Anthony McDonald-Tipungwuti shares his story of growing up on Tiwi Islands and how he became an AFL star

Anthony McDonald-Tipungwuti enrolled in school to ensure he was allowed to play footy on Tiwi Islands. Then, a chance meeting changed his life forever. He shares his incredible story with Hamish McLachlan.

Essendon

Don't miss out on the headlines from Essendon. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Anthony McDonald-Tipungwuti is one of the most popular players in the AFL. Kids wear his number on their back and fans of all clubs love watching him play. But Anthony’s story isn’t like many others. He was born in the Tiwi Islands. His life was hard, and lonely, from the start. His father died when he was very young and his biological mother, Nola, left him when he was just eight months old. His gran, who then cared for him, died when he was 10. He was lost and directionless. Then a lady who he now calls Mum, Jane McDonald, walked into his life and changed everything.

HM: Is it Anthony, Walla, or Tippa?

AMT: Well I introduce myself as Anthony, but that’s the most formal of the three. “Walla” was my nickname growing up on the Tiwi Islands and I was nicknamed “Tippa” when I played at Gippsland Power. They didn’t pronounce my name correctly, so they wanted to make it shorter and went with Tippa. But I like Walla.

HM: Walla it is. Born where?

AMT: Born in the Tiwi Islands. It’s where I grew up for 16 years and that’s where my life started.

HM: Your story is extraordinary — and you want to tell it for the first time — all of it. Why?

AMT: I want to help people — kids of all backgrounds, whatever their circumstances. If I tell my story it might help them push through and find a way out of their darkness. It won’t be easy — it wasn’t and still isn’t for me — but with belief, love and help, you will.

HM: Your story has many layers and is very complicated. Are you sure you want to open up?

AMT: I am. I’m ready. I’m confident enough to now. It is my story, it’s the way my life has lived out from my side. People who know me saw the outside of me, but they didn’t know what was going on inside. I really struggled. For some reason I always had a bit of faith my life would change and that got me through my darkest times. Most people struggle with some part of their life. I was lucky to get a chance for a change in direction. It wasn’t easy, it’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done, and I am still working through things.

HM: Let’s go back to the start. At eight months of age your father passed, what do you remember of your biological mother, Nola?

AMT: She drank a lot and smoked a lot, so that period was pretty hard for her, losing dad. I was the one who was left behind. My two great aunties were our next-door neighbours. I was left and they say I was outside, crying, looking for my biological mum. They came, took me in and had some food for me.

HM: When you say left behind — what do you mean?

AMT: Nola abandoned me. She left me. Walked out on me.

HM: At eight months old? When did you see her next?

AMT: I’m not sure. After that my grandma put me under her roof and became my carer. My grandma was the one that looked after me from then. I didn’t see much of my biological mum. She lived on the same island, just up the road, but she wasn’t interested in me. Grandma also took on my brother and my sister for a bit, but I was the only one that she really took on at that point, all the way until I was 10. That’s the good bit I had with her. Grandma was strict.

HM: In what way?

AMT: No drinking, no smoking, no fighting in the house. If you did any of those things, you were kicked out. She was a really strong catholic woman. She took me to church, made breakfast for us, took us to school, clothed us. I wouldn’t be where I am now without her guidance. I might not be alive. I look back now and I’m really thankful for what she did for me until she died.

HM: Your grandma passed when you were 10?

AMT: She did. I had a really good home with Grandma and it was the best life I’d ever lived on the island, but then she passed. That’s when I found life very hard, from 10 right through to 16. That’s when everything fell apart, because she was the only person that I knew that really cared about me. She looked after me, she loved me, and after she passed away it was the hardest time I’ve ever gone through, trying to find that person that would do what grandma had done for me. It was a big struggle. I felt alone and without love or direction.

HM: You felt left alone for the second time in your life?

AMT: I did. I was hoping a family would take me in and really care about me, but again, I was pretty much just rolling around the streets doing whatever I wanted. That was the toughest time I had growing up.

HM: After your grandma died, where did you live? Who was feeding you and getting you to school?

AMT: I was living under the same roof at Grandma’s place. I had a mattress on the floor there, and my aunties were still there, so that was still home base. They had a family meeting to see where they could put me and see who I could go and live with. My oldest brother was who they decided on. I thought that it was going to be good, but he had a young child, a one-year-old.

HM: How much older is your brother than you?

AMT: Ten years older. I thought I was going to be able to live and be a kid, but I had to grow up quickly and look after his kid.

HM: Where was your brother and the child’s mother?

AMT: They’d be going out to the club, drinking, so I was at home looking after my nephew.

HM: At 10-years-old?

