Nearly one in five elite Australian junior cricketers are of South Asian heritage. That number is closer to one in 25 at the professional level. Why is the gap so big? Jacob Kuriype investigates.

Thirteen years ago, Usman Khawaja made his Test debut at the SCG and it was meant to be a sign of things to come.

The first step towards Australia’s men’s cricket team representing a grassroots playing base as multicultural as any in the country.

Fast forward to today, and Khawaja remains the one player of South Asian descent regularly playing cricket for Australia’s men’s team, and at 37 he’s much closer to the end than he is the beginning.

There are green shoots of course.

Tanveer Sangha and Ashton Agar have both been involved in the national white ball sides for extended periods, while all six men’s state sides have featured a South Asian heritage (SAH) player in either a List A or first-class match this season.

Significantly, Alana King has established herself as one of the stars of the women’s national team. Further to that, this year saw three Indian origin players in the Australian Under-19s women’s team.

Still, with the SAH diaspora growing at a rapid rate in Australia, and even quicker within the cricket playing community, Cricket Australia (CA) and its state associations know there are issues that need resolving, and an opportunity they cannot miss. And a mountain of work is being put in.

THE BIG DROP AND WHY IT MATTERS

At the grassroots level, South Asian participation rates are booming. Those numbers flow through into the national pathway system. It’s through the final years of the pathway and during the transition into the professional system that a schism appears.

In 2022/23, a healthy 18 per cent of Australian pathway players were of South Asian background. Despite that, SAH cricketers make up only four per cent of first-class players in Australia.

There is clear growth at the pathway level. In 2013, 11 per cent of the Under 12s players in the national team pathways system were of South Asian descent, and five per cent of Under 17s and Under 19s. By 2023, those numbers had shot up to 40, 16 and 10. They’ve only gone up since.

On the girls’ side of the ledger, the boom has been even greater, going from 2, 5 and 6 per cent for under 12, 16s and 19s in the national team pathways program to 25, 18, and 10.

The question cricketing bodies are intent on working out is why there is a drop off across the senior age groups, and why even fewer make it through to the first-class system.

As former Australia Under-19 captain, and current South Australia player, Jason Sangha puts it:

The numbers don’t really add up.”

It’s a problem Cricket NSW (CNSW) are wrangling with as part of their South Asian Engagement Strategy, and one chief of cricket performance Greg Mail says is important beyond mere representation.

“Across the passage of time it’ll be crucial from a performance perspective that an enormous part of the population is nurtured and harnessed in the right way,” he says.

It’s a problem in two parts for CA, who identified it as a priority to address within its Multicultural Action Plan last December.

“One, it takes time,” says James Allsopp, CA’s chief of cricket. “We’ve obviously had strong migration growth and these kids and talented players are certainly coming through. We want to make sure they’re nurtured in terms of progressing into elite contracts.

“But, two, we don’t know if there’s any barriers yet either.

“One part of the action plan we’re committed to this season is just understanding what is the experience of a cricketer of South Asian background in the pathway system?

“We’ve got some hypotheses, like does education become a real challenge when they’re sort of 16-18 and they’re finalising their exams? Is that a higher priority than someone who has a non-South Asian background?

“We sense that that might be the case and how they juggle those things might be a challenge. But the truth is we need to know more.”

He says this year CA will be regularly speaking with SAH players throughout its 17s and 19s programs as a fact finding mission.

As to the education theory, he could be onto something.

