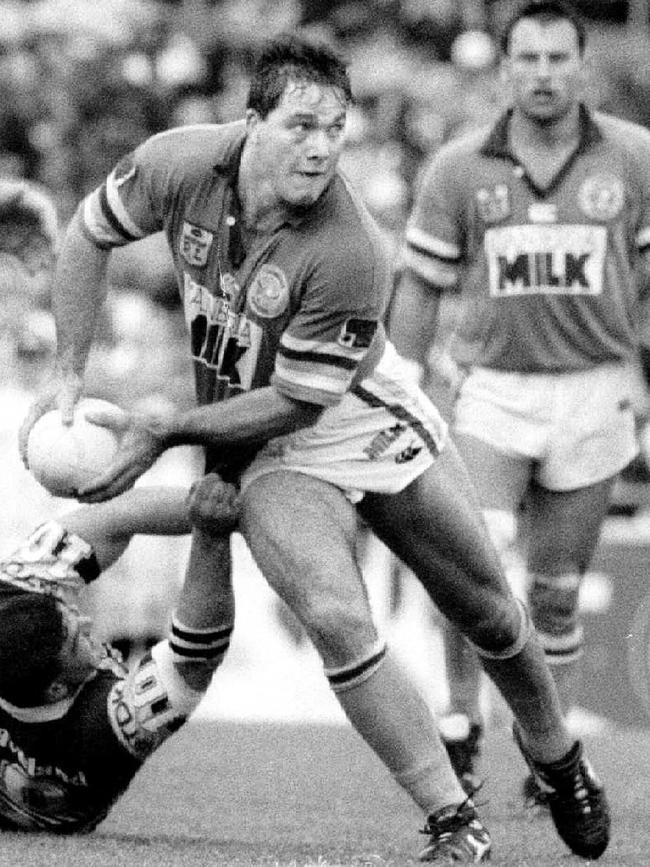

The 1994 Raiders were one of the greatest attacking teams in the history of the sport with creativity and speed all over the park through the likes of Ricky Stuart, Laurie Daley, Mal Meninga, Noa Nadruku and Ken Nagas.

Perhaps their deadliest weapon, and certainly their most spectacular, was fullback Brett Mullins, the fastest gun in the west, who’d torn the competition apart all season. Mullins had scored 11 tries in three games at one point in the year, and the high-stepping, long-striding custodian had fast become one of the sport’s most exhilarating attacking players.

Mullins never again reached the heights of 1994, but it’s important to remember how he was spoken about at the time. Even though it was his first year at fullback such was Mullins’ speed, grace and penchant for the impossible that he was attracting comparisons to players like Graeme Langlands and Reg Gasnier.

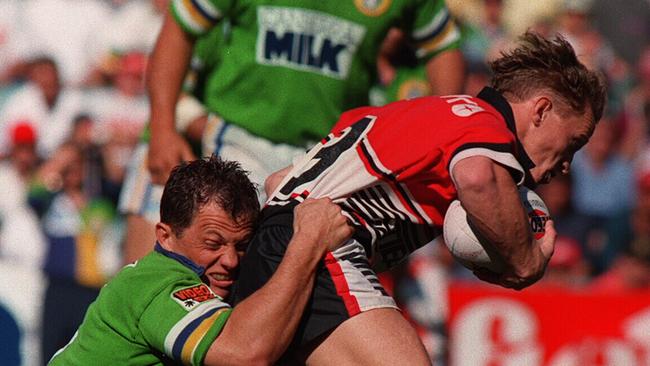

So early on in the showdown with the Bears, when Mullins busted through Soden and Larson on his own 30-metre line and swerved around Seers with nothing but 50 metres of open space in front of him, it was time to put down the glasses. On commentary, Ray Warren decreed they couldn’t possibly catch him.

Seers still isn’t really sure how what happened next actually happened. People still ask him about it today, but he just turned and ran, slowly gaining on Mullins before bringing him down five metres out in one of the great cover tackles in rugby league history.

“It was just exciting. I was lucky – I was pretty quick,” Seers remembers.

“It still gets brought up all the time, but I don’t really remember much.

“I think the commentary made that tackle, Brett was so quick, he was a great player. I just turned and did my best.

“Rabbits is such a great commentator, I think people liked it because Sterlo and Fatty were giving it to him.

“I loved it, all those semi-finals were up at the SFS and it was always packed. We played against so many great teams.”

