25 years to the day since Adelaide staged the last Australian Grand Prix on its city streets, Victorian premier Jeff Kennett and SA counterpart Dean Brown detail how and why the coup unfolded.

Jeff Kennett knew the deal was done the moment millionaire businessman Ron Walker lobbed at the doorway of his Parliament House office.

It was some time early in 1993 — perhaps February, Kennett can’t recall exactly when, just that the news Walker carried was big.

So big, it would change the face of Victoria forever. And neighbouring rival South Australia, for that matter — a piece of collateral damage the former Victorian premier still today unapologetically insists was neither his doing nor his concern.

The feat, of course, was Melbourne’s successful bid to sneakily approach Formula 1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone and “borrow” the Australian Grand Prix from Adelaide’s streets.

In an era when “Kick a Vic” was our unofficial state slogan the plot was so devious in the eyes of heartbroken Croweaters that setting up Victoria-border roadblocks and boycotting VB at pubs and bottle-os in retaliation was seriously on the cards.

“I understand how South Australians felt — and I’m continually reminded of it every time I go to South Australia,” Kennett told The Advertiser.

“But my priority and responsibility was to Victoria. That’s the same as Coca-Cola competing against Pepsi, or anyone else. You’re out there to do your best for your company or state, and my focus was very much on rebuilding Victoria at that time.”

Today marks exactly 25 years since Adelaide ended its 11-year tenure as a Formula 1 city with the running of the 1995 Australian Grand Prix on the city’s famed eastern parklands circuit.

The iconic stage was a concrete maze measuring 3.78km long, normally stacked with peak-hour traffic, pedestrian crossings and car parks. Peppered with manhole covers and bumps that sent sparks flying from the underbelly of the race cars, it snaked along Wakefield Road and East Terrace to Hutt Street, through banana bend, Stag Corner and Dequetteville Terrace, before returning to the old racecourse section in Victoria Park.

It delivered unforgettable motorsport moments from downpours and driver revolts to all-time Formula 1 memories including Michael Schumacher’s championship-saving collision with Damon Hill and Nigel Mansell’s 1986 tyre blowout.

And the annual event was a season-ending gala with international glitz and glamour that injected pride to a community still recovering from the double-whammy of a national recession and the State Bank collapse.

And then, it vanished. Suddenly and surprisingly, to all except a select handful who masterminded the heist.

THE PLAN

While South Australia was enduring financial hardship during the early 1990s, Victoria was working through its own difficulty.

Kennett became Victorian premier in October, 1992, and immediately turned to Walker, the late sports management tycoon, to set about turning the image and fortunes of his ailing state.

“At that stage the joke was, ‘what’s the capital of Victoria? Two dollars’,” Kennett said.

“I had asked Ron Walker to look at all possibilities for getting major events here to Melbourne. Ron connected with Bernie Ecclestone, he understood Bernie’s frustrations and annoyance at what he described as the failure of political leadership in Adelaide — and that opened up the door of opportunity.

“Bernie had a very strong personal relationship and commitment to (former premier) John Bannon and had John still been in charge it would’ve stayed in Adelaide. But both (premier) Lynn Arnold and (opposition leader) Dean Brown were worried that signing a contract for the extension of the Grand Prix in Adelaide before the election it might’ve put them at electoral risk.

“That gave us the opportunity to borrow the Grand Prix from Adelaide — so we did not steal it, the Adelaide political leaders at the time, through lack of fortitude and commitment, opened up an opportunity that when we approached Bernie he was only too happy to move given that he’d honoured his commitment to John Bannon, and John Bannon was no longer in office.”

THE SECRET

By about February of 1993, private negotiations between Victoria and Formula 1 head office had advanced far enough that in the void of similar commitment from South Australia, Ecclestone was sold on a move to Melbourne.

Formula 1’s spread to Australia was initially floated by Bannon and as a one-off race to commemorate SA’s 150th birthday in 1986. Ecclestone was so eager to find a Southern Hemisphere street circuit he jumped at the approach, and accelerated the inaugural race to 1985.

In the years that followed, “Adelaide Alive” became beloved by drivers, teams and spectators as a yearly party that delivered South Australia international exposure and economic benefits that were the envy of rival states.

So with that lure Walker, on behalf of Victoria, visited Ecclestone in London and convinced the F1 boss to sign a heads of agreement document, setting in motion the switch from Adelaide to Melbourne.

Kennett remembers the early handshake deal came with a key condition, one that he underestimated the difficulty in honouring — absolute silence.

“I remember Ron came into my office and said ‘Bernie’s agreed, we will have the event. But the condition is we’ve got to shut up about it’,” Kennett said.

“I said ‘that’s fine’.

“But for the next nine months my stomach was in knots. We were sworn to secrecy, so there were only five people in Victoria who knew we’d won it — myself, Ron Walker, the treasurer, the head of treasury and the head of the premier’s department. We were the only ones.

“It was very difficult but we pulled it off and when we announced it here it was a major factor in our rebuilding the confidence levels within Victoria, proving to Victoria that we could be winners again.”

THE BOMBSHELL

Dean Brown won the SA state election to become premier in December, 1993, a month after that year’s Formula 1 season finale in Adelaide.

Speculation had been swirling about South Australia’s place on the Grand Prix calendar, fuelled by persistent road-closure heartburn among city commuters plus Ecclestone’s decision to skip the 1993 Adelaide event.

But nothing could prepare Brown for the shock of learning on just his second day of leading SA that the jewel in the state’s sporting and tourism crown had been quietly stripped away.