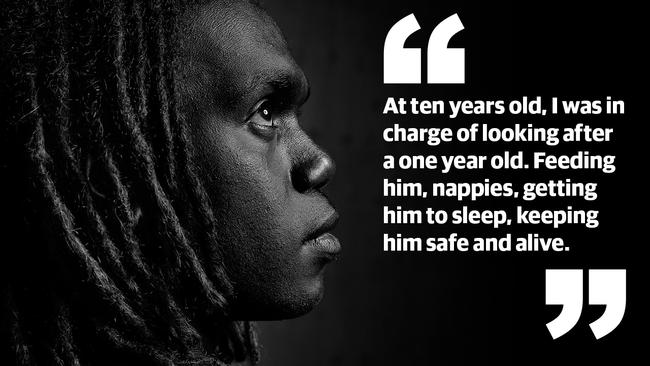

AMT: Yep. I was in charge of looking after a one-year-old. Feeding him, nappies, getting him to sleep, keeping him safe and alive.

HM: Did you have any idea what you were supposed to be doing?

AMT: No — no idea. If he was crying, I’d try to get him to stop with some food if there was any about. And change his nappies and get him to bed at night and out in the morning.

HM: Mind blowing. Did you stop going to school?

AMT: I was in and out of the school. I couldn’t go if I was alone with my nephew. It wasn’t really important at that time. There was a lot of bullying going on so I didn’t mind not going.

HM: Bullied on what front?

AMT: Being a loner. I was always by myself, trying to look for friends. They’d constantly call me the “lost dog”. I didn’t fit in with most kids on the island, so I was always the one left out. That’s why school wasn’t really important to me.

HM: How were you in terms of reading, writing, and speaking English? English was the language of the school, but you weren’t proficient.

AMT: English wasn’t an everyday thing for us. You learn it, then go home and talk Tiwi. I didn’t enjoy school because I thought I was dumb. I would make a mistake at school and then everyone would start laughing at me, so I was too scared to say anything anyway.

HM: It was easier for you not to go to school?

AMT: I’d skip school all the time. I’d roam the streets and, in the end, I was on a collision course with bad things as there was no direction, no guidance and no way out in my mind. I was a bit scared of what was ahead.

HM: And that’s from when you were 10 through to 16?

AMT: Yep.

HM: You’re not going to school, roaming the streets, your English is poor, you can’t really read, and then, by chance, you meet someone who would change your life. How did you meet Jane McDonald?

AMT: We had a new school on the Island called Tiwi College, and I enrolled there in the first year only because they had a footy program there, and unless you enrolled, you couldn’t play footy.

HM: Attend classes to play footy?

AMT: Don’t turn up for weeks, but as soon as there’s a footy comp coming up, go to school! We were in the bus going to the waterhole, and we saw my (now) mum (Jane McDonald) and my (now) sister (Nikki) cleaning the school. We wondered what these people were doing, cleaning our school — are they crazy?

HM: That was the first time you’d seen each other?

AMT: Yes — the first time I saw mum and my sister. Mum was helping out my sister, Nikki. She was a house parent in Tiwi, and Mum was helping with some sport, working with the Tiwi Bombers.

HM: And that’s when you bonded?

AMT: That’s where I got close to them. I had a training session up in Darwin, and I forgot my socks. I was scrambling looking for some socks, and I said to mum, “I don’t have any socks to train in”. My coach had said to me, “If you do that again, you’re not going to play”. I was embarrassed because everyone was looking at me. I was 16 at the time. Mum said to my sister “Take your socks off and give them to Anthony”. That was the first moment for a long time where I felt I had someone that really cared about me.

HM: Which you hadn’t had for six years?

AMT: Not since my gran had died. Gran was the first and only person who had ever cared for me, and who I had felt loved by. I’d had no affection since then. It was then I wanted — and in a way I sort of knew — that mum was the person who was going to take care of me for the rest of my life.

HM: When your sister, Nikki, gave you the socks, how long had you known each other?

AMT: A month.

HM: You took the socks from Nikki, and you felt loved and included and wanted, which you hadn’t felt for a long time. How does the conversation go from, “thanks for the socks” to, “I want to live with you?”

AMT: Me, CK and John Pierre … two mates of mine, used to follow Mum and Nikki and go wherever they went when they were in Tiwi. They were on Tiwi living at Tiwi College.

HM: Jane — you were living on the Island permanently, or for a short period to try and find yourself?

JM: Just for a short period. My husband Jim had passed away and it was a time to get away and clear my head.

HM: You were up there just helping out where you could.

JM: Yep, living at Tiwi College. For my food and board, I took sports classes and nutrition classes. That’s what I did at Chairo Christian School at home. I had the full backing of Chairo at that time, because Jim had worked there at different times. These three kids, Anthony, John Pierre and CK just followed us wherever we went.

HM: What were you wanting Anthony?

AMT: Looking back, probably love. Affection, touch, that feeling of connection. It was heading up to Christmas break, and I asked Jane whether she’d take us in for Christmas!

HM: What did you say?

AMT: There was a post at the school, out the front, and I hid behind it, waiting for Mum to come past. I stuck out my head and said “Would you take us to Melbourne for Christmas?”

