Inside story: How to walk the long path to pay equality in sport

The argument that men’s sports are better because the crowds are bigger, the scores are higher and the action is more exciting is a worn out take and totally unfair.

Sport

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sport. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“EQUAL PAY, EQUAL PAY, EQUAL PAY” – that’s what 59,000 spectators chanted after the US Women’s National Soccer Team won the 2019 FIFA Women’s World Cup.

Today, the four-time world champions are still fighting to be paid the same as their male counterparts, who didn’t even qualify for the 2018 FIFA World Cup.

“The Women’s National Team has won four World Cup championships and four Olympic gold medals on behalf of our country. We have filled stadiums, broken viewing records and sold out jerseys,” US captain Megan Rapinoe said in her address to the White House for Equal Pay Day last week.

“Yet despite all of this, we are still paid less than men, for each trophy, each win, each tie, each time we play.

“With the lack of proper investment, we don’t know the real potential of women’s sports.”

Watch every match of the 2021 NAB AFLW Competition LIVE on Kayo. New to Kayo? Try 14-Days Free Now >>

Although some sports in Australia are doing significantly better than other when if comes to gender parity, the gap remains significant.

Australian Bureau of Statistics from 2019 reveal the median full-time annual income for male athletes from all levels that earn money from their sport is $67,652 while women in this category earn $42,900. That is a gap of $24,752.

Female athletes aren’t just fighting equal pay for equal effort – they want equal playing opportunities, access to facilities and equipment, coaches and support.

Weeks ago, Stanford’s performance coach Ali Kershner called out the National Collegiate Athletic Association for providing women’s basketball teams with one rack of light dumbbells and a couple of yoga mats, while men’s teams were given a plethora of gym equipment and space to train.

Despite the disparities at play, women’s sport is increasingly proving that it can be in fact, an exciting, valuable and lucrative product.

Why else would broadcast giants BBC and Sky Sports sign a three-year worth broadcast deal – worth £7-8 million ($12-14 million AUD) per season – to show the FA Women’s Super league?

Ronda Rousey was one of the UFC’s highest-paid fighters because she brings viewers and money to the sport.

Still, knuckleheads at the local pub persist with the argument that men’s sports are better because the crowds are bigger, the scores are higher and the action is more exciting.

University of NSW Professor of Practice in Economics Tim Harcourt said this logic is unfair and unproductive.

“Grow sports together, don’t get in a gender war about it,” Harcourt said.

“It’s important to invest in all sports, men’s and women’s. You get a healthier population, people work better, people have more time for their families, it creates economic improvement in terms of a happier and healthier workforce.

“(Women’s sport) has been quite successful, so there’s a bit of momentum to build on. There has been a huge burst, because it was neglected for a long time.

“If you look at AFLW, they had huge crowds the first few games they had … but you can’t expect that to go at the same level (as AFL) because they have to catch up.”

Harcourt also said that upfront investment, including player remuneration, is vital to developing saleable competitions.

“Cricket used to be amateur, they were semi-professional … once Kerry Packer brought in World Series Cricket, players got better pay and share of the revenue,” Harcourt said.

“Women almost need a Packer-type evolution, to get a better share of revenue. I think that will come.”

Harcourt praised the AFL’s decision to allow free entry while the AFLW established itself as a competition.

“It allowed enough people who were curious to go along and it got good crowds. While you’re not paying anything, you still had to get the train or bus in,” Harcourt said.

“Now they can start charging, which is better for the players because they can get paid, and you’ve got more revenue.

“It was smart to make it free initially, but then you have to put a price on it. You get people interested, then allow them to put a value on it, by paying. And they are paying.”

The economist also suggested cross subsidising AFL and AFLW memberships and believes that male athletes should actively support their female counterparts.

“They shouldn’t be seen as competing against each other … for example, the Hockeyroos and Kookaburras always really support each other,” Harcourt said.

“If the Opals represent Australia at the Olympics, they’re not representing Australian women, they’re representing Australia. Men want to see the Opals win, or the Hockeyroos, or the Matildas.”

Today, Cricket Australia (CA) is reaping the rewards of investing in its female women’s program.

In 2017 CA and the Australian Cricketers Association reached a landmark pay deal that saw its female player payments increase from $7 million to $55 million.

The average female cricketer on a CA and WBBL contract earned $193,000 across 2020-2021.

CA also launched a parental leave policy to support its professional cricketers’ though pregnancy, adoption, return to play and parental responsibilities.

It’s a different story for domestic players.

The average female cricketer on a WNCL and WBBL contract made $49,747 – plus WNCL match fees and prize money – across 2020/21.

Many of these domestic players still rely on second jobs and other forms of income.

Australia wicketkeeper Alyssa Healy has been vocal about increasing pay for state players - to ensure the succession and continued dominance for the international team.

Still, overall, the evolution has been remarkable.

It can be traced back to 2001 when former Australian captain Belinda Clark led the integration of Women’s Cricket Australia and the Australian Cricket Board (now CA).

“If your agenda is to grow and provide more girls an opportunity to play, you need to leverage the system that’s in place to do that. Otherwise you spend time building a parallel system which will always be smaller and less resourced,” Clark said.

“All of the progress, really, you can pinpoint it to that point in time, where the organisations came together and opened the game up.”

Clark called for all sports to reconsider how they allocate funds for both female and male athletes.

“Sports need to think about where they are investing the money they’ve got. If you’ve got money, you’re making choices about where you’re spending it, then you’ve got an opportunity to change the course of history,” Clark said.

“If you have a sport that doesn’t have a lot of money, I would argue that you should think about how you look after those athletes equally, whether they’re male or female.”

HOW VENUS FOUGHT FOR FAIRNESS

— Liz Walsh

When tennis star Venus Williams won Wimbledon in 2000, it was the fulfilment of a childhood dream.

But after all Williams’ hard work to make it to the professional tennis circuit, she realised something she’d not known before: that the male champion received more prize money than she did.

Some 20 years ago, the male champion won £477,500.

The women’s singles champion earned £430,000.

“From then on, I felt compelled to campaign for equality for women,” Williams wrote last week in a column for Vogue.

For Williams’, it’s been a two-decade long fight for women’s pay parity both on and off the tennis court that continues to this day.

“It wasn’t until 2007 when I became a four-time Wimbledon champion that I received equal prize money to my male counterparts – the first woman to do so,” she wrote.

“The road was long and meandering, and it took 39 years of women fighting for equal prize money; more than two years campaigning with the WTA, and an opinion piece in The Times to get there. But now we have equal pay in tennis at the majors and combined events – true equality.”

Women’s sport is filled with athletes just like Venus Williams.

Those who stand up and say: This inequality is not OK. Things need to change.

Among them is Norway’s star striker Ada Hegerberg, who in 2019 became the first woman to win the Ballon d’Or as the world’s greatest female footballer – and was then famously asked where she could “twerk”.

Hegerberg has refused to play for her country’s soccer team since 2017 – even boycotting the 2019 FIFA Women’s World Cup – over entrenched inequality between the men’s and women’s teams.

Sometimes it’s entire teams that stand up to the inequalities in sport: in 2015 the Matildas became Australia’s most successful soccer team when they qualified for the quarterfinals of the World Cup.

Back in 2015, a basic Matildas contract was $21,000/year, while a Socceroo will have earned more than $200,000 (despite the women’s side then being ranked ninth and the men 58th).

The team went on strike, even withdrawing from a tour of the United States.

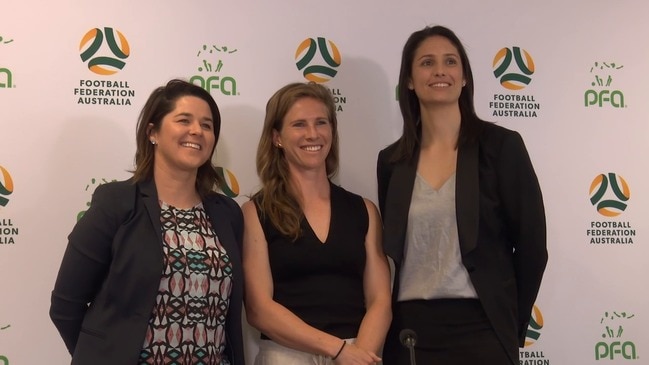

In 2019 the Football Federation Australia announced a new pay deal that increased their annual salary by more than $30,000 to $100,000 and provided the same access to off-field benefits including business-class flights, training facilities and specialist performance support staff as the Socceroos.

It was reported that Socceroos captain Mark Milligan was key in the push for an equal pay deal.

Over the US, in 2019 the US women’s soccer team filed a gender-discrimination lawsuit against the US Soccer Federation. Their fight continues.

In pro-surfing, there has been a concerted push to rid the sport of pay inequality thanks to a number of high-profile women’s surfers, including former champion Layne Beachley, as well as organisations like the Committee for Equity in Women’s Surfing, shining a light on the issue.

In 2019 the World Surf League required that prize money be uniform for both women and men.

More Coverage

Originally published as Inside story: How to walk the long path to pay equality in sport