How the AFL’s Illicit Drugs Policy works and why some think it should change

The public battle over the AFL’s Illicit Drugs Policy continues — with hard line commentators wanting a major shake-up. We look at the ins and outs of the debate.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The public battle over the AFL’s Illicit Drugs Policy (IDP) comes down to two words: zero tolerance.

Hard line commentators and people around football want the drug code beefed up, so a player found to have taken an illicit substance is named and shamed as a form of public penance.

But the AFLPA will always stand by its “behaviour-change” system designed to help players through any drug problem before it becomes a serious addiction.

An updated version of the AFL IDP is imminent, so here is how the current policy works and the two sides of the debate.

HOW DOES IT WORK?

The current IDP was introduced in 2005, with the AFL the first Australian sport to introduce a league policy aimed at illicit drugs.

Before then, penalties for recreational drug use were handed out by clubs, with a boiling point emanating in 2004 when Laurence Angwin was sacked and Karl Norman suspended and fined for showing up to training under the influence of party drug ecstasy.

Over the years it has been adapted, most notably in 2015.

Under the current policy when a player tests positive, uses or deals, possesses or refuses to undergo testing for illicit drugs, they receive a suspended $5000 fine, are sent for counselling and receive targeted testing.

On that first ‘strike’, only the club doctor is supposed to be told, not other members of the club, a part of the policy designed to get the player the best treatment and help as they can without adversely impacting their on-field or selection chances.

If a player gets a second strike, they are hit with a four-match ban, a $5000 fine and not only is the club told, but the public is made aware.

This has changed from the initial policy, when players were not named publicly until a third strike.

A third strike leads to a 12-match suspension.

The strikes have to come within four years of the previous one to be considered a second or third detection.

Since the policy was revamped in 2015, no player has been named as having two strikes to his name.

From the introduction of the IDP, only Hawthorn player Travis Tuck has received three strikes.

Some players are inadvertently named and shamed, such as when videos emerge of them partaking in illicit substances.

Players like Shane Mumford, Jack Ginnivan and Bailey Smith have been caught through this method and it is assumed they were given a first strike.

Others can receive a strike when they run afoul of the law.

Tyson Stengle, Elijah Hollands and Brad Crouch are players in recent years who ran into trouble with police and the courts for possession, and similarly, those players receive an IDP strike.

On all of those occasions, the players were handed league suspensions, often labelled for “conduct unbecoming”.

A key differential in drugs penalties comes between the AFL’s IDP and its cousin, the Anti-Doping Code.

The ADC is run in conjunction with the World Anti-Doping Agency and focuses on game day testing, to curb players gaining an advantage by taking a substance before matches.

Players are chosen at random after matches to be tested by officials, who can be forced to sit and keep an eye on the player post-match as they wait for a sample.

Those bans can be career-crippling, with Melbourne utility Joel Smith handed a ban of four years and three months in October, 2024, for five violations stemming from a positive test to cocaine on a matchday in August, 2023.

THE POLICY CRITICS

Those unhappy with the IDP believe it contains loopholes that mean the game turns a blind eye to players taking drugs.

Given the first strike is not public and the only member of the club outside the player who is aware is a club doctor, critics have seen this as a free swing for a player to escape sanction.

Accusations emerged last year that players would self-report drug use to their doctors, who would advise them not to play that weekend, to avoid the risk of a game day test that could lead to a big ban.

