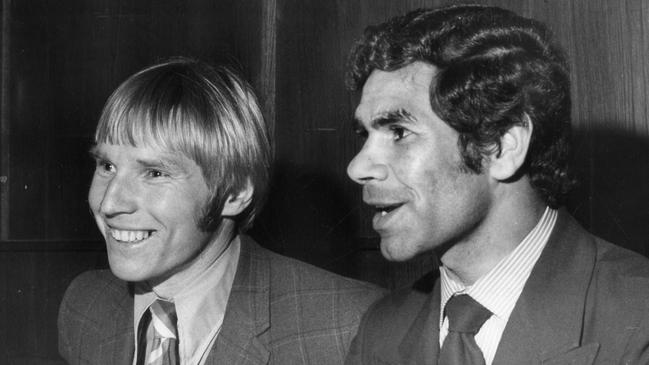

Syd Jackson and Lee Adamson were central figures in one of footy’s early race rows. Five decades on, they share their stories

In 1970, Syd Jackson was reported for striking Lee Adamson. The defence used at the tribunal sparked a 50-year race controversy - but it wasn’t true.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

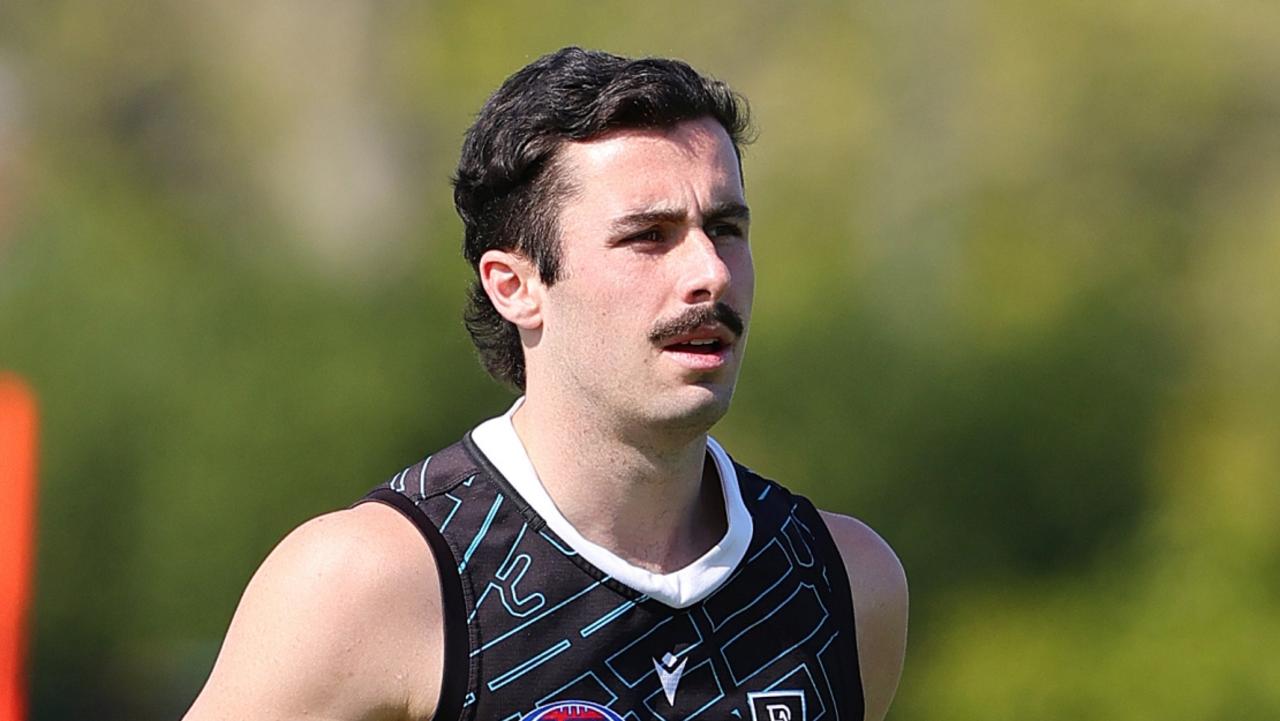

Lee Adamson was a tough, dashing Collingwood defender in the late 1960s and ’70s, who rarely showed outward displays of emotion.

