Find out where the key players from the Essendon supplements saga are today

Coaching, careers outside football and massive pay-outs. We look at how the banned 34 Essendon players were impacted and what they have done since.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It will go down as the biggest AFL scandal of all time.

Not only were 34 players suspended for a year but countless friendships were ruined forever, jobs were lost and some people never worked in the AFL industry again.

But what happened to all the major players involved in the Essendon drugs saga?

See where these 56 people are today.

HOW THE BIGGEST SCANDAL IN AFL HISTORY ERUPTED

The biggest scandal in Australian sports history erupted at a snap press conference at AFL House at 2pm on Tuesday, February 5, 2013.

This is how all the key moments unfolded.

THE BOMBERS COME FORWARD

Essendon chairman David Evans, the softly spoken son of late AFL Commission chairman Ron Evans, fronted the cameras in the Mike Sheahan Media Centre flanked by senior coach James Hird and Bombers chief executive Ian Robson.

The club had come forward, Evans explained, to ask the AFL and Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority to investigate concerns about supplements used by its players during the 2012 season.

“The info we gathered over the last 24 or 48 hours is slightly concerning, and we want to dig a bit deeper, but we want the AFL to help us,” he said.

WHAT DID THE PLAYERS TAKE?

The scandal that would consume the game over the following weeks, months and years was the most destructive the game has known. Friendships were ripped apart, the lives of players and officials up-ended, coaches sacked and AFL and anti-doping chiefs accused of systemic leaks, manipulation of evidence and brazen breaches of the law.

In the early months, the focus was on Essendon’s shambolic injections program overseen by sports scientist Stephen Dank and the Bombers’ high-performance boss Dean “The Weapon” Robinson.

It emerged that players had been injected with vitamins and a range of exotically-named substances including the anti-obesity drug AOD-9604 and Thymosin.

Hird was accused of personally injecting “the WADA-black listed drug” hexarelin and came under pressure to stand down.

According to ASADA’s interim report club officials had also self-injected themselves with the artificial tanning drug Melanotan II.

THE “TIP OFF”

The saga turned on its head when it was revealed ASADA investigators had been told about a “tip off” phone call made by AFL boss Andrew Demetriou to Evans in the days before the club “self-reported”.

The manoeuvre would be the trigger for the AFL to conduct a joint investigation with ASADA and give the league control of and access to all confidential information.

Central to the league’s high-stakes strategy was a determination to spare Essendon players from drug bans and protect its billion-dollar commercial contracts – sheeting blame for the program to Hird and other club officials.

Essendon’s decision to “self-report” (and effectively admit to wrongdoing before an ASADA investigation had even begun) came just two days before the dramatic “blackest day in sport” press conference in Canberra where Gillard government ministers – flanked by the heads of all major sporting codes – warned of widespread drug use in Australian sport, match-fixing, and organised crime links.

But the facts would not back up the bravado in a day now widely regarded as a political stunt.

NRL club Cronulla became embroiled in the saga, which dominated the front and back pages of national newspapers.

