David Penberthy: Ann Marie Smith’s death should appal every Australian

Through the NDIS, taxpayers were meant to help people like Ann Marie Smith live. But a flawed system, lack of oversight, and cumbersome bureaucracy conspired to let her down, writes David Penberthy.

Rendezview

Don't miss out on the headlines from Rendezview. Followed categories will be added to My News.

How on earth did this happen?

How is it that in a civilised and affluent country like ours, where a pioneering system to protect people with disabilities has been implemented, that a person with cerebral palsy can be left at death’s door, stuck inside her suburban home immobile and alone on a wicker chair, for a full year?

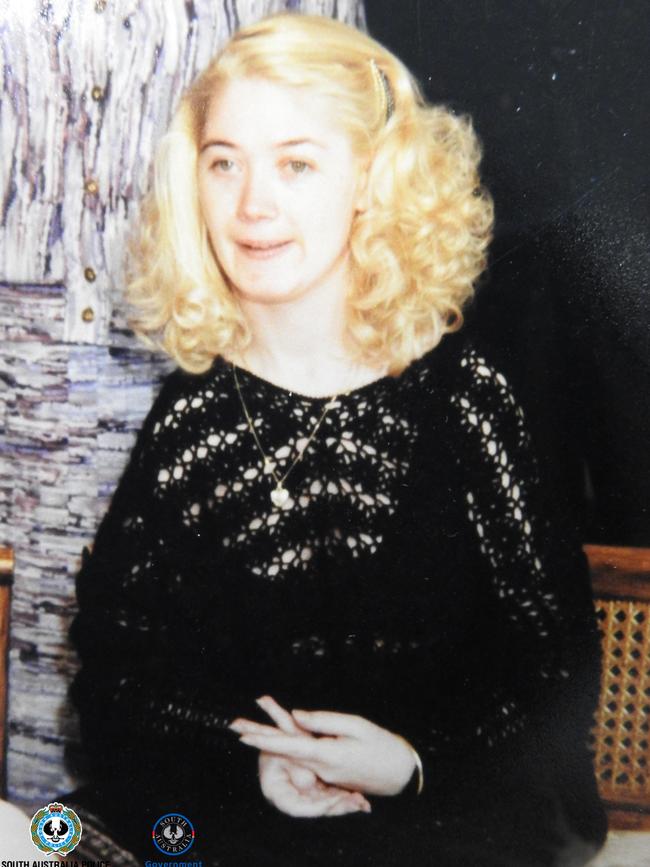

The mistreatment of people with disability now has a name in this country. That name is Ann Marie Smith.

For the final 12 months of her life, Ann Marie Smith’s only point of contact with the outside world was a female support worker who was meant to tend to her for six hours a day.

From being confined to a chair that sickeningly doubled as her toilet, Ms Smith developed septic shock, multiple organ failure from severe pressure sores and irreversible malnutrition. By the time her support worker finally called an ambulance in early April, Ms Smith was semiconscious in a catatonic state, and beyond salvation.

Ms Smith died at Royal Adelaide Hospital on April 6, aged just 54.

This case has major national repercussions with her death now the subject of a police investigation which is expected to result in charges of criminal neglect and possibly manslaughter. The South Australian Coroner is investigating, the SA Government has announced a task force, and in an extraordinary intervention, the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability said on Wednesday that even with all these other inquiries underway, it could not bite its tongue and ignore the horrific implications of Ms Smith’s death.

In a strong statement, royal commission chairman Ronald Sackville, QC, said he and his fellow commissioners “had been appalled by the circumstances surrounding the death of Ms Smith” and flagged that even with all the other inquiries underway, the commission reserved the right to conduct its own investigation.

“This deeply distressing case brings to the fore important policy questions that are already under consideration by the royal commission,” Mr Sackville said.

“People with disability have the right to live independently in the community and in the safety of their home,” he said.

There are 365,000 Australians on an National Disability Insurance Scheme plan in Australia. Alarmingly, Ann Marie Smith was one of them.

It appears Ms Smith may have become the tragic human example of what happens when two tiers of government cannot co-ordinate proper oversight, with the states and commonwealth confused as to whose job it actually was to make sure that the level of care this woman was receiving was up to scratch.

I have spent a lot of time this week talking to disability advocates and one thing everyone is confused about is the staffing arrangements that were in place by Ms Smith’s privately-owned disability services provider, Integrity Care, the company that was entrusted to “care” for her at home.

The word “care” is in inverted commas there, as it is used both loosely and wrongly. This company has been shamed by this case, and its “carer” has been sacked and is now busy talking to police.

Bizarrely, Ms Smith was afforded just this one case worker for an entire six years. The case worker was meant to see her for six hours a day. I have no idea how this worker was meant to do that seven days a week, and presumably she must have been entitled to annual leave, entitled to sick days.

One of the live questions SA Police are examining is whether the case worker was even attending Ms Smith’s home as required or was skiving off on the job, only realising how sick this poor woman had become and acting to call her an ambulance when it was all too late.

The case raises serious questions about the lack of co-ordination between state and federal authorities under the NDIS and also the fact SA, Tasmania and Western Australia do not operate a community visitor scheme for privately-run disability care providers.

Community visitors are big-hearted retirees and volunteers who after a brief training course will go and visit people in disability care to make sure they are happy and well-cared for, providing a degree of oversight separate from the disabled person’s principal carer.

SA, Tasmania and WA do not have that scheme for people in privately-run disabled care, seemingly in the expectation that the Commonwealth will keep an eye on things through the Quality and Safeguards Council.

Another remarkable feature of this case is that even though the Commonwealth was advised of Ms Smith’s death in early April, the SA Government did not find out about it until last week – almost six weeks later – when it became a police matter.

Kensington Gardens is your classic Australian eastern suburb – leafy, tree-lined streets, home to well-off Adelaideans, many of them young professionals who like the big blocks, the beautiful heritage architecture, the rose gardens.

It’s where Ms Smith sat alone in that chair, with no visitors, her parents long dead, her brother living in rural SA.

The taxpayers were meant to have come to her rescue through the creation of the NDIS, but it is obvious that the system, the lack of oversight, the cumbersome bureaucracy, and most of all an abjectly derelict carer, have all conspired to let her down.

A genuine horror show has unfolded in the middle of an emblematic part of Australian suburbia. The alarming question this case raises – and which the royal commission has been established to answer – is how many more Ann Marie Smiths are out there.

May this poor woman rest in peace.