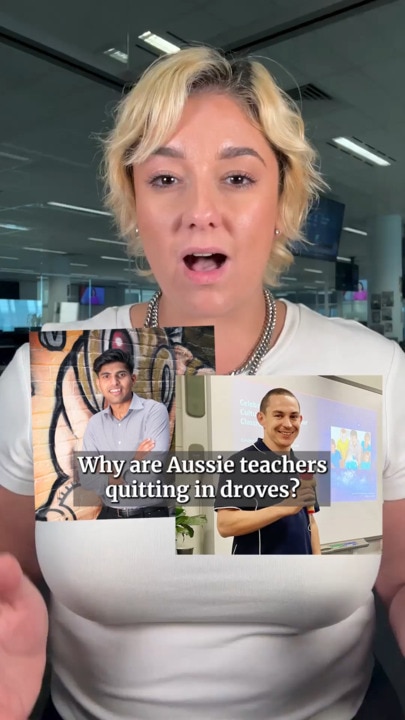

Classroom violence and the Andrew Tate effect: Two young teachers share why they quit

Joyal James wanted to be like the teachers he looked up to, instead he was thrown in with no training and faced off with students vaping in class with no fear.

Education

Don't miss out on the headlines from Education. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Students with no fear of authority, the influence of Andrew Tate and families taking no responsibility for their children are among the reasons two young teachers quit their dream jobs.

They aren’t alone, one in five graduates leave the industry within three years and the mass exodus is predicted to leave classrooms 4100 teachers short next year.

South Australian Joyal James is part of that statistic and the Northern Territory’s Darcy Fitzgerald only lasted two extra years.

Both recently left the classroom and are now sharing why in their own words.

Why I quit teaching in Adelaide’s northern suburbs

After spending less time in the classroom than he did studying the degree, Mr James started a new career this month. He tells why he walked away from teaching.

“Three in five teachers leave the profession within their first five years,” my university professor said. At the time, I thought, “that won’t be me — I love teaching. I’ll be the exception”.

I entered the classroom as a teacher in February, 2022, but three years later, I handed in my resignation.

I moved to Australia when I was eight years old, not speaking a word of English. I struggled a lot in those early years at school, learning to read and write while trying to keep up with the normal curriculum.

It was the teachers who went the extra mile so I could succeed that inspired me to pursue a teaching career.

When I began teaching at a northern suburbs school, I was thrown in at the deep end with a full timetable straight out of university.

I was teaching five subjects and looking after more than 100 students, aged 12 to 18 years.

I studied to teach business and economics but soon found myself teaching research projects and math without any extra training.

After school hours I would spend my evenings creating lessons, drafting assignments, and trying to learn content for classes outside my expertise.

Unlike other jobs I’d had with long hours, teaching drained my energy in a different way — the constant talking, interacting, and staying alert took a toll I hadn’t expected.

When I asked those around me about the workload, the response was dismissive: “the first year is difficult, it’ll get better … just work harder.”

I remember organising a meeting with the head principal to ask for advice, he ended the conversation in two minutes saying, “you’re the guy who wanted to stop teaching math, stop wasting my time”.

I felt like something was wrong with me. I’d excelled at university, yet here I was, overwhelmed and struggling to keep up.

At university, I learned the theoretical aspects of education.

I spent a semester writing 20,000 words on education – yet I never found the research useful in the classroom.

I learned what to put on tests rather than how to deal with difficult behaviour.

University does not prepare you for what the real world throws at you.

When the norm was teaching intimidating 17-year-old students with no fear of authority standing up on desks, vaping in classrooms and physically fighting each other, I had no guidance on what measures to take.

People often say, “teaching is easy; there are so many holidays”.

While the time off is nice, the intensity of the term – especially for new teachers – makes those breaks feel like a distant promise.

There’s little support to help you through those first few critical years.

You’re thrown into subjects you’ve never taught, without time to develop content or get meaningful help from colleagues who are equally swamped.

If we want to address the issue of teacher turnover, we need structures that support early-career teachers.

Workloads should be spread more evenly across the year, new teachers should have time to prepare before stepping into the classroom, and be trained for unfamiliar subjects.

Without these changes, we’ll continue to lose talented, passionate teachers who love the profession but can’t survive the system.

How Andrew Tate influenced my decision to quit teaching in the NT

Life in Territory schools was also a challenge for Darcy Fitzgerald, who has recently switched the classroom for the newsroom.

Over five years, he saw many colleagues driven out of the classroom by violence, abuse and families taking no responsibility for their children. This is his story.

On one occasion working as a secondary teacher, I called a home about a student promoting and espousing social media influencer Andrew Tate’s misogynist and widely condemned views.

I had called out the student after giving him three opportunities to retract his statement.

The parent I spoke to was at first apologetic.

However, the next day they called my line manager to complain that I had embarrassed their child and demanded an apology from me.

In that instance, my school supported me, but I have heard from many other teachers across the NT that school support has been lacking.

It is common for teachers to be physically assaulted – myself included – and to receive no apology from the families or the students.

At best, the family excused or downplayed the student’s violence, at worst they blamed the teacher themselves for being physically assaulted.

Teaching is a tough job. Students are becoming increasingly abusive and violent.

Teachers are operating in a school system that’s severely understaffed and underfunded.

Teachers are overworked, exhausted and stressed.

Through my own experiences and membership of the Australian Education Union Northern Territory branch, I heard many horror stories.

Veteran teachers with decades of experience in the classroom, were all reporting the same issues.

Student behaviour is getting worse and families are taking less responsibility for the actions of their children.

Support for the individual teacher differed from school to school.

I saw many teachers hung out to dry by schools that caved in to dogged and relentless families who were completely unaccountable for the actions of their child.

The same goes for verbal abuse.

I witnessed and received regular abuse from students.

When quizzed if they spoke that way at home, their response varied.

A quick phone call home would often reveal the reason for the abuse.

The families were either dismissive, disrespectful or on rare occasions, apologetic.

This violence and abuse is compounded by the stressful environment of an understaffed and underfunded school system.

While teaching in the NT, it seemed that no amount of money or salary increases could solve these core issues.

The recent $1 billion funding agreement campaigned for by the AEU and signed between the Territory and Federal governments will go a long way in terms of better supporting students, but it still represents the minimum amount of funding according to Gonski’s school resource standard.

NT students have the highest needs, and the funding does not reflect that.

The same can be said for the teachers’ union’s recent wage increase win.

This will see many teachers’ salaries rise by at least 16 per cent over the next three years.

However, it is still not an attractive enough amount to recruit and retain teachers.

It is too little, too late for me and many others, I’ve left the industry and am forging a new career elsewhere.