HM: You stuck your head out, said it, and then ducked behind it again because you were too scared the answer might be no?

AMT: Yeah. I was afraid to ask, but I just had to. I felt so comfortable with Mum, and knew I had to ask.

HM: What was the answer?

AMT: Mum said she’d ring her kids at home and ask them if she could bring us to Melbourne for Christmas. Then Mum went to China for a week on this trip she had promised the school she would go on, and I didn’t talk to her for a week. I was so upset. I felt she had left me for good.

HM: Abandoned again?

AMT: Again. Same thing. I had this person that I really trusted, that really cared about me, and now she’d left me again.

HM: You had a fear of getting close to people?

AMT: Yep. Mum asked Nikki what was going on with me, and she said: “He doesn’t think you’re going to come back”.

HM: Nikki said Jane would come back, but you didn’t believe her.

AMT: No. I thought, “This is how it happens — this is how my life is. Nola left me. Gran left me. Now Mum has left me again!” Nikki said to me, “Mum would never do that. You’ve got to trust her — she’ll come back”. I was 50-50 at that time. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to trust Nikki and have my heart broken again. What if she didn’t come back? Again, Nikki assured me she would, but I just expected her not to.

HM: Jane, you went to China, and you landed at home, and then went back to the Tiwi?

JM: I landed, did what I had to do for a day or two at school, and then went back to the Tiwi.

HM: When you saw Jane again, did you start the chat again?

AMT: Yeah. She said we could go with her to her home in Gippsland and have Christmas.

JM: They didn’t have any ID to get tickets to get them on a plane! We asked for their birth certificates from the school, but they wouldn’t give them to us, so we had to do this dummy ID up to get them on the plane.

AMT: We’ve still got it!

JM: I asked a cousin of Anthony’s, “Who is the guardian who looks after Anthony?” And he said, “Anthony is in charge of himself”. At this stage, I didn’t even know that his biological mum, Nola, existed.

HM: So where was Nola at this point?

AMT: She was on the island.

HM: How much contact did you have?

AMT: The only time I would go and see her was if I was hungry. I’d go to the club where she was drinking and ask her for some food. I’d get a drink and a packet of chips.

HM: How often would that have been?

AMT: Four times a week.

HM: Four times a week you’d be starving and you’d go to see if Mum would give you something to eat?

AMT: Yep, or anyone for that matter. See who had a bit of food to spare for me.

HM: Because there wasn’t much at the home?

AMT: Nothing. My stepdad, John, was living with Nola at the time, and he was the only one that cooked at home. I would go around there whenever I could, because I knew he could cook a good meal and he would give me one. That was the only time he’d look after me, when I was hungry. He was a happy drunk, worked, had a good job, so he was someone I used to look up to. He would work and then go and enjoy himself by having a few drinks. The rest of the family, when they drunk, they were very violent. He was the only one that made my life happy. The others didn’t.

HM: That’s bloody sad. You got to Victoria for Christmas. How was it?

AMT: It was amazing. We were so excited to be there. We kept to ourselves a lot as we didn’t want to intrude and were a bit shy with Jane’s other kids there. CK and I just stayed upstairs, listening to music for a lot of our stay. We were upstairs listening to Akon (American singer) the whole time — over and over. The only time we’d come downstairs was when we got the chance to go and ride the ride-on mower! We mowed a footy oval out the back.

HM: Had you ever been given a Christmas present before that trip?

AMT: No. Never.

HM: You had seemingly stumbled into a very different environment — from days on end where you didn’t get much to eat at all, to Christmas lunches, three meals a day and presents from people you hardly knew.

AMT: Yes, it was very different. From starving for a day or two at a time, to Christmas with this amazing family who seemed to care for me.

HM: Where you were welcome. And you were hugged.

AMT: Yeah. Yeah, I was. Mum was the first one that cuddled me since Grandma died. Gran was the first and Mum was the other. That was the point that I knew someone cared about me. That was when I knew someone in the world wanted me to be OK. I had found the person that would give me a second chance at life. I just feel so lucky that I met Mum.

HM: You didn’t feel like anyone cared for you at all before then?

AMT: No — I didn’t think anyone cared for me and I didn’t think anyone ever would again.

HM: Gee. How did you go from Christmas, Akon, lawnmowers, to, “Can I stay here forever?”

AMT: I asked Mum if I could stay. And she said yes. Then we had a tour of Chairo Christian College in Gippsland, where mum worked, just to go and have a look. Her son Michael, and daughter Nikki were both teachers there.

HM: Did you ring anyone at Tiwi to see if you could stay?

AMT: I didn’t think I needed to. No one would have cared. No one probably even knew I had gone. I wasn’t around, so it was probably one less problem. Out of mind, out of sight.

JM: I made him go back and ask his Aunty, Augusta. She said it was a good opportunity.

Originally published as Anthony McDonald-Tipungwuti shares his story of growing up on Tiwi Islands and how he became an AFL star