The Raiders got a penalty soon after, and scored anyway. It was that kind of day for the Bears – Canberra could cut a team in two at the best of times, but Norths gave them more chances than they could ever need, with some bad attacking options handing the Raiders points more than once in a 26-12 defeat.

But it was the sort of match a side learns a lot from, and Seers will always be the man who shot Liberty Valance. Giving Brett Mullins a five-metre start and running him down was ludicrous, impossible, downright against the laws of nature, but Matt Seers did it anyway.

The loss pitched Norths into a sudden-death semi-final with Brisbane, who’d finished fifth and knocked over Manly.

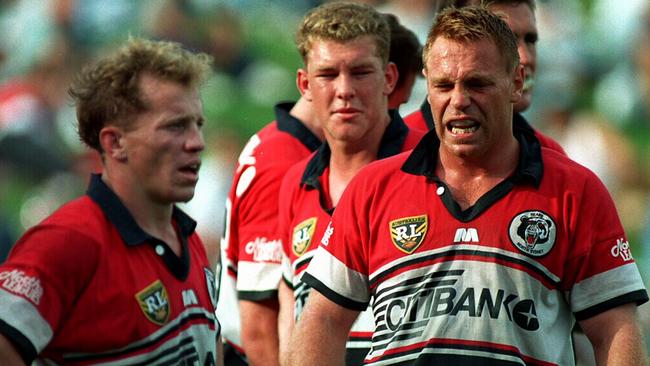

Star power has never been a problem for the Broncos, but they have never been more glittering than they were in the early 90s. You know how everyone talks about the Broncos losing their aura? The 1992 and 1993 grand final wins are where that aura came from, the big bang of Brisbane’s ongoing excellence.

Finishing fifth wasn’t an impediment for the Broncos – after all, hadn’t they won the premiership from the same spot just 12 months before? Brisbane were the semi-final specialists, the big-game players, who grew in confidence and ability as the stakes grew higher.

Between 1990 and 1993 the Broncos had won seven finals matches. Between 1908 and 1993, the Bears had won five. They ‘d only been around for six years, but in the minds of everyone outside of North Sydney, Brisbane existed in another universe.

“The aura of the Broncos then was incredible, and the word aura is right cause they were ‘oh my God’ type stuff,” Soden remembers.

“They were the sort of team who should have won it every year, they were like the Queensland Origin side.”

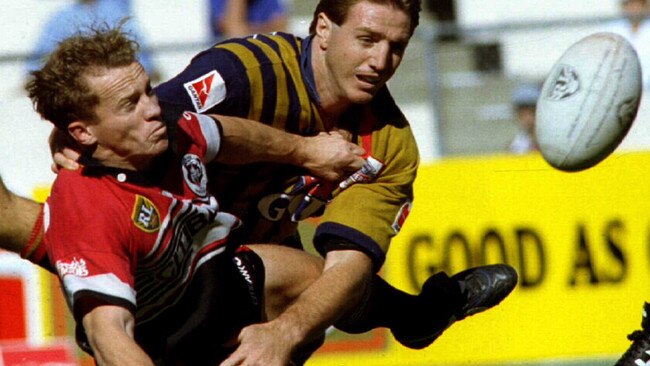

Taylor always relished going against the Broncos, and halfback Allan Langer in particular.

“I always respected his ability, and I used to marvel at the things he did on the field,” Taylor said.

“The other side of Allan Langer and Kevin Walters is that these guys were just out there having fun, it was actually noticeable that they were out there enjoying what they were doing.

“There’d be points in big games where they’d be cracking jokes and stuff. Allan Langer had an amazing attitude in how he played his footy, so different to the majority of people.

“He was just having fun. It was amazing the way he carried himself, and the way he played.”

The sun beat down on the SFS as a crowd of more than 36,000 – most of them pro-Bears – watched while North Sydney took the Broncos aura and beat it into shape.

“I remember the confidence we had to defend our line against one of the greatest attacking teams of all time,” Moore said.

“We knew we were fit and strong, we knew our reads were good, we knew nothing could get past our shoulders.

“That side could do anything. We just had to make sure we delivered.”

Larson played one of his finest matches, scoring a try and setting one up for Greg Florimo, who also had a blinder, while Hall got on the scoresheet off a Taylor cut-out pass.

Fenech also starred – he always gave everything he had, but given he was bound for the South Queensland Crushers at season’s end and this was perhaps his final chance to win a premiership, he found a little bit more. One of the game’s great bleeders, he went to the blood bin four times.

It was 14-all with five minutes to go and the Bears were looking for a field goal when the wholehearted Fenech took the ball up, mistakenly setting up the right-footed Taylor on the wrong side of the field.