THE WAR AND SURRENDER

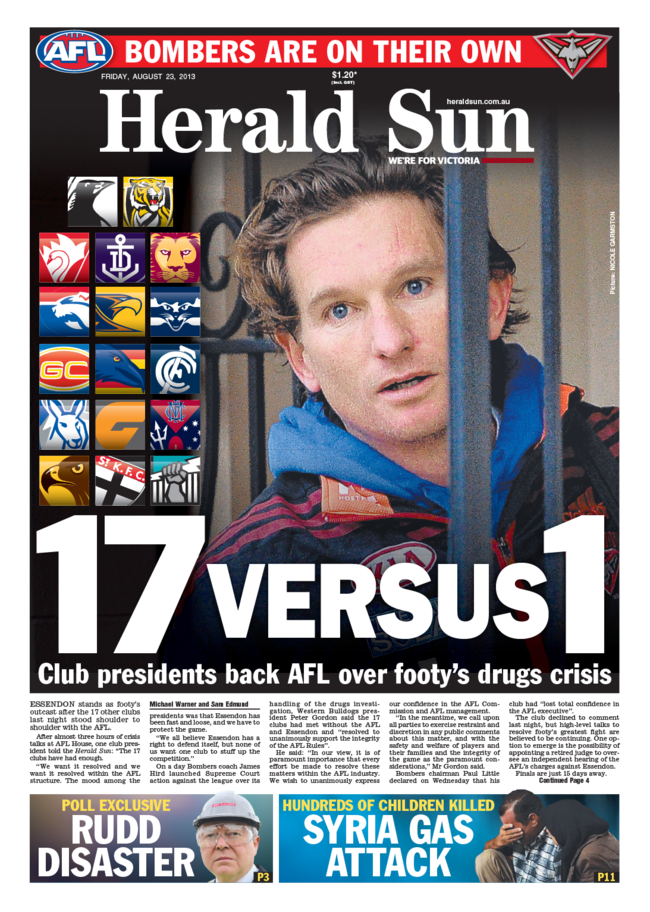

Evans resigned suddenly after the “tip off” story broke in July 2013 and all out war between Hird, Essendon and the AFL ensued with new Bombers boss, billionaire businessman Paul Little, calling on AFL chairman Mike Fitzpatrick to “step in and takeover this process, as I along with a significant percentage of the football public have lost total confidence in the AFL executive to handle this matter”.

But on August 27, 2013, Essendon yielded and was slapped with the heaviest penalties in football history: a $2 million fine, banishment from the finals and the loss of multiple draft picks for governance failings. Hird was suspended for 12 months, football manager Danny Corcoran for six months and assistant coach Mark “Bomber” Thompson fined $30,000.

Club doctor Bruce Reid refused to deal and the charges against him were dropped like a hot potato when he took his case to the Victorian Supreme Court.

It was later revealed that Hird had been showered with a series of inducements in secret negotiations between Essendon and the AFL, including “an outstanding career development opportunity”, in exchange for dropping his own court action against the league. The University of Oxford was suggested, but the coach would later settle on the prestigious INSEAD business school in Fontainebleau, France for his sins.

Demetriou sealed his own fate when he boldly declared on 3AW radio that Hird was not being paid while serving his suspension.

“That is one thing I will go to my grave on: I know 100 per cent that the AFL is not paying (Hird) and I know that Essendon is not paying.”

He was flat out wrong and resigned in March 2014, handing the reins to his long-time deputy and deal maker, Gillon McLachlan.

THE PLAYERS ARE CHARGED

Despite assurances from AFL chiefs to Bombers bosses that the players would not face doping sanctions, in June 2014, ASADA issued 34 Dons with show cause notices.

Hird and Essendon launched an unsuccessful counter attack in the Federal Court questioning the legality of the joint ASADA-AFL probe, before the players were found not guilty by the AFL Anti-Doping Tribunal after an 18-day hearing in March 2015.

Tribunal chairman David Jones declared that a three-man panel was not “comfortably satisfied” the 34 players had been administered the banned peptide Thymosin Beta-4.

But the verdict was short lived.

In January 2016, the ‘Essendon 34’ were slapped with 12-month bans by the Court of Arbitration for Sport on appeal, forcing the AFL Commission to strip skipper Jobe Watson of his 2012 Brownlow Medal.

The Dons fielded a team stacked with top-up players and duly secured the club’s first wooden spoon since 1933.

Dank received a lifetime ban, but, inexplicably, Robinson was never charged by the league or ASADA – and instead walked away with a $1 million payout after issuing Supreme Court subpoenas against Demetriou, McLachlan, Evans and Robson.

Robinson would later be cleared to work again in the NRL.

THE HUMAN TOLL

The scandal took its darkest turn a year later when Hird attempted to take his own life.

“From what I have observed over the past number of years, it seems that you can glass your partner, you can sleep with your best friend’s wife and the path to forgiveness will always be open in AFL land – but if your name is James Hird that path will be blocked,” Hird’s shattered lawyer, Steven Amendola, declared at the time.

Thompson’s life, too, spiralled into the abyss. His marriage collapsed and after police raids on his Port Melbourne apartment in 2018, he was convicted of drug possession and sentenced to a 12-month community corrections order.

As former AFL commissioner Peter Scanlon said of the devastating Essendon drugs scandal in the book The Boys’ Club: “I think they (the AFL) got caught out. They thought they could solve it in a much simpler way and underestimated the vehemence of ASADA”.

Originally published as Find out where the key players from the Essendon supplements saga are today