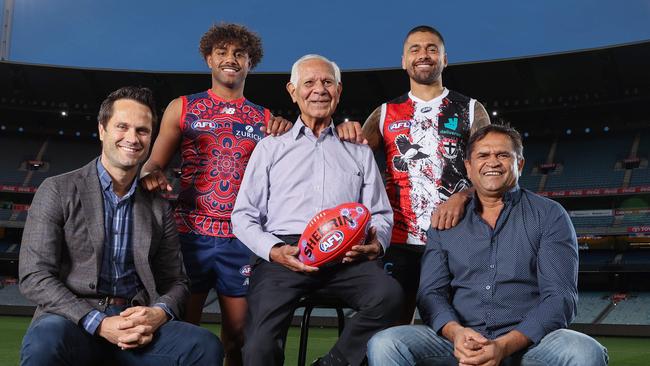

But five decades on from his 96-game VFL career, the 75-year-old was brought to tears at a reunion with Carlton’s Indigenous great Syd Jackson as the one-time adversaries met for the first time since being a part of one of footy’s first big race controversies.

In a tribunal appearance following the 1970 second semi-final between Carlton and Collingwood, Jackson said he had struck Adamson because the Magpie backman had made a racial slur towards him.

Adamson hadn’t.

Watch The 2021 Toyota AFL Premiership Season Live & On-Demand on Kayo. New to Kayo? Try 14-Days Free Now >

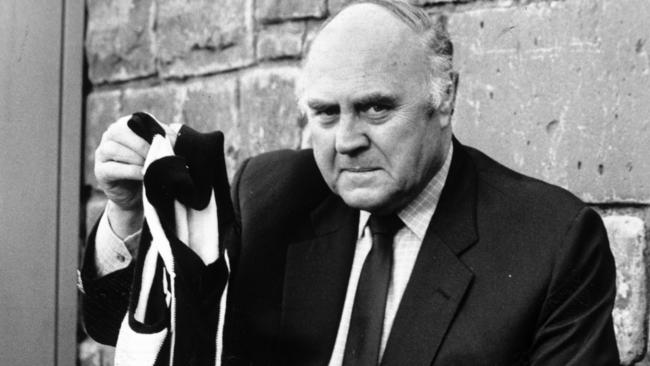

In Carlton’s desire to beat the charge and keep Jackson’s finals hopes alive, then Blues president George Harris instructed him to present an “extreme provocation” defence — even if it wasn’t true.

Jackson, now 77, has unquestionably encountered all manner of racism throughout his life and during his football career, but not in this instance, and never by Adamson.

It would take more than 20 years for Jackson — one of the AFL’s most revered Indigenous leaders and an Indigenous Team of the Century member — to correct the wrong, saying Adamson hadn’t racially vilified him.

It was only recently, just before Melbourne’s lockdown, that the two players were reunited by the Herald Sun and Jackson was able to finally apologise to Adamson in person.

While Adamson has never wanted to dwell on the incident, and doesn’t blame Jackson for what happened, the reminders have never been far away.

Even when Collingwood’s Do Better Report into “systemic racism” at the club was leaked earlier this year, he had to defend himself when one media organisation erroneously stated that he had racially abused Jackson.

He wrote to the organisation to right the wrong, but never received a reply or a retraction.

But Adamson’s tears when he met Jackson recently were about injustices far more important than his own.

Four of Adamson’s 11 grandchildren are Indigenous, and he wants them to grow up in a world where they don’t have to experience what Jackson has had to endure in his journey.

EARLY YEARS

Adamson grew up in a loving family in Greensborough, on the outskirts of Melbourne, with his dad a local footy legend and his mum “a feminist before her time”.

Jackson doesn’t know his actual birthdate, doesn’t know his real birth name, and he never really knew his parents — camel trainer Scotty Tulloch and his partner Amy — or his older sisters Marjorie and Jean.

He saw his sisters again many years later, but they met almost as strangers.

Born near the gold mining town of Leonora in Western Australia, Syd was one of the Stolen Generation, taken from his family when he was only three years old.

“I was thrown on a truck,” Jackson explained. “I was going down town to have an ice cream and the truck just kept going.”

Jackson was moved about on several occasions before he ended up at Roelands Mission, near Bunbury, where he remained until he was old enough to leave at 15.

It was almost “slave labour”, with the children forced to work for hours before and after school.

“You would be out of bed at six in the morning, milk the cows, feed the pigs and you would also do the cooking and housework,” he said.

Footy was Jackson’s release.

“The mission kids loved it,” he said. “The town kids … couldn’t catch us … barefoot and all.”

Jackson made his senior debut for South Bunbury at 16 and within a few years he was playing with East Perth in the WAFL, winning the club’s 1966 best-and-fairest.

He was invited to join Carlton in the VFL, even if he couldn’t get a clearance in his first year in Melbourne. That meant he was the team’s runner in 1968, when the Blues won the premiership.