But Taylor was a creature born of endless practice, and was prepared for anything. They used to play the Mental As Anything song, Mr Natural, whenever he kicked a goal at North Sydney Oval but Taylor wasn’t that type, not even close.

Taylor was the kind of player who rose well above his natural ability through repetition and willpower. Everything he was, he’d built himself to be.

“I was standing on the left side of the ruck, which is not the place to stand for a right footed kicker, but I practised a lot in the lead up, practised stepping off my left foot and then kicking the goal.

“After Mario got me on the wrong side that’s what I pulled off. One of the Broncos markers came really hard at me, so I was able to get around him and kick it.

“I don’t know if Mario knew that though. He was the toughest player I ever played with, Mario Fenech.”

Taylor banged over the kick from 30 metres out and the Bears held on for a famous win, setting up a rematch with the Raiders for a spot in the grand final, and the win over Brisbane had eliminated any remaining doubts from the North Sydney minds.

“It was real, full-on belief. They were superstars and we just rolled them,” Soden said.

“We kneecapped them and they were gobsmacked – we were too, but for totally different reasons.

“We never thought for one second about how good we were because we didn’t have the egos.”

They packed out the SFS again, because it wasn’t a finals game in the 90s if it wasn’t at rugby league headquarters. This wasn’t like 1991, there were no excuses or torrid clashes to sap the strength the week before. It was straight up, place your bets, and he who blinks first loses.

“I always remember the rooms at the Sydney Football Stadium,” Florimo said.

“They’re just perfect, they felt right. I remember coming out of that room, hearing the noise from the end of the tunnel, coming down the walkway.

“I remember those moments more than moments in the game.

“The atmosphere, the noise, the hum, the significance of the game at the end of the season, the opposition was just another addition to what was already one of the ultimate days of the year.

“I’d look up and see Lazarus in front of me and think it was time to run over Lazarus. It didn’t matter. Langer?

“Let’s watch him, but let’s take him on. We had to take care of our game to not be intimidated.

“The atmosphere and the energy in the joint, you were so focused it didn’t matter who was in front of you.”

Just as Taylor loved facing Langer, Moore relished taking on Raiders lock Bradley Clyde. Acclaimed as perhaps the best player in the game, Clyde was the gold standard for lock forwards.

“Brad Clyde, he was the benchmark. Later on there were other big lock forwards, like Brad Fittler or Jim Dymock. But Clyde was the benchmark always, since we were kids,” Moore said.

“He took the number 13 jersey to a different level. I like to say I was good and Gary Larson was great, with Brad Clyde I was good and he was immortal.

“That was always a good person to judge yourself against.”

If a team got into a quick draw contest with the Raiders they’d always end up losing. That had been Norths’ mistake in their first meeting, they played Canberra’s way and only Canberra can do that.

So the Bears played to their strengths and turned the match into a grind, relying on their forward pack and Taylor’s kicking game to restrict Canberra’s chances.

It paid off when Taylor hoisted a huge bomb, Nadruku knocked it on and Soden was on the spot to open the scoring after just five minutes. It was a North Sydney-type game, as they put the shackles on the Raiders and chained the high-flying attacking machine to the ground. They were made for this kind of football.

Then, after 23 minutes, a godsend. Moore hit it up on his own 30 after Norths survived an attacking raid, and he was smacked round the chops by Raiders hard man John Lomax, who was sent off without delay.

Moore was below his best for the rest of the match, but reducing the Raiders to 12 was worth it. Now the Bears had the room to turn the screws and the Raiders lost one of their enforcers, not to mention one of their best yardage forwards. Without Lomax, the Bears could grind them down and take the skill out of the game. Norths’ path to victory lit up in front of them.

“Lomax got sent off, and Flo said to everyone ‘he’s going to want to even this up. Keep your arms down, keep it safe, don’t do anything stupid’,” Soden said.

“Lo and behold, thoughts become things.”

Barely five minutes later, David Furner hit it up and was enveloped by Tony Hearn and Gary Larson. A renowned hard man with an incredible work rate, Larson was not a dirty player by any means. Lomax always sailed close to the wind – Larson always played it straight.

Except this time he didn’t. Furner got tipped on his head in an ugly spear tackle, and Larson was gone.

“After Tony Hearn and Gary picked Furner up and they were trying to send Gary off, we all said ‘no, no, it was Hearny!’” Soden said.

“Hearny was a good player but we really needed Gary, we all know how good he was.”

