‘Never supposed to rule’: Twist of fate that turned ‘geeky’ doctor into a ruthless dictator

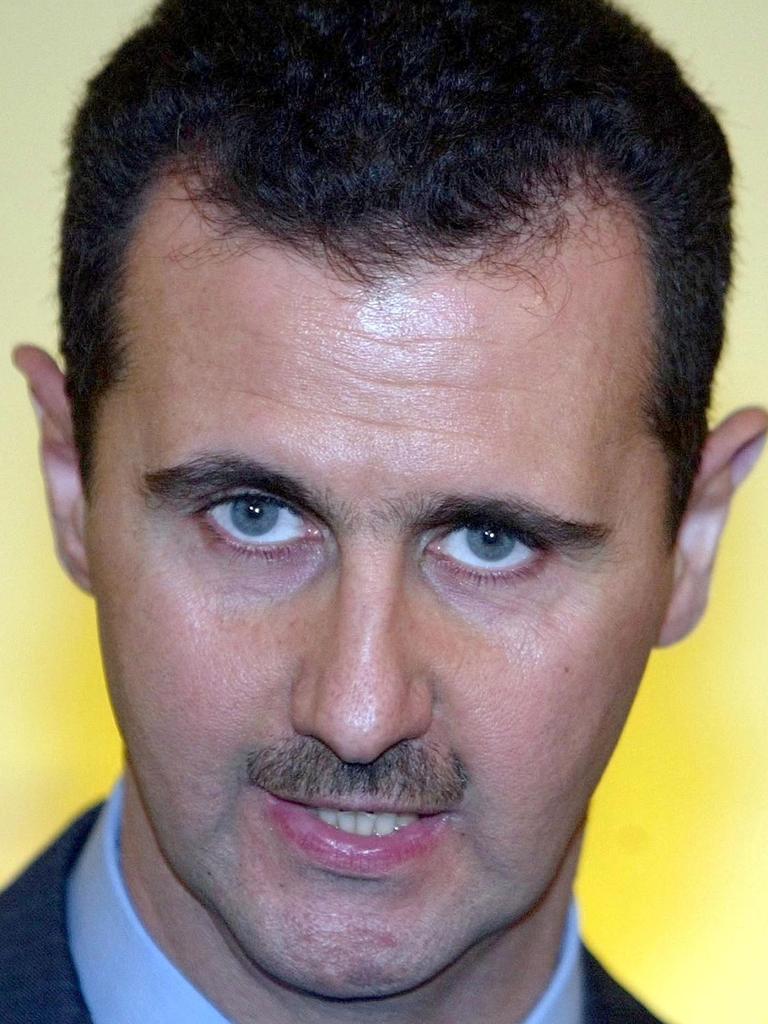

One shocking twist of fate saw a “geeky, lanky” eye doctor transform into a bloody tyrant responsible for the deaths of half a million people.

Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad acted with impunity. He “disappeared” tens of thousands of people. Many more were tortured, raped or detained. And fully 90 per cent of his subjects lived below the poverty line.

Now, the despot has fled to the dubious sanctuary offered by Russia’s President Vladimir Putin.

And the world is taking stock of the damage done to the once proud Middle Eastern power after 54 years of his family’s rule.

“The dictator’s demise will be cause for celebration, though it will open up new dangers for the region,” says Center for Strategic and International Studies analyst Professor Daniel Byman.

It took just 12 dramatic days for the self-styled president’s hollow regime to collapse upon itself. But it took 24 years of brutal repression, corruption, desperate deals and fraud to reach that tipping point.

Assad and his wife, Asma, abandoned the country on Sunday evening local time.

His latest opponent – Abu Mohammed al-Jolani – was racing unopposed down the long highway from the city of Homs in Syria’s north to the capital, Damascus, in the south.

Assad’s elite and privileged special forces troops melted away into the desert ahead of the advancing rebel forces.

And his long-suffering subjects surged into the streets in the regime’s heartland – venting their frustration at decades of fear and repression.

Assad’s statues and billboards were toppled and defaced in Tartus, Latakia and the sprawling suburbs of Damascus. Regime offices have been looted. Political prisoners set free.

With the fate of the 23 million-strong nation now up in the air, the world is reflecting on how it came to this. And what it took to finally bring down the Assad dynasty’s murderous reign.

“In truth, the international community has misjudged the situation in Syria in recent years,” says Middle East Institute Syria expert Charles Lister.