“I have a very clear recollection, the day after I was sworn in as premier I had a phone call from Ron Walker, who was chair of Victoria’s major events corporation,” Brown said.

“He said he needed to come to Adelaide to speak to me as a matter of urgency. I told him I had other priorities — I didn’t know what it was about — but he said, ‘I still must come and see you’.

“So the next day he came and showed me a contract signed by Bernie Ecclestone back in September, showing the race had been secured by Victoria.

“To start with, it was a feeling of disbelief. I questioned it — as you would. So I rang Bernie and we had a series of conversations. Eventually, he acknowledged that he had signed a contract that transferred the Grand Prix to Melbourne.”

THE FALLOUT

In the aftermath of the 1991 State Bank collapse that left South Australia’s economy in ruins, sport became a key plank in its financial and emotional recovery.

The Adelaide Grand Prix was the centrepiece of our sporting fixture, while the emergence of the newly formed Adelaide Football Club for the 1991 AFL season signalled an exciting development.

By 1993, the Crows proved they could match it with the big, established clubs in Melbourne by storming to a preliminary final. Football Park was a cauldron for visiting clubs, “Kick a Vic” was our mantra and State of Origin was alive and well in an era that swelled state pride.

“There always had been — but particularly at that time — a strong rivalry between South Australia and Victoria,” Brown said.

“It centred largely on football and when we lost the Grand Prix the immediate reaction from some in the media was ‘well, let’s stop buying Victorian beer’.”

Twenty-five years on, Kennett remains the villain — even if time has eased that perception closer to pantomime status — in the Grand Prix coup.

He insists the sole motivation behind the plot was to fulfil his duty as Victorian premier to improve his state — home to the Grand Prix and MotoGP event, the Australian Open tennis, Melbourne Cup and, excepting this year, the AFL grand final in a sporting line-up that enhances Melbourne’s self-styled claim as the sporting capital of Australia.

“The Grand Prix was a very major contributor to Victoria’s emergence from being a rust-bucket state to, by 1997-98, being a world leader not only in terms of sport but in arts and a whole range of other activities.

“It was a profound moment in starting the rebuild of confidence in Victorians in their own state, and I don’t underestimate the importance of it.”

THE FAREWELL

Brown travelled to London to meet with Ecclestone in the aftermath of the loss, and secured the 1994 and 1995 races before the Australian Grand Prix switched to Melbourne’s Albert Park to open the 1996 Formula 1 season.

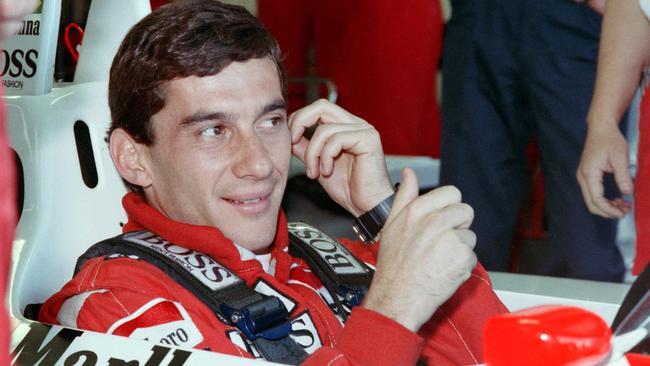

The 1994 chapter came six months after the death of motorsport icon Ayrton Senna in a tragic crash at Imola.

The Adelaide race delivered a thrilling climax to the championship, when Benetton champion Michael Schumacher collided with Williams enemy Damon Hill in a move that ended the race for both drivers but sealed the first of Schumacher’s seven drivers crowns by a single point.

The final goodbye, in 1995, will be remembered for a horror high-speed crash that left Finnish driver Mika Hakkinen fighting for his life.

The race day Sunday also landed in the record books for its crowd of 210,000 — at the time, a world high for a single-day attendance in Formula 1. The mark stood until 2000, when the United States welcomed the category’s return to its shores at the purpose-built Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

But Adelaide’s 1995 farewell remains the best-attended Grand Prix at a temporary street circuit, as well as the largest single-day live crowd for an Australian sporting event.

THE LEGACY

Victoria’s co-ordinated plan to steal the Grand Prix through its major events arm inspired Brown to push for a similar body within South Australia.

“As part of that recovery, after being elected and what had occurred with the Grand Prix, I immediately set up the major events group here in SA,” Brown said.

“One of the events they set up that I then signed the contract for in 1996 was an international bicycle race that became the Tour Down Under.

“And when you look at it now, the economic value and the number of people who view the actual race is far greater for the Tour Down Under than it was even with the Grand Prix.”

Brown backed the decision by current premier Steven Marshall to cancel both the 2021 Tour Down Under and step away from the Adelaide 500, the motorsport event that effectively replaced the Grand Prix.

“With COVID-19 impacting on large sporting events I can understand why it was necessary to cancel both the Tour Down Under and the Adelaide 500 next year,” Brown said.

“Particularly with the Tour Down Under and the now ubiquitous spread of COVID-19 overseas, I can understand fully why it was necessary to cancel both.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

‘Nasty’ Piastri act exposed by F1 champ

Oscar Piastri has been accused of a “nasty” act in a major twist to the McLaren disaster that unfolded at the Canadian Grand Prix.

F1 expert’s brutal title warning after embarrassing Norris blunder

Lando Norris has been warned his F1 title hopes will go up in smoke if he goes down the same path that led to his dramatic run-in with McLaren teammate Oscar Piastri.