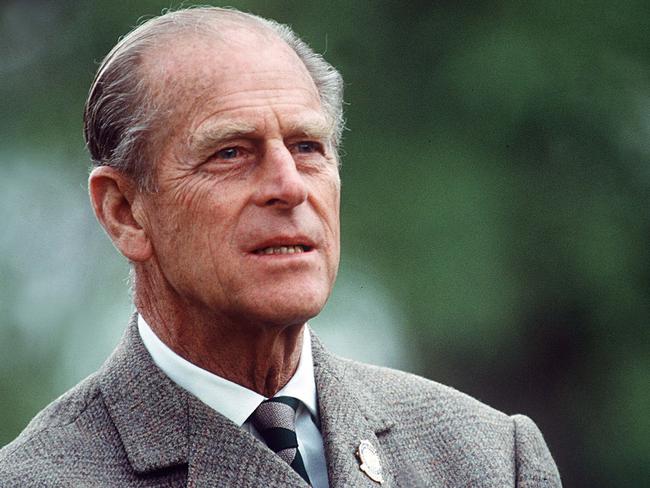

Royal historian Hugo Vickers talks about friendship with Prince Philip

A royal historian has revealed more about who Prince Philip really was and how he changed the traditional mould of a member of the firm.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

I count myself lucky to have known Prince Philip since 1996.

I was of course aware of him for many years before that and had met him formally a few times. Since the Queen and Prince Philip were loosely the same age as my parents, to me there was something parental about them, though I remember thinking how lucky I was that he was not in fact my father.

Before getting to know him and understanding him, I hate to say he reminded me somewhat of a rather overly sporty schoolmaster that I spent some time avoiding. I thought of him as stern and forbidding.

This was in the 1960s when Prince Charles followed his father about, copying his hands-behind-the-back stance, though rather uncomfortably.

Later I read Cecil Beaton’s accounts of photographing the royal babies. When he photographed Prince Andrew in 1960, Beaton noted how overawed Prince Charles seemed to be, “as if awaiting a clout from behind, or for his father to tweak his ear of pull the tuft of his hair at the crown of his head”.

I was told that the Queen Mother once said of her son-in-law: “He can be quite nice sometimes.”

I suppose I first talked to him at an engagement in 1988, when he asked me what had inspired me to write about Vivien Leigh. I replied: “I thought I could do better than the previous biographers.”

To this he replied: “Really.”

And I half expected him to continue with a bark: “You little whippersnapper, what on earth gave you that conceited idea?”

Prince Philip liked an argument and he accepted nothing at face value. He also liked to take the contrary view.

A courtier was driving with him on the private estate at Sandringham, when Prince Philip noticed some trippers, and commented: “They’ve no right to be there.”

A few minutes further on, the courtier noticed some more trippers and said: “Look, Sir, some more. How awful!”

“What do you mean? They’ve every right to be there!” snapped Prince Philip, totally contradicting himself.

It is hard to assess how he is thought of in the world. He did not inspire the same affection as the Queen, but then he never sought it. He came to be admired and respected for fulfilling his role in supporting the Queen, and doing his bit to the full.

Neither the Queen nor he wasted any time wondering what people thought of them – they just got on with the job, and this served them well. In the press he had the tedious reputation for making “gaffes”.

All he was doing was trying to engage with people as quickly as possible. This could be offensive, if you did not understand what he was up to. Luckily I had read that what he hated most in life were conceited chairmen who swanned into a public engagement, made a slick speech, and frankly did not know what they were talking about. He liked to chide such figures.

He did it to me when I was running the Jubilee Walkway Trust in London. We created a special walking route around London, called the Jubilee Greenway, which linked up the Olympic sites and celebrated the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee.

Appropriately, it was 60 kilometres long and marked by special disks in the pavement along the way. (We have since introduced a Commonwealth Walkway in the Gold Coast in Australia – opened by Prince Charles in 2018, and another in Perth.)

As Chairman, I made a short speech outside Buckingham Palace before the Queen unveiled the first disk in the middle of the Palace gates. Prince Philip attacked the disk on all counts – the horses would shy when they rode over it – “I’m telling you they will!” – it should have been round instead of square – on he went. Then on leaving, mindful that the route was 60 kilometres long, he asked: “So – are you going to walk it then?” I said: “I have walked every inch of it,” at which point a huge grin crossed his face. He was satisfied.

In contrast to his public outings, there can be few men easier to talk to one-to-one in his office. I was taken up to see him by his Private Secretary, Sir Brian McGrath, when working on my biography of his mother. It is never easy to talk to anyone about their mother, least of all him. So I decided to ask him about other figures in the story – his grandmother, key influences and so on.