In 1969, the highly-skilled Jackson burst onto the VFL scene as the competition’s only Indigenous player that season, with the kids left behind at Roelands tuning in on the radio to listen to his exploits.

THE INCIDENT

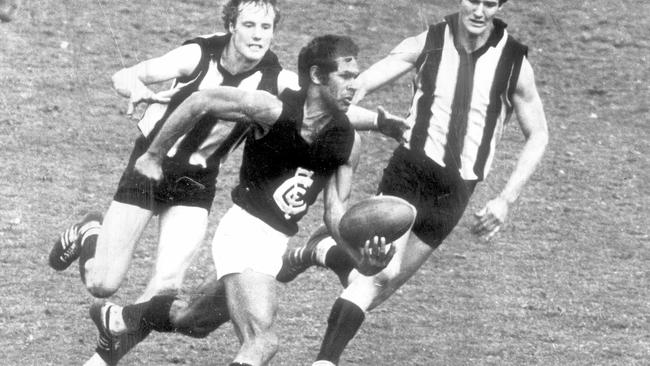

Adamson was in his fifth VFL season with Collingwood when he played on Jackson the first time — in Round 8, 1970.

“I remember because he was cutting us up,” Adamson recalled.

“I was a verbaliser, that’s the way I played. I would be saying to Syd: ‘Are you going to get the ball or are you going to hang out?’. I did it to everyone. If someone whacked me, then I got whacked.”

But Adamson’s verbalising was never about race.

The incident that would forever link the pair came in the 1970 second semi-final.

Carlton captain John Nicholls took a mark just outside the goalsquare, but the ball spilt free.

Jackson went to pick it up when Adamson threw his boot out at his opponent’s outstretched hands.

“He went to pick it up and I went bang,” Adamson recounted. “I gave him a little touch up on his hand, which wasn’t very nice.

“So he clipped my jaw and I went down like a bag of s---.”

Jackson added: “It was just a spur of the moment thing and I was reported for it.”

Collingwood won the game by 10 points to advance to the grand final. Jackson had been reported for striking, and Adamson for charging him in an earlier incident.

Their next showdown would be at the tribunal.

TRIBUNAL

Harris and the Blues knew if they could plead provocation, they could potentially save Jackson’s season.

“Carlton made up a story that I was provoked,” Jackson said. “It wasn’t anything against you, Lee, but they were very concerned I would miss (the grand final).”

“(Harris) said to me to say (Adamson) called me ‘a black bastard’. I was at the tribunal and they (the Blues advocate) said: ‘Syd, did he (Adamson) refer to the colour of your skin?’. I said, ‘yes, yes, yes’.”

Adamson and Collingwood were not happy he had been wrongly accused of making a racist comment.

“I knew I hadn’t racially abused Syd,” Adamson said. “I’ve never been a racist.

“They pulled a story to get him to play in the Grand Final. He (Harris) was a cunning bloody bloke. I didn’t like George much anyway.”

Five decades on, Adamson doesn’t hold the incident against Jackson, although he has previously said he despised Harris.

“If I had been in the same spot as Syd, I probably would have gone to any lengths to play in a grand final, too,” Adamson said.

“I copped it a bit (after the tribunal hearing). I would always be reminded of it over the years. But I knew that my mother and father brought me up the right way.

“They always said race, colour and religion never mattered. That’s how I’ve always lived.”

As much as he still harbours some guilt, Jackson believes if he hadn’t been told to go with Harris’s ruse, he might have been suspended and missed the grand final.

“I got a sympathy vote,” he said.

Both players were cleared, but the stigma stuck with Adamson.

Jackson went on to kick six goals in a blistering performance against St Kilda in the preliminary final.

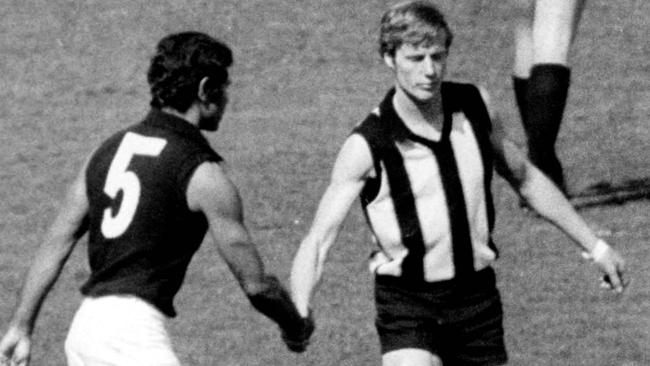

A rematch with Collingwood — and Adamson — beckoned.

