Dermott Brereton reveals horror injuries gained during career

There’s no doubt AFL Hall of Fame member and Hawks legend Dermott Brereton will always be known for his toughness, but that reputation comes with a heavy price. This is the one stat that truly reveals his career’s toll on his health.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s generally once a year that Dermott Brereton will pull his premiership medallions out of a safe. And it isn’t hard to guess that it’s usually around grand final time, considering he won five of footy’s ultimate honours.

“Each year when it’s finals time and we have jobs and people ask can you speak to this group or luncheon, I’ll take them out then,’’ Brereton says.

“Last year was 2019 so it was 30 years since 1989 (when Hawthorn beat Geelong) and I took those medallions out and took them wherever I’m speaking to show people first hand and close up what they look like.

“We play for so much more than a medallion, but that’s the physical representation of a life’s work. I’m always appreciative of just how fortunate I was to land at a great club that was run really well, they recruited the right players, the right coach and made it all come together.”

Brereton was truly part of a golden era at the Hawks, winning four flags in the ’80s and the last one in 1991. There were also five night premierships on top of that.

Nicknamed The Kid, the boy from Frankston played his first game in 1982 and his last with the Hawks in 1992. He went on to play cameos at Sydney and Collingwood but the bullocking curly-haired blonde centre half-forward will forever be remembered for his extraordinary feats in brown and gold out of his 211-game career.

The AFL Hall of Fame member was known for his toughness and never-shirk-a-contest attitude. But it came at a heavy price.

He can’t run anymore, or take to the water to surf — painful reminders of a hard-nosed football career.

He underwent his 26th major surgery — a back operation to fix his spine — in February. At the time he was in so much pain that each morning he had to roll onto his stomach, then slowly slide off the edge of his bed until he could push himself upright with his arms.

But the 56 year-old father of two has no regrets.

“I’m seven months now since the back operation and I’m getting a lot better and a lot stronger,’’ Brereton says.

“It was quite a serious operation that’s for sure. It’s been explained to me just how difficult this type of operation is to get over and it’s taken its time.

“I can’t run, I can’t jog anymore. I’m limited to certain sporting pursuits I used to be able to do. Just the simple act of going for a jog is long gone now. I’ve got a gym downstairs at home, I try and ride my bike a bit. There’s always alternatives.

“I genuinely love going for a run and that’s been taken away.”

He then says with a wry grin: “Great sport that Aussie rules.”

Brereton isn’t the only footballer of his era in the wars during retirement, but he is far from bitter. Last year he even prepared for a stint on I’m A Celebrity … Get Me Out of Here! by walking the Kokoda Trail.

“I’ve heard (Geelong coach) Chris Scott say it’s much more difficult these days and that’s his opinion, but I think that opinion is incorrect,’’ the Fox Footy commentator says.

“Given we didn’t manage our players as well in the day, given that if you were a good player you played every minute of the game, you didn’t come on back and forth, that takes an enormous toll.

“Very good sources tell me a lot of players aren’t prepared to play with any form of injury or adversity these days. The champions of today they just say, ‘no I’m not fit to play the absolute best I can’.

“We had a different thought process, if you were good enough to play a good player at 70 per cent fitness it was a better advantage for their team than a 100 per cent fit player who wasn’t quite in that category.

“I wouldn’t change it. By nature I’m fairly combative. I don’t know if it would lend itself to today’s game. The rules, how they’re looked after with in the back, the chopping of the arms, the punching in the back of the head. That would be a blessing as a forward in this day and age.”

Brereton says he didn’t suffer too many concussions. He can recall just a handful of times when he felt the effects of a head knock.

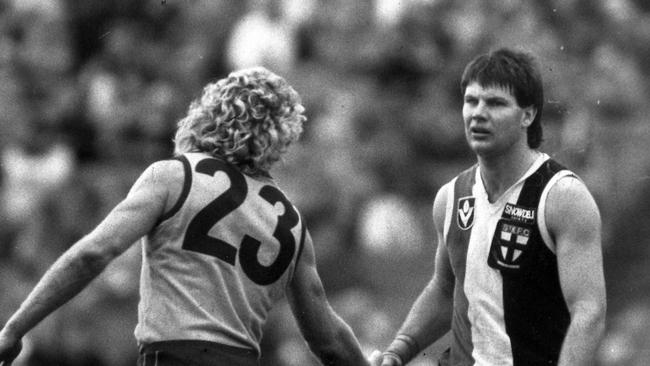

“I remember my old sparring partner Johnny Worsfold, he shirtfronted me and it was good and fair for the day, and I remember that day it was like the reverse of tunnel vision,’’ he says. “Wherever I looked it was just blurry but on the outskirts of my vision.