“While lines drawn on maps and the stagnation of diplomacy led to assumptions that Assad was here to stay and was consolidating his rule, the regime had, in fact, been decaying and fragmenting from within.”

Hollow man

Bashar al-Assad was an autocrat who attempted to suppress every challenge to his rule and corral Syria into a land of stability amid a tumultuous region.

But Bashar was never supposed to rule.

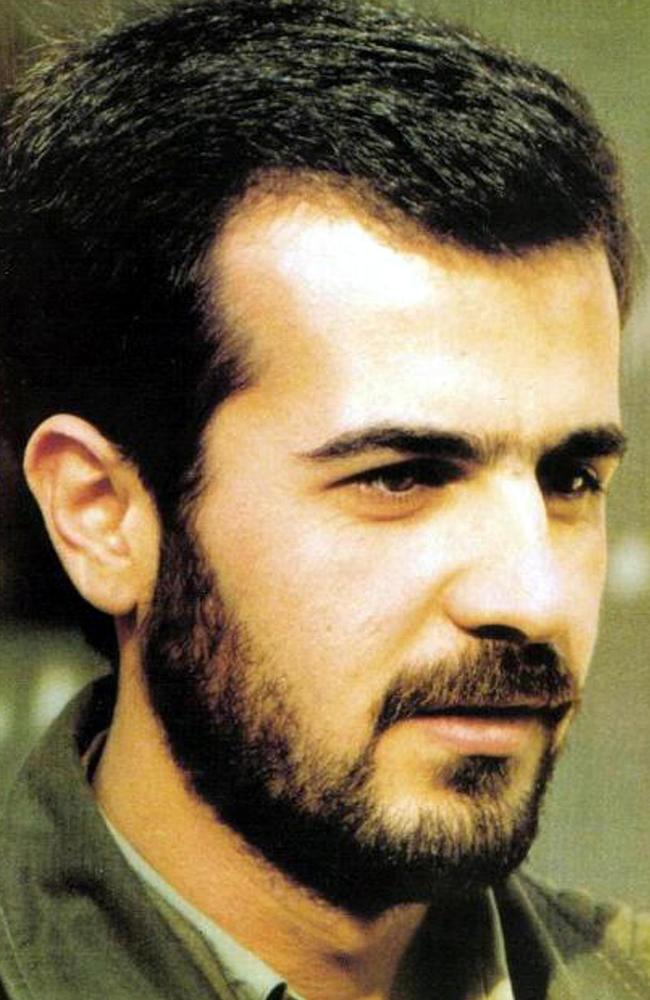

That role had been reserved for his handsome and dashing eldest brother, Basil (sometimes referred to as Bassel).

