Port Adelaide’s 150 Greatest Players in 150 years: Who has made the top five?

When The Advertiser ranked the top 50 Port players, there was one clear name for number one - Russell Ebert. Here's why.

Port Adelaide

Don't miss out on the headlines from Port Adelaide. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Port’s 50 Greatest Players: 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-21 | 20-11 | 10-6

- Port Adelaide’s 150 Greatest Players revealed

- How The Advertiser’s selection panel picked Port’s Greatest 150

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story was first published on May 26, 2020

If you ask Geof Motley what makes a great Port Adelaide player, he talks premierships, determination and dedication.

“You have to be successful,” Motley, now 85, tells The Advertiser, before borrowing a line from NFL coaching great Vince Lombardi.

“Winning wasn’t everything at Port Adelaide, it was the only thing.

“He’s got to have a certain level of ability but, more particularly, a work application that’s over and above the normal.

“They are prepared to be disciplined … and are committed to the cause.”

For the past four months, a selection panel, featuring club champions Brian Cunningham, Tim Ginever, Warren Tredrea and Bob Philp, historian Mark Shephard, media manager Daniel Norton and The Advertiser sports reporter Matt Turner, has been determining Port’s 150 greatest players, then ranking the top 50.

The concept was launched to coincide with Port’s 150th anniversary in 2020 – and continued as the coronavirus pandemic marred it and the season, prompting the AFL’s three-month hiatus, clubs to shed staff, games to be fixtured without crowds, the Power’s China match being scrapped and the Magpies’ withdrawal from the state league for the first time.

Now, the series concludes by revealing the five players the panel have elevated above the others: four-time Magarey Medallist Russell Ebert, war hero Bob Quinn, quadruple best and fairest John Cahill, nine-time premiership winner Motley and Champions of Australia star Sampson “Shine” Hosking.