“I played the rest of the day kind of looking away from the ball and then trying to catch it and mark it using peripheral vision. Everything I looked deadset straight at was fuzzy and blurry so that would constitute as a concussion.

“I got accidentally clipped by a knee one day against St Kilda and that stung a little bit and when I was younger also, there was a Carlton player who threw his arm out and with the stub of his palm he broke my nose.

“There was a bit of concussion from that but nothing substantial. I’m not slurring my words or forgetting my children’s names. I feel pretty fortunate in that regard. I’ve suffered a lot of broken bones along the way, but pretty fortunate with the clarity above the shoulders.”

Brereton is concerned by the recent analysis of the late Danny Frawley’s brain, which revealed the St Kilda champion was suffering stage two chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) at the time of his death last year.

But he doesn’t want the issue to become a deterrent to future players.

“Nobody is twisting anybody’s arm to play this game,’’ Brereton says. “Nobody twists someone’s arm to become a boxer. That’s their choice. In basic form my belief is you can’t legislate to protect people from themselves. If it’s somebody’s choice and they know the pitfalls, it’s their choice.

“Everyone looks at what transpired with Danny and recognises it as an absolute tragedy and we all look at it with a great deal of sorrow, but we can’t seize up a sport just to protect people from themselves. People have to have the chance to make their choices.

“I hope it is once every 5-10 years you get one isolated case. It will happen and someone will get clocked on the head and it will be to their detriment. For every person it happens to and we sympathise with their families, other mugs who get hit in the head and, seemingly I might add, don’t suffer a great deal. There is a bit of a luck in the draw with this.”

BRERETON concedes the game has been cleaned up for the better, but the nostalgic footballer in him still misses the fire of the contest.

“My surgeon, Dr Peter Wilson, is one of my great mates. After my career at various stages when I would go and see him for a check up he would lie me face down on his bench and he’d cut bruises out of the back of my scalp,’’ he says.

“The size of garden peas from backmen who would prefer to punch you in the back of the head than the ball. I had seven cut out probably over a decade from blokes just deciding that your head is a better target than the footy. I do see the light side of that now but it was more combative back in those days.

“The game has been cleaned up for the better but I still like certain aspects of the game we played and the physical nature of it. It’s going to sound weird but it just made you feel very alive feeling in danger. Your safety and you couldn’t guarantee the safety of your opponent, it just made you a bit more sprightly. I enjoyed that aspect of the sport but it’s not like that these days.

“We used to go out there, and I tell you who was a great exponent of that type of play was Ross Lyon. If he could find someone who was vulnerable you’d cash in on it and make sure the opposition played one short.

“That was part and parcel of playing Australian rules football. That was every grade of football. If you did it untoward you got yourself a bad name and got called a dog, but that was the sport in those days.”

Brereton is frustrated by the lack of holding the ball decisions paid — “we pay two holding the ball decisions out of 100 tackles” — but he watches nine games every weekend for his commentary work with Fox Footy, including covering this year’s unprecedented finals series.

He says it’s a consuming job, and those who pass comment need to know their stuff.

One of his most emotional moments on television came last month when he was on air for the inspirational return of Majak Daw for North Melbourne. Daw nearly died from serious injuries when he fell from the Bolte Bridge in December 2018.

Putting his injuries, his career, and his achievements in perspective, is Brereton’s private pain having lost his father and brother to suicide.

“It is painful to discuss but it requires further dialogue surrounding it,’’ he says.

“It was just a magical moment for Majak to get back there. I’ve barely met him, I’ve spoken to him since, but met him a few times and I was incredibly proud of him that he’s been able to do what he’s done.

“I get asked by people, could I give an interview and to be totally honest about it I don’t, because it’s not something my family want to hear much more about, so I respect their wishes.

“And the only reason I mentioned it with Majak was because it was right there and it was just an emotional moment.”

* See Dermott Brereton commentate on Fox Footy’s finals coverage from this week on Foxtel.

Originally published as Dermott Brereton reveals horror injuries gained during career