Moore was coming to in the sheds and couldn’t believe what he saw once he got his wits about him.

“I remember coming to in the sheds with Gary Larson, and I said ‘what are you doing here, did you get knocked out too?’ and he said he’d been sent off,” Moore said.

“I thought I was having a dream, because how could Gary Larson get sent off?”

A game of 12 on 12 tipped the advantage back to Canberra. Mal Meninga went over to level the scores, and although Taylor snatched the half-time lead with a field goal the Bears were breaking down.

Red-and-black men kept dropping like flies. By the 50-minute mark Norths had lost Gavin Jones, Ivan Cleary and Chris Caruana. Florimo was carrying a busted shoulder after the opening quarter. At one point, the Bears were down to 11 men on the field after running out of replacements before David Hall defied the pain of a shoulder injury to take his place back on the wing.

The Raiders thrived on the open space, but Norths fought on. The final score jumped out to 22-9, as Canberra scored two tries in the final 10 minutes to pull away.

With only one arm working, Hall crossed for a consolation try in the final seconds. The crowd rose as one in tribute to North Sydney’s willingness to fight to the end. Ray Warren called it “a stamp of his character, and a perfect example of what rugby league players are made of” in commentary.

McCallum disallowed it for a forward pass. It was that kind of day.

“It was like a sevens game out there at times. There was so much space and the pace was a cracker. It suited us,” Stuart said after the match.

After the Bears ran out of replacements with 22 minutes remaining, Moore was stranded on the sidelines and admitted after the game he considered running on the field anyway. Hang the rules.

Louis grumbled about some key calls from referee McCallum, especially the decision to send off Larson, but hailed his team’s courage.

“People were out there playing from memory when they mightn’t have otherwise been,” Louis said afterwards.

“There was so much courage. If it was 13 on 13, maybe we could have done it.”

Watching a replay of the Larson tackle there seems to be no doubt it was the right call, but it was controversial at the time.

‘Let’s just say he (McCallum) won’t be invited to my birthday party,” said Fenech at the time.

With a quarter-century of hindsight, Florimo holds no bitterness.

“We can blame the refs or ourselves, and really we can only blame ourselves,” Florimo said.

The Bears lost no admirers in defeat, and traded blows with one of rugby league’s best ever teams. It was scant consolation in defeat, but Norths could be proud of their efforts.

The 1994 finals series is one of the very best ever, with quality matches, epic finishes and truly red-hot sides being the order of the day, and North Sydney played a huge part in it.

“Norths did not deserve this,” Paul Malone wrote in The Courier-Mail.

“To witness their tenacity was to marvel at the heights to which mateship and a shared dream can lift sportsmen.”

Jason Taylor said: “Once it got to 12 on 12 it levelled up, maybe even swung in their favour.

“These teams, the likes of Brisbane and Canberra, they’re some of the best teams ever put together in my opinion, in the players they had and the footy they played.

“But we played against a great team, and a lot of people want to talk about the disappointments but an enormous amount has to fall into place to win a premiership.”

And one day it would have to go North Sydney’s way wouldn’t it? They were young, fit and simultaneously near the top and on the rise. One day it would go their way. It just had to.

It was only a few months later that Super League struck rugby league like a thunderbolt made of money, throwing the thriving sport into a vortex of greed, destruction and uncertainty.

The game’s civil war hit everyone in rugby league hard, and it forced the sport to confront some unpleasant realities that had been festering below the surface for years.

The early 1990s were the boom times for rugby league. The footy was great, the crowds were huge, the beers were flowing and the competition was getting bigger and better all the time. Simply the best wasn’t just a tune, it was an ethos.

It is typical that when the sport seemed to be entering a new golden era, internal forces ripped it all apart. Rugby league’s capacity for self-destruction is only matched by its resilience, but Super League nearly tore it apart beyond repair.

When Super League drew up their battle plans, North Sydney weren’t involved. They had a great side to be sure, but North Sydney Oval and the Figtree and the Percy and the rock-hard cricket pitch had no place in the glittering future.

So the Bears missed out on the initial raids – but once Super League’s blitzkrieg fell short and the arms race began, Norths became hot property.

Accounts differ as to the specifics of Super League’s offers and just what the Bears players knew about the deals and when they knew it, but everyone remembers how the saga took over the entire sport, rendering the games themselves to sideshow status in the mad chase for players, teams and money.

“It was just a shit year, because your focus was never on footy,” Soden remembers.