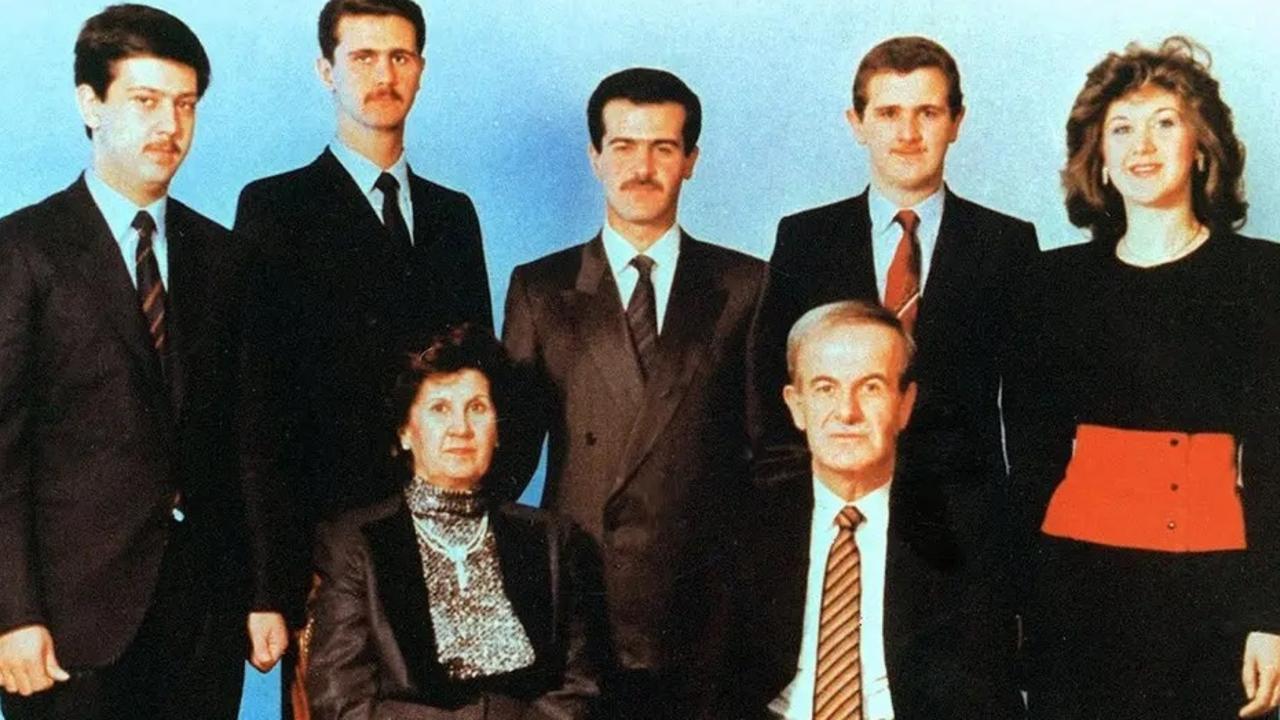

Hafez Al-Assad established the family dynasty in 1970. The air force officer seized power in a coup and brutally established control through a personally controlled secret police.

Fate intervened in 1994 when his carefully groomed heir-apparent was killed in a car crash.

The tall, lanky, “geeky” Bashar had been in London. He was training to be an eye doctor.

Suddenly, he was heir to the regime.

Bashar was rushed through officer training and appointed to the rank of colonel. His task was to demonstrate his martial prowess. To be a “strong man” like his father.

But, after a 30-year reign, 69-year-old Hafez died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 2000.

And Bashar, 34, was six years too young under the constitution to assume the role of president.

An urgent session of parliament was called to fix that inconvenience. And Bashar unsurprisingly won the following national vote in which his name was the only one to appear on the ballot paper.

Initially, the world reacted with hope.

Bashar appeared utterly unlike his father. He was quiet, almost introverted. His manner was gentle. His new wife, Asma al-Akhras, was a stylishly modern British-born woman.

He had his father’s political prisoners freed. And the ruler insisted on living in a (relatively) humble apartment instead of the presidential palace.

Bashar even began to encourage an atmosphere of debate and openness.

It barely lasted a year.

In 2001, Syrian community leaders signed a petition calling for the establishment of a multi-party democracy. In anticipation, some even formed their own political parties.

Bashar responded by unleashing his secret police.

And he had his younger brother, Maher, take control of the Presidential Guard.

Model of a modern major general

With his political dominance firmly enforced, Bashar turned his attention to the national economy.

He eased import and export regulations. He allowed in foreign investors and banks. He encouraged a new spirit of private-sector entrepreneurship.

He also urged a new era of religious tolerance.

Bashar’s family heritage was with the Alawite sect – a branch of the Shiite Islamist movement.

His secular rhetoric initially reassured Syria’s many minority groups. Antioch Christians, the ancient Druze monotheistic group and the Sunni Islamists – which make up two-thirds of Syria’s population – felt safe from Shiite repression.

At first, it worked.

Modern shopping malls were built. Restaurants were opened. Tourism surged.

The Assads adopted the lifestyle of a glamour couple.

Gushing media proclaimed Asma al-Assad the “most stylish woman in world politics”. But for Syrians, her previously celebrated refined taste quickly became equated with French Queen Marie Antoinette’s “let them eat cake” fame.

Bashar’s cousin Rami Makhlouf quickly established Syria’s biggest business empire. It survived until the two had a major falling out.

The thaw in tribal and religious tensions saw commerce and industry expand. But international relations remained a sticking point.

Bashar had inherited his father’s hatred for Israel.

He wanted the Golan Heights returned to Syrian rule. And he kept his father’s troops inside Lebanon to maintain control and confront Israel there.

Lebanon’s Prime Minister Rafik Hariri wanted Syria out. But his subsequent assassination backfired, forcing Bashar to withdraw in 2005.

Meanwhile, two international wars in Iraq had caused a dynamic shift in Middle Eastern politics.

Sunni Islam countries such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia took sides with the United States.

Shiite Islam communities – such as Hezbollah, the Houthis and some Palestinian militants – were rallying to Iran’s flag.