Thus we circled his mother until he volunteered his views on her. I was interested in the logicality of his mind. I said I was not sure when or even if she had ever visited Jerusalem, where she is now buried – in the Russian Convent on the Mount of Olives. Immediately he said that when she announced her intention of being buried there, they had said it would be hard for them to visit her. She countered with the line: “Nonsense, there’s a perfectly good bus service!”

His point being that she must have gone there to know that. When I came down, Sir Brian asked me how it had gone, and then commented: “Well, you were with him for an hour. If it hadn’t gone well, you’d have been out in 10 minutes!”

When I finished the book, Prince Philip read it in typescript. He loved to write: “Rot – rubbish – nonsense” in the margin, which did not always mean he was right; I could fight my corner. When he wrote: “Is this necessary?” he did not dispute the truth, but he found it uncomfortable. Interestingly in the years since my book came out, he never mentioned it to me (nor I to him), but he told other people that he learnt more about his mother from it than he had known in her lifetime.

The second talk was about St George’s Chapel. On that occasion he was so forthcoming about Canons “borrowing” money from the College of St George, and how they had had to get rid of a particular warden, that most of the conversation did not find its way into the book.

I was also lucky to sit next to him twice after dinner, occasions when he was in a completely receptive mood, and you could say anything to him.

He laughed when I told him that what I most enjoyed at the annual St George’s House lecture was watching him making occasional notes as the Speaker talked, and then summing up what we had been told.

On such occasions he did not hold back. I once heard him accept a number of points and then say, “As far as I can see, the rest is all jam!”

And after a dinner at Highclere (the estate used in Downton Abbey), I found myself telling him the story of Rosemarie Kanzler, a Swiss manicurist who amassed a huge fortune by advantageous marriages, some of which ended in divorce and at other times in widowhood when her “sorrow” was mitigated by the transfer of considerable chunks of real estate. He laughed a lot as the story unfolded, but then under his breath at the end, he muttered “pointless” and I thought, yes, that’s it. To him such a life of amassing riches and houses would be pointless, since his whole life had been one of service.

I have often been struck by the conciliatory line he produced on Anglo-German relations in 1962: “It may be difficult for people to see any virtue in forgiving one’s enemies, but let them reflect that it is much more likely to achieve a better future than stoking the fires of hatred and suspicion.”

Prince Philip was one of the last of a generation that served right through World War II. The much-wanted boy in a family of four older sisters (the eldest born some 16 years before him), he was the son of Prince Andrew of Greece, and his wife, Princess Alice of Battenberg. He was born in Corfu in June 1921.

His father, an officer in the Greek Army and something of a boulevardier, was almost executed by the Greeks, and the family left Greece for more or less permanent exile in 1922. His mother, a great-grand-daughter of Queen Victoria, was a more serious figure, more or less completely deaf and deeply involved in religion. Royalty are never happy in exile, and Prince and Princess Andrew found themselves living at St Cloud, to the west of Paris, relying on the bounty of generous relations, in particular Princess George of Greece, whose fortune came from the casino in Monte Carlo.

In 1928 Prince Philip’s parents marked their Silver Wedding and soon after that Princess Alice suffered a serious religious crisis nervous breakdown. Prince Philip told me: “My mother was ill, my father was away. I had to get on with it.”

This proved his philosophy throughout his long life. An outgoing character, he thrived at Gordonstoun. He served gallantly in the British Navy, first in Mediterranean home waters, and later in the Far East.

He was mentioned in dispatches for his service at Cape Matapan. He continued his naval career until 1952, when it was brought to a sudden end by the death of King George VI. Thereafter his primary role was to support the Queen, which he did in stalwart fashion in a marriage that lasted over 70 years. Living into his late 90s, it was generous of the Queen to allow him to officially retire in 2017, after which (and of course before which too) his great passion was carriage driving. This he did with great determination.

In those last years, when feeling well, he would walk to the Royal Mews, but if a little under the weather, he would be driven down by car. His last major public appearance was at Prince Harry’s wedding in May 2018, when he strode gamely into St George’s Chapel, only weeks after a hip replacement operation.

I suspect that only when Prince Philip’s extensive archives are explored will we fully understand the scope and range of his many achievements. And of course, unlike Queen Victoria (widowed at the age of 42), the Queen was lucky to have him for so long.

More Coverage

Originally published as Royal historian Hugo Vickers talks about friendship with Prince Philip