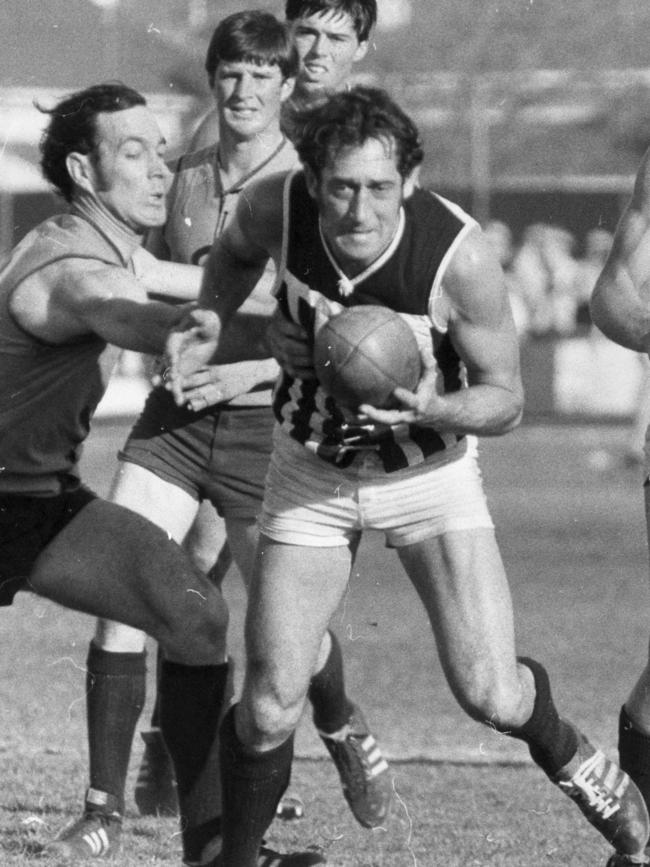

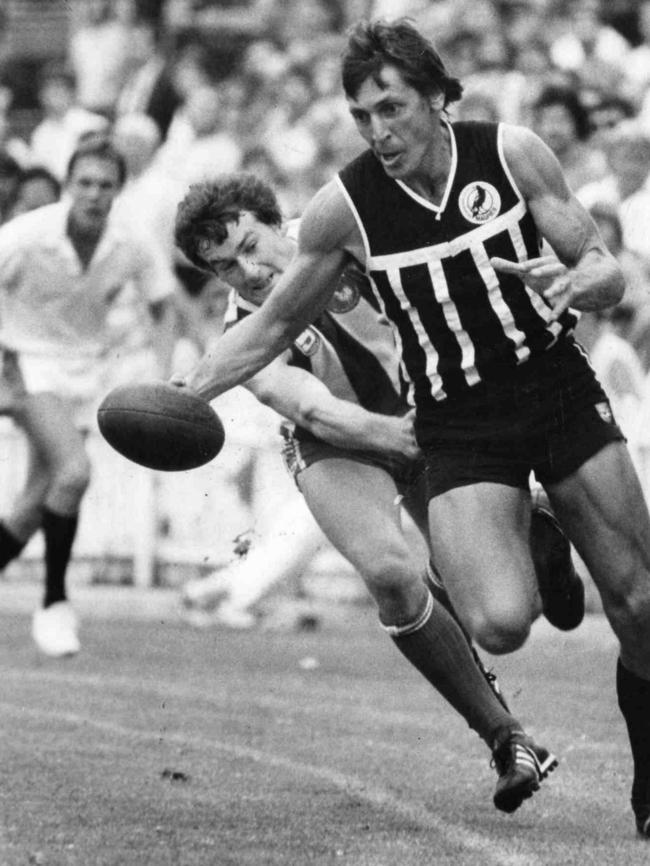

It will be of little surprise that Ebert, who has claimed more Magareys than any other player, as well as three flags and a record six Port best and fairests, has been chosen at number one.

When considering the selection criteria of on-field performances, impact on success, selflessness, longevity, achievements and passion for the guernsey, and judging everyone only on their playing careers at Port, former teammate Cunningham says Ebert deserves top spot.

“What made him so great was his determination and want to be the best, which never waned over his whole playing career,” says Cunningham of Ebert, who played a Port record 392 games from 1968-85.

“It was his individual brilliance on the field.

“It was his fairness in the way he went about the game and it was the fact that he is universally recognised by our supporters and opposition supporters as our best of the bests.

“When Russell took over from John Cahill as our captain (in 1974) … Russell adapted to it as if it was just another turn in the road and he became an even better team player.

“Russell was elite and set the bar high for all of us.”

Ebert emerged as a Port legend and one of SA’s best footballers after arriving at Alberton from the Riverland.

He was born in Berri and played for Loxton and Waikerie, before debuting for the Magpies at the age of 18.

“Where he began in 1968, as a talented and strong colt from the country, and where he finished as the best in the history of the game in SA, arguably together with Barrie Robran, is chalk and cheese,” Cunningham says.

Unlike Ebert, the other stars chosen in the top five grew up in the district: Quinn and Hosking at Birkenhead, Cahill at Seaton and Motley at Albert Park.

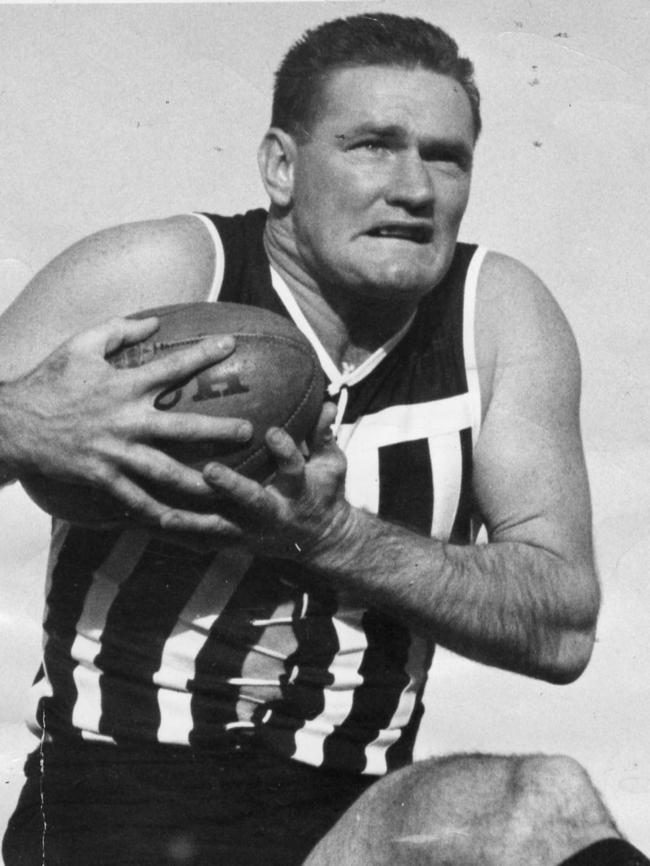

Quinn’s family home backed onto the Port river.