1970 GRAND FINAL

Jackson can still reel off the exact crowd number of the 1970 grand final crowd — 121,696 — like someone else might reel off a phone number.

It remains the greatest attendance at a VFL-AFL match and was one of the most famous premiership playoffs.

Adamson shook hands with Jackson before the start of the game, but neither said a word to each other.

“We shook hands and that was it, we just played,” Jackson recalled.

“To both of our credit, there was no hijinks. We had been through that (tribunal) stuff,” Adamson said.

“You didn’t want to do anything stupid and have to live with that for the rest of your days.

“I tried to stop him from kicking a goal, which I failed at, because he kicked one and he gave another off (to Ted Hopkins).”

Collingwood’s Do Better report into claims of “systemic racism”, released earlier this year, cited a moment in the game when Jackson was booed by Magpies supporters.

The report referred to a Channel 9 commentator who said: “I don’t like this crowd booing. Bad sportsmanship from Australians to boo on an occasion like this because this fellow (Jackson) is a coloured man, we know, but he is entitled to every bit of respect that anybody’s allowed.”

Jackson says if there was booing that day … “I don’t think they were booing me.”

“I don’t know whether it was just me or whether it was directed at Carlton.

“Anyway, booing in general used to just fire me up even more.”

HALFTIME ENDEAVOUR

Collingwood led by 44 points at halftime, or as Adamson puts it, “by six goals eight”.

That referenced the Magpies’ wayward kicking for goal, even if they looked to have the game well within their grasp.

As champagne corks were being popped by eager Collingwood supporters, there was plenty of action in the Carlton rooms.

Blues coach Ron Barassi was about to turn the game — and the code — on its head, urging his players to “handball, handball, handball” and to take risks.

Jackson recalled the master coach trying to emphasise three key points: “Endeavour, encourage and enthusiasm.”

“‘Barass’ said, ‘How am I going to explain this to you, Syd? Endeavour, it’s like Captain Cook (The Endeavour had been the ship Cook sailed to Australia in 1770),” Jackson said.

“I said, ‘Yeah, Barass, he was the bastard that pinched the land off us’.”

Jackson’s joke on a serious subject loosened the mood. He likes to think it played a small role in Carlton’s stunning second-half comeback.

“Some of the guys had a giggle and other blokes started laughing,” Jackson recounted.

“Even Barassi laughed. I think it broke the tension a bit. Maybe it helped us, I reckon it did, anyway.”

Ted Hopkins came off the bench and went on to kick four goals in the second half.

Adamson recalled of the second half: “They (Carlton) were running all over the joint and coming down in waves. I didn’t know whether to run up to meet them or stay back on Syd”.

Carlton swept over the top of a stunned Collingwood, winning a memorable premiership by 10 points.

Jackson was a VFL premiership player and he would go on to win another flag two years later.

This was a second grand final heartache for Adamson, who also played in the Magpies’ one-point loss to St Kilda in 1966.

“You had two chances in grand finals, Syd, and you got two out of two,” Adamson said. “I had two chances and got nothing out of it.”

THE FUTURE

Adamson always admired Jackson’s journey from afar, despite their differences in 1970.

Both dearly love watching the modern wave of AFL Indigenous champions, even if they concede the game — and society — has a long way to go to right the wrongs of the past.

Adamson has become a loving grandfather to four Indigenous children: Keysha (13), Shianne (11), Shyleeka (10) and Steven (8).

“Their mum ... was unable to take care of them,” he said.

“My daughter-in-law Kate is a social worker up in Bendigo and she promised to look after the kids.

“They already had three kids of their own, so the house is active, but they have lots of fun.”

Jackson’s face beams when he hears Adamson’s heartwarming story for the first time.

“That’s just a fantastic story,” Jackson says.

Tears streamed down Adamson’s face.

This wasn’t about what happened to him 51 years ago; it’s about what has happened to Indigenous people across the centuries and what still happens too frequently now.

“I am not angry at Syd; I understand what he did (at the tribunal),” he said.

“But I am bloody angry about what we have done to Aboriginal people in this country.

“We took their land and gave them nothing.

“We never got that history when we were growing up. We only got the white man’s history.

“We have still got a long way to go as a society.”

At that point, Jackson’s hand reaches across the table to shake Adamson’s hand, just as they did before the 1970 grand final.

Their reconciliation is complete; their shared ambition for change stronger than ever.

More Coverage

Originally published as Syd Jackson and Lee Adamson were central figures in one of footy’s early race rows. Five decades on, they share their stories