DIFFERENT PRIORITIES

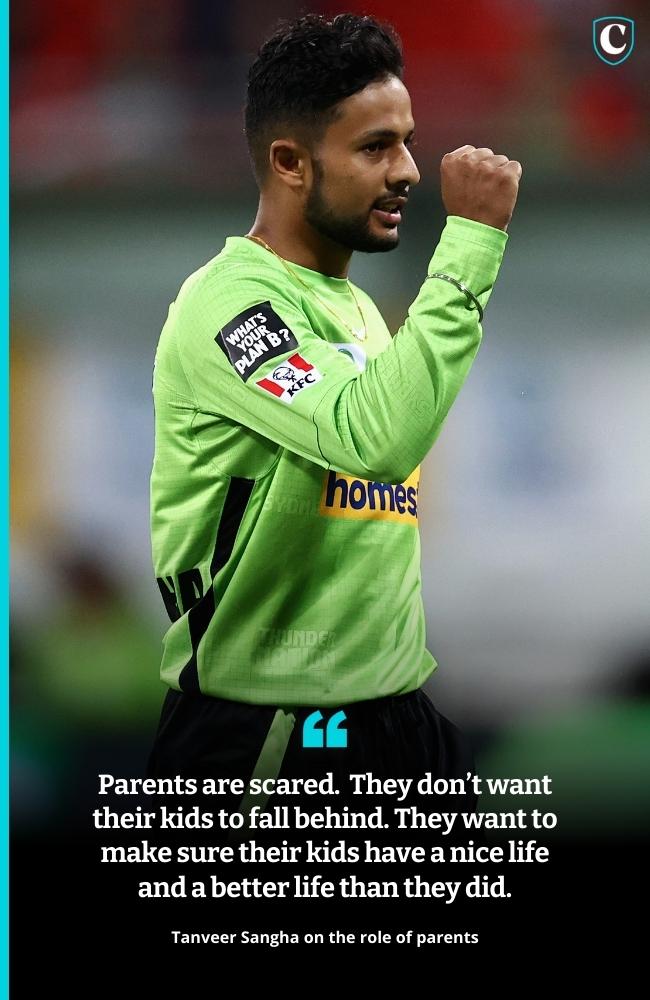

Both Jason Sangha and NSW spinner Tanveer Sangha (unrelated) pinpointed the importance placed on education in Indian immigrant families as one inhibitor on making it through the pathways system into the professional system.

“For South Asian kids, school is quite important,” says Jason. “You get to year 11 and year 12 and it’s crunch time – are you going to sacrifice two years of really studying hard for your exams or can we definitely see you going on to get that pro contract?

“A big part of that (drop across ages in the pathway system) is kids trying to really excel in their studies and then sort of pick up cricket towards the back end once school’s done.”

He sees it as no coincidence that the most prominent SAH men’s cricketers from NSW to have made it to the first-class system – himself, Tanveer, Gurinder Sandhu, Usman Khawaja, Arjun Nair and Param Uppal – all got a taste of professional success at a young age.

That success, and importantly their contracts, gave them the security required to chase the dream with the full backing of their parents. And Tanveer says it goes beyond school and into university, where education offers a secure pathway to employment more appealing to migrant parents who already took the big risk in packing up their lives and moving across the ocean.

“Parents are scared,” says Tanveer, “They don’t want their kids to fall behind. They want to make sure their kids have a nice life and a better life than they did.

“So they want to make sure they study and have all the opportunities and get to make the best career they can and the best life they can.”

The message he wants to spread as one of CA’s multicultural ambassadors is that you can have your cake and eat it.

“I see myself as a role model. I really want to encourage all the young guys in the pathway to really give cricket a good crack.

“I’m just trying to be the best I can be so parents can see that you can make a career out of this and you can have a successful and happy life playing cricket.

“And if it doesn’t work out, they can always go back to university. You don’t want to regret or wish ‘I gave cricket another year’. You can always go back to university, it’s always there.”

If the barrier to more SAH players making it through the system is indeed found to be the juggle of academic and cricketing pursuits, Allsopp is confident CA can find a solution.

“There’s plenty we can do,” he says. “It’s making sure our programs are really accommodating for people to be able to pursue their academic outcomes at a really important time of their schooling, but also support a bit of cricket development at the same time. I don’t think it has to be one or the other.

“If it’s proven that that is a barrier, a program that fits around both those commitments would be really important.”

CULTURAL BIASES AND COACHING

Khawaja has previously spoken of the need for more diversity at the elite coaching and selection level.