For most of his career, he would get to Alberton Oval by rowing a boat across the river with his father, 1904-05 Magpies captain John Quinn, then jogging or walking the rest of the way.

“Pop would go watch his son train then, if they were quick enough, they’d get a schooner at the Alberton Hotel on the way home before 6pm closing,” Quinn’s son, Greg, says.

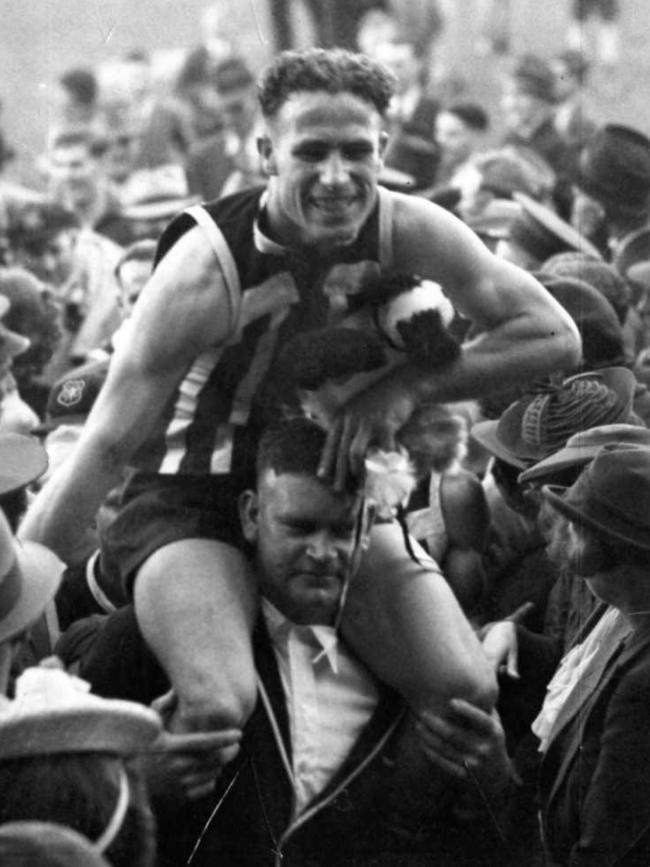

Quinn followed in his father’s footsteps by captaining Port, but went on to create his own legacy at the club.

The brilliant rover won the 1938 Magarey Medal, then was captain-coach of a flag the next year, before enlisting in the army in 1940.

In the Siege of Tobruk, in August 1941, Quinn, who was serving as a sergeant with the 2/43rd Battalion, sustained five leg wounds and facial injuries from enemy fire while placing bombs to defy German troops.

Quinn received a Military Medal for his bravery and leadership.

It was thought he might not play football again.

“They were going to cut his leg off it was that bad, but someone mentioned he was a renowned footballer and the doctor saved his leg,” Greg says.

Quinn recovered, became a lieutenant and resumed service, only to be badly hurt again after a bullet wound to his arm in Papua New Guinea in 1943.

His injuries did not stop him returning to football, wearing a leather strap to protect his arm.

Quinn’s legend status grew after adding two best and fairests for a total of four, as well as a second Magarey Medal in 1945, and also representing SA again.

“These days you have a small twinge in your calf and you think ‘oh, hello’, but here he is, they’re going to chop his leg off and he still wants to go to training, still wins best and fairests and still plays state football,” Greg says.

“He had every reason to come back and not do anything, just think ‘I’ve had enough’.

“I don’t know how he would’ve done it with those injuries and what he would’ve gone through.

“But he just loved football, loved the club and the competition.

“The hole in his leg, I used to see it when he’d wear shorts, but he’d never say ‘come and have a look at this’.”