“It was money, one-upmanship, a lot of people showed their authentic selves when money got thrown around, and that was scary.

“For weeks, that went on. What’s going on over here? Who’s getting what?

“That was a horrible time.”

Many players were unprepared to deal with the situation. They were all professionals, but still had to hold down jobs away from footy to make ends meet. This was from another planet, big business shit, with million-dollar contracts and billion-dollar rights deals on the line.

Clubs became franchises. Footballers became athletes. Cities became markets. Games became content. Television became king and the past became expendable.

“We lost confidence and trust in each other cause we saw the darkness in each other,” Moore said.

“Rugby league people and administrators didn’t trust each other anymore.”

The Super League saga kicked off for Norths after their Round 4 win over Auckland on April 1 of 1995. There had been rumblings

“I remember on the Monday morning we got called in and they told us this revolution was happening – all I could think about was World Series cricket, that it was something like that,” Soden remembers.

“We got called into the boardroom and we got the big spiel off the club. They were ARL aligned – and sometimes they got bullied by Manly, and by Ken Arthurson.

“I think the club thought it was in our best interests.”

For some players, the assurance of the club was enough. Seers had met with Super League the day before.

“I got approached by a manager who wasn’t my manager. I was with Wayne Beavis, it was someone else. We went for a coffee after the game – I was with my cousin, Craig Field, and he told us about Super League.

“We were a bit spun out. They said they wanted to see us the following day. But by that stage Norths and the ARL had got wind of it, and Wayne Beavis said not to go, to see the ARL in the morning instead.

“So I went to the ARL, I was happy with what they offered me and I signed. In hindsight, I should have played one against the other, but I was happy, I was content.

“I was happy at the Bears and I wanted to stay there.”

Soden and utility forward Craig Wilson wanted to get the full picture, so the two organised a meeting with News Limited off their own bat.

“I’m not that great a businessman, but you have to hear both sides of the story before you make a decision. There was thousands and thousands of dollars flying around,” Soden said.

“We got in there, got out of the car, and we didn’t expect anything but the media was everywhere.

“They jumped straight on to Craig, I was crawling along the wall like a Huntsman spider, but then they spotted me, and it was all over the news.

“We had a chat to them and found out what they were offering was not the story we were told.

“Their money was upfront. I’m a player’s player – there were guys at the club like Matt Toshack, who would have to do general duties at the club, or have to go to work after a first-grade game, things like that, to pay their rent.

“I was all about rewarding players who’d earned their stripes.”

Soden and Wilson listened to the Super League pitch, worked out a deal for a healthy base salary and sign-on fee for each player (which each man could then negotiate up if he wasn’t satisfied) and put together a preliminary plan for News Limited to take over 49 per cent of the club, on the condition they’d stay in North Sydney.

“We got everyone to go talk to them (Super League) and even Flo walked out and couldn’t believe the bullshit we’d been told by our own club,” Soden said.

“I pleaded with Flo, because everyone would follow him.

“I said ‘Flo, if we sign with the ARL we’ll be gone in 10 years. This is our chance to get away from Manly. The power base is Fulton, Arthurson and Kerry Packer – Manly people! You think they care about us? They want our vote, they want our number, and they don’t want us. News Limited are throwing everything at us, you name your price Flo! Tell them what the ARL will give you and they’ll probably double it’.

“I was literally on my hands and knees, because if Flo went we’d all go. But we did what we did.”

Florimo trusted the club, and the ARL, as the stewards of the game, and in the end the Bears stuck fast to the establishment.

“Some big decisions were made, and I don’t think they were well-informed decisions in a lot of cases, probably not in my case either,” Florimo said.

“It was trust in the club and the ARL, and that’s what we did. If that was right or wrong, I don’t know – but it was something I was comfortable with.

“These guys were the founders of the game, and they’d done nothing wrong over time, and I had faith they’d continue to be running the game.

“That drove my decision a little bit, but who knows. If we’d spoken to Super League would we be around? I don’t know.”

For some players it wasn’t so much a question of what they could get or what would help the Bears survive, but how they could stick together. The bonds they’d built wouldn’t be so easily broken.

“The biggest thing for me was that we, as a club, decided to stay together,” Taylor said.

“There’s always going to be individuals who were within their rights to do what they wanted to do, but for us as a club, we made a joint decision that we would follow the lead of the club.

“Where we ended up was where we would end up. That means there was more of a collective approach to it, instead of everyone just going out to different directions.

“We made a collective decision, which was really powerful and really strong.”