Keeping his Shiite power base happy caused Bashar to adopt a pro-Iran position. And that unsettled the Sunnis.

Unlikely survivor

“Bashar, more fallible, enigmatic, and perplexing than his father, is clearly not cast in the traditional mould of an Arab leader,” wrote Middle East analyst Patrick Seale in 2012.

“He has managed to survive the uprising, but it seems unlikely that he will equal his father’s record.”

The 2011 Arab Spring swept like wildfire across the Middle East.

Bashar, however, felt confident.

He was convinced he had turned Syria into an autocratic utopia.

He had quashed all political opposition. But he had also opened up the national economy and established security for all his population.

Egypt’s regime may have fallen. But his Syria was different.

Bashar was wrong.

Syrians took to the streets in peaceful protest to demand new freedoms and democratic elections.

In reply, Bashad ordered his security forces to enforce a violent crackdown.

Assad denied he was quashing a popular revolt.

Instead, he blamed “foreign-backed terrorists” for undermining his regime.

Syria soon fractured along religious and ethnic lines.

“Both Hafez and Bashar had been slow to recognise and address the groundswell of complaint against rising poverty, corruption, and government neglect that would fuel the uprisings,” Seale wrote.

“Preoccupied with foreign affairs, they failed to pay sufficient attention to the domestic scene, often turning a blind eye to the abuses and profiteering of their close associates, including members of their own family.”

Civil war erupted.

And Bashar was willing to resort to the use of indiscriminate chemical weapons to guarantee victory over troublesome pockets of resistance. Some 500,000 Syrians lost their lives. And millions of civilians – uncaring about religious or political dogma – fled for their lives into neighbouring Jordan, Turkey, Iraq and Lebanon.

But Bashar could not win alone.

It was only through considerable help from Russia and Iran – both militarily and financially – that Assad maintained control over Syria’s major capitals. But he never really regained control over much of the countryside.

Moscow and Tehran also demanded a hefty price.

Putin demanded control of naval and air force bases on Syria’s Mediterranean coast in exchange for the presence of advanced combat jets. Iran and Hezbollah provided military advisers, troops and weapons – in exchange for the use of Syrian territory for attacks on Israel.

Bashar spun this as victory.

“For years, the international community had written off any chance that Syrians’ demand for change would ever be realised, embracing instead the concept of a ‘frozen conflict’ and gradually withdrawing attention and resources away from Syria policy,” says Lister.

“In 2023, most of the Arab world reembraced Assad, rewarding him with his seat back in the Arab League and granting him and his regime with high-profile public visits across the region.”

House of cards

Bashar al-Assad’s regime withstood more than a decade of revolts, civil war and international sanctions. But, in the end, it took just 12 days to collapse.

His long-feared security forces and elite troops ran away.

For some, though, it was not unexpected.

“By silencing dissidents and solidifying his territorial grip on Syria, Assad seeks to convey the impression that Syria is going back to its pre-2011 status quo,” Chatham House Middle East expert Lina Khatib wrote in 2020.

“But his regime is built on the illusion of a state, and what little power it has rests in the hands of its puppet masters. Assad’s endgame in Syria leaves him sitting on a fragile throne of a thousand precariously balanced pieces.”

In the end, President Putin was unable to rescue the Assad dynasty. Russian forces have been decimated in his bungled invasion of Ukraine.

Iran is in little better state. Its militant proxies of Hamas and Hezbollah have been devastated, and their leaderships decimated.

Ultimately, Bashar was left only with the “loyalists” he had rewarded with positions of power.

“Profiteers infected Assad’s security apparatus at all levels,” Khatib wrote.

“In some cases, militias have transformed into armed gangs that intimidate civilians in loyalist areas.”

Eventually, even Bashar’s hometown of Qardaha was controlled by a criminal gang.

“Even the Syrian army and security institutions have become transactional, with local branches of the security services pursuing their own interests rather than those of the state.”

Now, Bashar has fled.

And he’s left behind a nation starkly divided along religious, political and economic lines.

“This sudden turn of events … has left regional powers scrambling to assess the fallout and its broader implications,” says Deakin University researcher Ali Mamouri.

“The stark divisions among these groups, combined with the absence of a mutually acceptable mediator, suggest that Syria may now face prolonged instability and conflict.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @jamieseidel.bsky.social

Originally published as ‘Never supposed to rule’: Twist of fate that turned ‘geeky’ doctor into a ruthless dictator