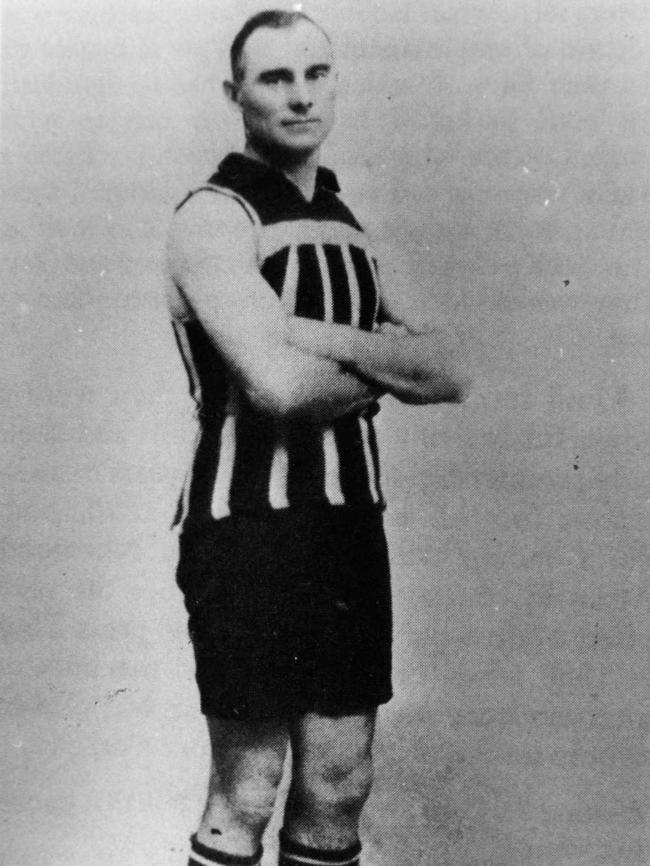

Hosking overcame a different type of adversity to become a Port great.

He dislocated his left elbow as a youngster after being thrown off a baker’s cart, which led to his father telling him not to play football.

Hosking resisted, lining up in Semaphore Central’s junior ranks for three seasons under an assumed name without his family knowing.

It was only when he was invited to play for Port in 1907 that he let his dad in on his secret.

The elbow injury plagued Hosking during his career – he dislocated it at least 14 times – but did not seem to hinder his performances.

In 1910, he won the first of two Magarey Medals and the club’s best and fairest, was second-best in its state league grand final victory and among the top performers in that season’s Champions of Australia triumph over VFL premier Collingwood.

Three years later, Hosking starred in Port’s national title success against Fitzroy and then was third-best in the 1914 SANFL grand final.

He earnt a second Magarey for his 1915 campaign, but was not officially awarded it until 1998 – 24 years after his death – after initially losing a three-way tie on countback.

Along with his elbow issue, Hosking also had to contend with being 167cm and about 57kg.

“He was small in stature but must have been big in heart,” Port historian Shephard says.

“He played well in the big games … and was one of the best footballers in the early 20th century.”

Hosking’s list of feats could be even longer and his name better known if not for World War I, which cost him three seasons at the peak of his career while Port was a powerhouse, because competition was suspended.

Cahill had a major sliding-doors moment before he even played a league match: what if he did not knock on the tin shed door at Alberton Oval?

Although he became one of Port’s most famous names, Cahill was originally aligned to South Adelaide, where his uncle, Laurie, was a star and Jim Deane was his hero.

Cahill boarded at his aunty’s in Sturt St in the city one night a week and used her address to play for the Panthers.

He won the league’s under-17 best and fairest for South but when Port general manager Bob McLean and coach Fos Williams found out he lived in the Magpies’ zone at Seaton, they went to Cahill’s place and invited him to the club.

“It was around October and I said ‘I’m never going to play at Port Adelaide, I don’t like them, South Adelaide is my club’ and I was prepared at that stage to stand out (of football) for 12 months to get a clearance,” Cahill recalls.

“But then it got to February or March and I said to dad ‘I just want to play’.

“I caught a bus down to Alberton Oval, walked down and knocked on a tin shed and the coach, Jack McCarthy, had played with Laurie and my dad at South Adelaide, so he knew the family history and said ‘we’d love to have you’.

“And that was that.

“I don’t know what I would’ve done if he said ‘no’.”

Cahill won the under-19 best and fairest that first year, then made the A-grade squad the next season and instantly felt at home.

“The first night (with the A grade), I walked into the room and ‘Chicken’ Hayes said ‘Johnny Cahill, it’s great to have you’,” he says.

“I felt like I belonged there with the way I was made to feel welcome.”

Cahill played 264 games, kicked 284 goals, was a one-time All-Australian and won four best and fairests and four premierships during his playing career from 1958-73.

The 1965 grand final success was particularly special because that was the day his son, international tennis coach and Port board member Darren Cahill, was born.

Some footy followers regard Cahill as the best player not to win a Magarey Medal.

He cites playing for Cowandilla in a Sunday afternoon association as a junior against older stars, such as future Port teammate John Abley, as crucial to his development.

Like Hosking, Cahill went against his father’s wishes to take to the field.

“Because I was a young kid, 16, dad said ‘you’re not playing’,” Cahill says.

“It was the only time I did anything wrong.