“If you have predominantly white coaches and selectors, they will gravitate naturally to the whiter community,” he said in 2022.

“That’s not because they are racist, it’s just because they grow up and see a kid who reminds them of their son or daughter. It’s a natural bias they have.”

Through his early years playing for NSW and Australia – and at times still now – he was been given backhanded compliments like laconic and laidback. It’s something Lisa Sthalekar says also she struggled with in her playing days.

Like Khawaja, she sees more diversity in coaching and selection as an important step.

“People used to ask ‘are they really engaged? Are they that passionate?,” Sthalekar says. “Because ‘they come across as quite not lethargic, not lazy, but just laconic, a little bit laidback – they’re not like us white Australians playing the game’.

“But I think most people that know Usman and myself are pretty passionate about what we do and Australian cricket.

“That was the perception back then and a hell of a lot has changed. But no doubt those types of things will still occur because there’s selectors or whatever it may be, selecting young athletes from different backgrounds who may not necessarily understand the cultural difference.

“That’s why you need diversity in all parts of Australian cricket, not just at a board level and not just in grassroots but actually at every step.”

At the grassroots level, Allsopp says there are plenty of people of SAH taking on coaching responsibilities.

But CA recognise progress needs to be made around the number of SAH coaches at the top end of town, in the elite pathways, first-class, and national systems and steps are being taken.

Among the current SAH players spoken to for this story, all of them stressed that what they wanted most from a coach was that they were highly skilled, regardless of cultural heritage.

Alongside the work being done to get more SAH coaches through to the top, education pieces have been put in place to teach coaches, selectors, and support staff about unconscious biases like those suffered by Khawaja and Sthalekar when they were coming through.

Again, among the players spoken to for this story, none felt this had been an issue that held them back.

“The best team being played on the park was my sense of it,” says Victorian opener Ashley Chandrasinghe of his journey through the system. “I didn’t really feel like there was any other motives for picking players or anything like that.”

“When I was coming through it was a little bit different (than Khawaja’s time),” says Jason Sangha. “I don’t think it was as noticeable or as bad as maybe Uzzie might have had it.

“Personally I don’t think there is much unconscious bias.”

Where Sangha believes more diversity within the coaching ranks would help is around understanding the South Asian mindset. Even then, he says that’s not necessarily down to cultural background as much as lived experience with people of the culture.

“You can’t really teach someone the cultural values you get instilled in you as a kid,” he says. “I can’t teach a coach that. It does make it a little bit more understanding, having someone that is aware of those things

“This might sound ludicrous, but there’s always going to be, especially with brown culture – you always want to do well at everything your parents put you into, whether it’s school or it’s cricket, that’s just how our genes are.

We’re a billion people over in India, you can’t make it anywhere by being mediocre. You got to stand out.

“The coaches who have done really well with kids of a different background have been understanding of that potential – I’m not saying every family is like that, this is just a stereotype – but there’s that understanding of maybe that family expectation.

“It’s hard to teach that, right? You’ve got to either be brown yourself to understand that or you have to have seen a lot of kids in the pathways, like (CNSW head coach transition pathways) Anthony Clark.”

ROLE MODELS AND A MATTER OF TIME

For Jason Sangha, seeing the likes of Khawaja and Sandhu breakthrough was a key part of his cricketing journey.

For Taveer Sangha it was the same when Jason, Nair and Uppal came through.

For Chandrasinghe? Not so much.

“No disrespect to Uzzie either, but my guy was Mike Hussey,” he says. “I just wanted to be him. Obviously you don’t look like Mike Hussey but there wasn’t any of that sort of mindset that I thought maybe I might not be able to make it. Yeah, my guy was Mike Hussey.”

Ditto for Hasrat Gill with Alana King.

“For me, Alana King was just another player that I loved watching,” she says. “Being a leg spinner myself, I love watching any legspinner go about their business.

At the same time: “It’s pretty cool she’s been someone that’s embraced that and has helped girls understand that there is a way for a South Asian person to go represent Australia

“I didn’t look at it any differently or anything but it was just pretty cool to see her go about it as well.”