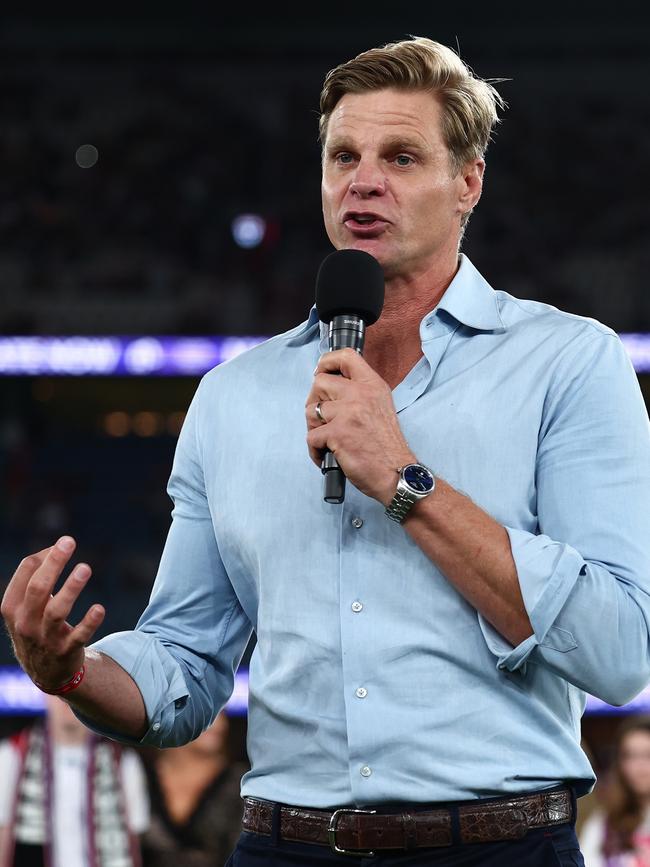

Nick Riewoldt, who captained St Kilda and saw his former teammate Sam Fisher jailed last year for drug trafficking, has labelled the current code as “outdated”.

“Drug-related societal issues have moved so far since that code was introduced,” he said in May.

Former Collingwood president Eddie McGuire has often criticised the policy and claimed players fall into drug use that can lead to further issues, like blackmail towards match fixing.

“If you self-report you get nothing. If you get caught on matchday because you took it one day too late or they have better testing, you get put out for life. You get four years and you are cooked. And if you get your photo taken (taking drugs) you get rubbed out for two weeks,” McGuire told Footy Classified last week.

“I believe in what the AFL and the PA has done over the years as far as the empathy and the medical approach to it. But we are long past it. The community has said, enough, we have to have some parameters.

“We can’t just keep going down this path, it is not working.”

Collingwood champion and ex-coach Nathan Buckley has said the IDP “enables illicit drugs use”.

Those critics slide towards a zero tolerance approach.

Melbourne captain Max Gawn said in March last year, the “deterrent is not there” on a first strike and “something needs to be bigger potentially on the first strike”.

It’s safe to say the AFLPA does not agree with the critics.

THE POLICY PROTECTORS

Now departed as AFLPA CEO, Paul Marsh was clear last week when asked about those that would like to see players penalised further in the policy update.

Marsh told media on Tuesday the IDP was a “behaviour-change approach” and experts the PA worked with had more information about how it worked than those who sit behind desks on footy panel shows.

The PA has chosen not to release number figures on those caught up in the strike system but have watched closely players who have been aided by the help-first, name-later system.

They believe countless young people have been saved from a spiral through counselling and intervention.

By supporting players instead of publicly raking them over the coals, the PA believes the policy can prevent serious harm.

Some players, such as Smith and Ginnivan, don’t get that choice, thanks to videos sent out on social media.

When prompted about zero tolerance, Marsh doubled-down on Friday, asking: “What’s the alternative? We just kick them out?”

“I don’t think people who have that view (zero tolerance) have thought that through,” he told SEN.

“There are people on the flip side who say ‘We need to do more for our past players’, well what we will have (with zero tolerance) is a whole lot of past players who have drug issues that no-one has supported and potentially have bigger issues.

“Our opportunity is to get them in the system, work with them. I know of a lot of players who have benefited with it and I’m comfortable with where this is going.”

For 20 years, critics in one corner have called for harsher penalties, and others have backed in the help-first policy.

Given it appears likely there won’t be dramatic change coming under the revised document, those two corners will remain split apart.

More Coverage

Originally published as How the AFL’s Illicit Drugs Policy works and why some think it should change