In the end, almost all of the Bears stuck with the ARL, even Soden, who had a healthy deal on the table from Cronulla.

“I was offered so much more to go to Super League and Wayne Beavis talked me out of it. But I was so comfortable and happy where I was with all the guys.

“I got no advice, I was doing it all by myself. But I’ve always been a loyal person, and I was loyal to my mates and the club.”

Nobody at the Bears could have any idea how precarious their position would become in the years following the war. After all, Norths were flying as high as any team could. They had big money sponsors, good crowds at North Sydney Oval, big-name stars, the works.

It’s easy to say now the Bears should have taken the Super League money, and even easier to get caught up in the possibilities of where the club would be, and how Super League would have changed once they got a foundation club on board.

But these were bizarre times, with clubs rising and falling by the week. Things that seem unthinkable now – like the Roosters merging with the Dragons, or the Tigers relocating to Melbourne, or Brisbane being flat out expelled from the competition – were all seriously explored.

“I suppose nobody knew how it was going to play out, but I wonder how things would have played out if, as a club, we had decided to go to Super League, would that have been a better decision for the longer term future of the Bears,” Taylor said.

“But I don’t have regrets. ‘Maybe’ is an interesting word. There were no guarantees of anything, and at the time we were a really strong team that loved playing together, and we wanted to support the club and have the club’s support.

“In the end, the decision was made and I supported that decision because I was loyal to the ARL. I was comfortable with it, we all were, but nobody knew how it was going to turn out.”

Many of the Bears have noted that when the axe swung and the competition was reduced, none of the clubs who signed with Super League lost their heads.

“We stuck solid to the ARL, because as a playing group we went one in, all in. The administrators at Norths never entertained the thought of us leaving and going to Super League,” Moore said.

“They were more than happy for us to stay on that path. We’re all wiser in hindsight – I wasn’t fully aware how hard Super League chased us, because once I realised we were going with the ARL I had no contact with Super League. I didn’t entertain the thought.

“Retrospectively, we should have paid attention to what was on the table.

“I have no doubt that if Norths had have jumped to Super League, we’d be alive today.

“No existing New South Wales rugby league franchise that went to Super League fell over – there’s some teams today that are lucky to be alive, and the reason they’re alive is cause of News Corp. The ARL were the ones that had to put the knife in.”

The Super League war rippled out in ways that were impossible to imagine at the time and difficult to see even today. As Norths would discover in the years to come, there were no guarantees when it came to the future of footy clubs and cash was on the line.

“I have a shitload of regrets, but I don’t think about them, I just get on with it,” Florimo said.

“It’s live and learn, and try and think of the positives.

“It was still another great period for the Bears.”

The speculation took its toll on Norths. They scraped into the finals in 1995 in eighth spot, a draw against the lowly Gold Coast Seagulls the only thing that got them in.

It was too much, there was too much drama and gossip, too much money, too many contracts, too much uncertainty, to really lock in on football.

Newcastle bumped the Bears off 20-10 in the first week of the finals. The Bears, hit by injury, were without Florimo and Fairleigh and had two players making their first-grade debut.

Reports from the time indicate Taylor, not a player prone to emotional rhetoric, gave an impassioned speech after the game, praising the players for their fighting spirit in the match, and how they stuck together, and declaring they’d be back better than ever before in 1996.

“It would have been around the fact that the season was disrupted, but we’d stuck together, and as a club we’d be stronger for it going forward,” said Taylor, who doesn’t recall the specifics of what he said that night.

“Over the next few years we certainly were.”

Peter Louis noted after the match Norths were probably “one or two players away from being in the top bracket of clubs”. Those players would come, and Norths still had some heady days in their future.

The Super League war raged on, but Norths had made their call and the path was set. Doom was on the horizon though, even though nobody could see it just yet, and over the next few years there were contract battles and courtroom dramas, some guys got rich, some clubs got shot, and God didn’t answer prayers a lot.

Norths couldn’t have known their death was so close. Nobody could have. Super League broke something in rugby league, something that has never fully been put back together, even after all this time.

“The players were professionals, and they were paid to do a job, so it was the fans I felt for and it was the fans who were really robbed. They’re the ones who pay to believe, they pay to buy into a club, into a code and they’re the ones who got shat on,” Moore said.

“The lying, the cheating, the greed, they weren’t the ones partaking in that.

“They had this beloved sport, that they put on a pedestal, the icons they worshipped, they watched them succumb and crumble into darkness.

“They had every right to be filthy, and they have every right to still be filthy. They were the victims, not the players.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout