The Socceroos’ golden generation lives on, as their sons and daughters take the torch

THEY’RE the sons and daughters of Australian soccer’s golden generation — and they’re ready to carry the torch into a new era for the sport.

World Cup

Don't miss out on the headlines from World Cup. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE great outdoors, waves of European migration and a trailblazing national league all sensationally blended to produce the Socceroos’ golden generation.

Some were supported or cajoled by parents, uncles or grandparents. Others were driven to surpass older siblings. All products of their environments.

Times have changed but sons, and daughters of the golden generation are emerging and writing their own stories — home and abroad.

BERT: We can handle the heat

VAR DISGRACE: ‘It’s going to ruin football’

Some have shown enough promise to be in “the system”, training with professional clubs as the first steps to potentially literally following in their dads’ footsteps.

Julian Schwarzer, 18 is at Fulham academy though looking to drop down a few divisions to gain first-team experience, Tony Popovic’s eldest sons Kristian, 16, and Gabriel, 14, are Western Sydney Wanderers youth players along with Oliver Kalac — the son of Zeljko.

Josip Skoko, Paul Okon, Mile Sterjovski and Jason Culina are among those who have kids playing in the National Premier Leagues while the young sons of Brett Emerton, Vince Grella and Olyroo turned Croatia international Joey Didulica have just started while Tim Cahill’s kids are now playing in the US.

To a man, the dads — who’ve been exposed to brutal realities and arduous road to the top, which gets overshadowed by the glitz and glamour — do not pressure their sons. In fact, it’s the stark contrast.

LAST CHANCE: Socceroos reputations on the line

DEADLOCK: FIFA’s emergency plan for historic Group C gridlock

TIMMY TIME: Cahill’s response to selection drama noise

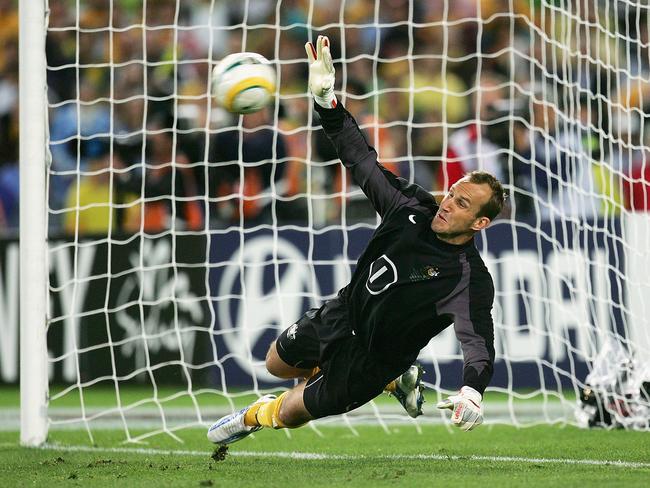

Socceroos legend Schwarzer offered a realistic assessment to son Julian, an outfield player at the Fulham academy, when he dropped the bombshell.

“He was an outfield player and just decided at one stage, ‘dad I’ve always had this thing in mind about going in goals’,” Schwarzer says.

“I said ‘are you serious? You really want to do that? You’ve had the comparisons because of me outfield, imagine what it’ll be like in goals?’

“I’ve always said don’t play football for me, play it because you want to. I’ll love you no matter what.

“It’s the best thing in the world if you play, make a career out of it. If you don’t there are other things you can do in life.

“Now he needs genetics to kick in. He’s 178 centimetres, needs another six centimetres, which you can do up until 21. Then he’s got he’s got half a chance. He’s fighting an uphill battle now.”

SONS OF A GUN, AND A COACH

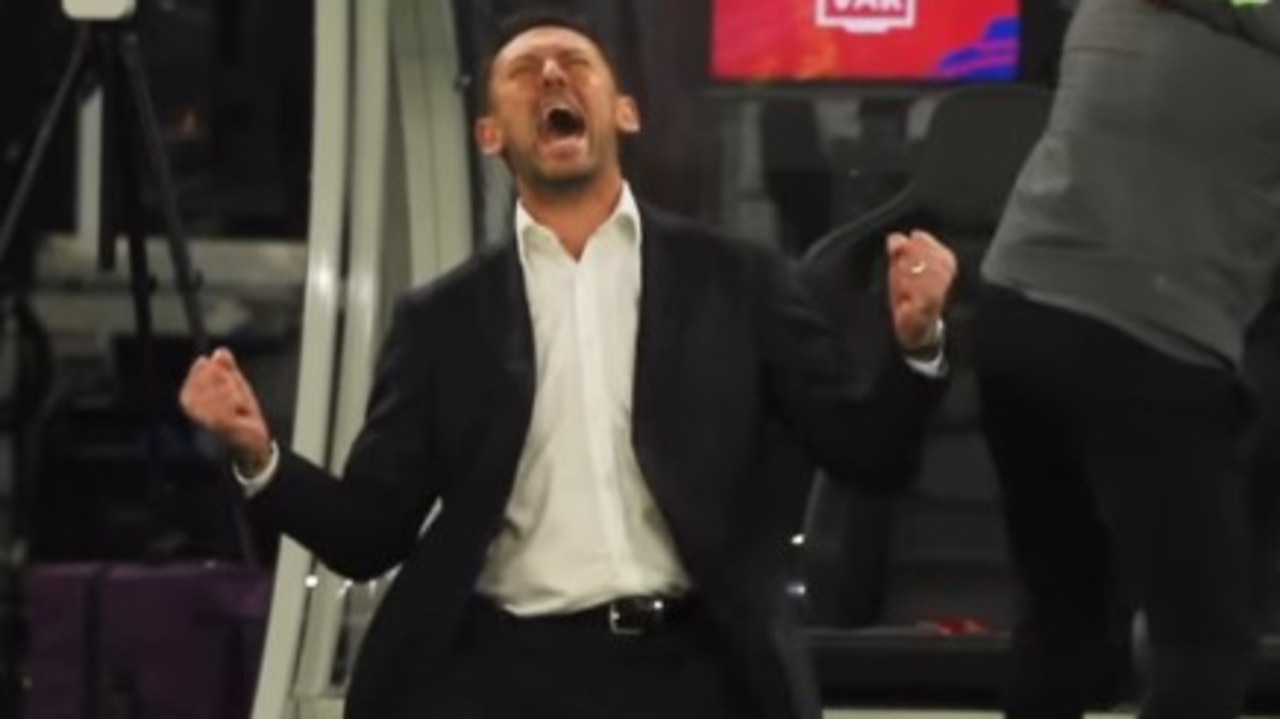

The elder Popovic son was handed debut in a pre-season friendly nine months ago, when Tony Popovic was still coach.

“It’s a unique situation. When Kristian had his debut in a friendly against Melbourne City, it was very interesting,’’ Popovic says.

“Bringing him on, as a father there was so much pride, hoping he does well. Then, you’re trying to keep your coach’s hat on.

“You can’t prepare for that. But I was proud because I know the boy deserves it. I look forward to seeing them both develop and evolve.

“It’s never been an issue. They’re strong minded, down to earth and clearly at the Wanderers because of their own talent.

“They understand the situation, they feel no pressure from me. I’m there for support as a father. That’s the number one priority.”

EURO CULTURE

Josip Skoko’s sons Luka and Noa’s obsession stems from their days in Europe, as they jumped on the Manchester United bandwagon dad was at Wigan Athletic.

Then they were exposed to the fanatical Hajduk Split fans in Croatia when Skoko returned to his first European club.

“By the time we moved to Australia (2010) they were hooked,’’ Skoko says.

“I didn’t push them. From young they just had fun with it. I wouldn’t be disappointed if they pursued it, nor if they didn’t.

“When you’ve had it for so much of your life, you know the good and bad. So if they want it, they can go out and get it, let them earn it. I’ll help them along the way. I’m certainly not going to push them.

“They have to push me for me to help them. I don’t go out and say it’s time to (train).”

OTHER PURSUITS

Harry Kewell often fills in for teenage son Taylor’s five-a-side team in England and hasn’t lost his competitive edge, reminding the Herald-Sun that he scored in last week’s 2-2 draw.

Taylor Kewell had talent but opted not to pursue it, and is keener to follow his mum Sheree Murphy’s creative footsteps.

Europe-based Mark Viduka’s three boys have all played at some stage, but the two older ones did not embrace it like their extraordinarily talented dad did.

Craig Moore’s son Dylan still plays socially for Runaway Bay, but works in sales and marketing.

DON’T FORGET THE GIRLS

Sterjovski coaches his three kids — Blacktown Spartans juniors Luka, 13, and Sonny, 10, and daughter Lilly, 6 — via his MSFC Academy.

“It’s a reason I started the academy — a good way of supporting them, keeping them active and interested in football,’’ Sterjovski says.

“It’s competitive in the backyard, often ends in tears, but we try keep it light hearted. Sonny and Lilly like to follow in Luka’s footsteps but they all love it.

“I don’t want to put that expectation on them that they have to be pros. I told them I’ll be super proud of them regardless of what level they’ll get to and wherever they are I’ll be there supporting them.”

Teen Kyah Cahill has shown tremendous flair in performing arts but he’s still playing in New Jersey while younger brother Shae, 13, is training with New York Red Bulls’ academy. Daughter Sienna and youngest son Cruz, 5, also plays.

“We’re back in New Jersey and the kids are playing there. In America it’s everywhere,’’ Cahill said.

“When I was back just before joining Socceroos camp, we were at three different training sessions and they train five days a week. It’s constant.”

Some will make it, others will pursue different paths. Either way, the golden generation’s fatherly love is unconditional.

Originally published as The Socceroos’ golden generation lives on, as their sons and daughters take the torch