Still, what Gill and Chandrasinghe – both a few years behind Tanveer Sangha in the professional system – have had to come to grips with is being role models themselves. While they didn’t need to see it to believe, they recognise the logic behind ‘you can’t be, what you can’t see.’

“I’ve probably not really even thought about being a role model for other kids,” says Chandrasinghe. “It’s sort of put on you in a way. I probably saw that after my (Victoria) debut.

“I had a lot of support from the South Asian community and that really opened my eyes about how many people are watching, and the kids that might be watching.

“Other South Asian players I’ve spoken to have said how proud they are that someone’s representing them. And even if that’s not really what I’m trying to do, I’m just trying to play cricket, for them it might be something different.”

For Gill, the responsibility has come on a little bit more naturally.

“There’s pride in that I’ve got the opportunity to represent two cultures and this really cool responsibility to showcase that no matter who you are, where you come from, you can do it,” she says.

FROM THE OVAL TO THE BOARDROOM

While there is an obvious gap between the numbers of SAH players in the pathways system and in the professional system, CA also signposted the need for improvement in representation across administration and at the board level too.

As of June 2023, around 18 per cent of staff working for CA identified as being of South Asian cultural background, but that number drops to only two per cent of individuals on Australian cricket boards and Australian cricket executive teams.

“You hear a lot with women and girls, you can’t be what you can’t see,” Allsopp said. “It’s the same with multicultural engagement in the game. You’ve got to make sure you’re able to see people that are in senior leadership administration roles in the game – and we know those are the roles of influence – that there’s people that are from my background at that level so I could aspire to that.”

Among the 10 key actions from the action plan was the start of its Multicultural Ambassador Program, headlined by SAH Australian cricket’s original two icons, Sthalekar and Khawaja.

As Sthalekar sees it, the ambassadors aren’t just representatives of the various South Asian diasporas. They are conduits between those diasporas and CA itself, and central to getting people from more diverse backgrounds into the decision making roles in cricket in Australia Allsopp refers to.

“When positions open or when vacancies occur on boards, even at clubs, you’ve got to actually pinpoint a group of people or a number of individuals that you want to be able to bring on board,” Sthalekar says.

“You can’t just open it up and hope the right people come forward. Sometimes those people aren’t aware, or maybe don’t feel that they can provide the skills that are required. It just needs someone to literally tap them on the shoulder and say, ‘you’d be wonderful in this role’.

“With the ambassador program, you’ve got people that you can go to and speak to and say do you know of someone that could fill this void or you know can you help us out in this area?”

THE WAVE IS COMING

What’s apparent among players, coaches and administrators alike is a firm belief that the wave will come.

This season has seen every men’s state side feature a SAH player in either List A or first class cricket.

Last year’s World Cup winning Under 19s boys side featured two SAH players – Harjas Singh and Harkirar Bajwa – and the Under 19s girls side that toured New Zealand featured three – Hasrat Gill, Ribya Syan, Samara Dulvin. Gill has gone on to play for the Stars this season, and Dulvin for the Renegades. Sianna Ginger, 19 and the daughter of Sri Lankan parents, has been a mainstay for the Brisbane Heat this season after starring at the Under 19 World Cup in 2023.

In late November, a NSW Colts hosted a Victorian Colts team in a four dayer. Yuvrav Sharma scored a ton in a Blues side that also features Ryan Gupta. Opposite them were Shobit Singh, Viswar Ramkumar and Dhanusa Gamage.

In December, the Under Age National Championships will be littered with players of South Asian heritage.

The wave is coming. It’s just a little overdue.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Khawaja rejects SEN interview after journo sacking

Usman Khawaja has declined a post-play interview with broadcaster SEN, seemingly in protest with the radio station’s decision to sack journalist Peter Lalor earlier this year.

Ashes alarm bells after Aussie collapse

The three-Test series in the West Indies was supposed to bed down Australia’s top three for the Ashes, but after day one England would be smiling from ear to ear.