“I used to take my kitbag up to the deli, leave it there in the mornings and my uncle would come past on a motorbike and I’d jump on the back and we’d play football.

“It matured me mentally and made me tougher because you were playing against a lot of experienced players.”

Cahill credits his father, Vin, for helping to build his fitness via running sessions on an oval in what is now West Lakes and for instilling tremendous self-belief in him.

Later, Cahill became renowned for making his own players feel like giants during a brilliant coaching career that yielded a joint league record 10 premierships.

“I always saw the positive,” he says.

“If I played a bad game, I’d go home and all the next week I’d see myself playing well, attacking the ball, getting the ball first – imagery more than anything.”

Cahill also says Williams’ influence was enormous and the environment the club created during the 1950s and ‘60s got the best out of players.

Motley, who shares the record for most SANFL premierships as a player, along with Central District twins Chris and James Gowans, agrees.

“Most people hate our guts because we were Port Adelaide and we kept winning, but we won for a reason – we had an application that was better than theirs and a work ethic better than theirs,” says Motley, who won four of his flags as captain.

“The only thing in the world at that time was playing for a premiership.”

Motley barracked for Port as a youngster and his father, Arthur, played reserves for the club.

The first of his nine flags came in Motley’s second season, in 1954.

It launched Port’s unmatched run of six consecutive grand final triumphs.

“The celebration was powerful and then we got more potent,” he says.

“I think it was Bob McLean who said ‘nobody’s ever won five in a row or six in a row’ and that became our incentive.”

AFL sides now use buzzwords such as “connection” and “care” to describe the bond between players, coaches and staff, and believe closeness as a group is a key to success.

In Motley’s time, teammates spent Sundays doing drop-kicks – or “droppies” as he called them – together at Alberton Oval before heading to Largs to club doctor Bob Elix’s place, usually to celebrate victories.

“We got very close as a unit and became more of a family than a footy club,” Motley says.

When Williams stepped down as coach, Port offered Motley the position on several occasions and he rejected the offer each time.

But “they wore me down because they kept coming back”.

He steered the club to its sixth flag in a row in 1959, only to be sacked and replaced by a returning Williams two years later after successive third-placed finishes.

“If you don’t win premierships down there, they give you the bullet,” Motley says with a laugh.

Glenelg almost secured a coup by luring Motley to be its captain-coach ahead of the 1962 season, but his family’s Port history proved too big a hurdle.

“I said ‘in all probability, I’ll tick a few boxes and then come back and have a serious look at you,” says Motley, who also turned down offers to join Melbourne and South Melbourne.

“But I’d lost my father a couple of years before then and my mother said ‘your dad wouldn’t be happy and the family aren’t that happy’, so I told Glenelg I wouldn’t go.

“I’m glad that I did that and it’s important to me personally that I was a one-team player.”

Motley, who won the 1964 Magarey and four best and fairests, was forced to retire midway through 1966 due to a knee injury.

His team success means much more to him than his individual awards.

“The six in a row – that’ll take a power of beating,” he says.

“You can’t say it won’t be beaten because records are made to be broken but the odds of it happening are pretty thin.”

Today, the three living members of the top five remain associated with the club: Ebert works for Port, heading up its community youth programs, while Cahill and Motley are supporters.

In February, the trio was at Port’s gala dinner at Adelaide Convention Centre, which was a major event for the club’s 150th anniversary.

This year also marked a milestone for Cahill, who celebrated his 80th birthday last month.

He had heaps of calls from past Port people, as well as a lunch visit from Ginever and the club’s executive general manager, Matthew Richardson.

“The club has given me so much pleasure,” Cahill says.

“I’ve met so many good people through it.

“It’s been a really big part of my life and I’ve been lucky to be involved in it.”

Motley also says the club means a great deal to him.

“You’ll never take the Port Adelaide out of me,” he says.

Greg Quinn reckons despite his long list of achievements his dad, who died in 2008, would be embarrassed if he knew he had been chosen as Port’s second-greatest player of all-time.

“He’d try to deflect it to the younger players and how good they are and say ‘they’d eat us alive because they can run’,” Greg says of his father, who was the Power’s inaugural number one ticketholder and loved that Port stepped up to the AFL to take on the big Victorian clubs.

But Greg believes “for all his toughness, dad would be so proud” that his family has made such a significant contribution at a club that has just turned 150.

“He’d be absolutely over the moon the club had got this far, been so successful and had such wonderful players,” he says.

“I reckon he’d shed a tear.”