St Vincent Institute research finds Alzheimer’s disease treatment requires combination of therapies

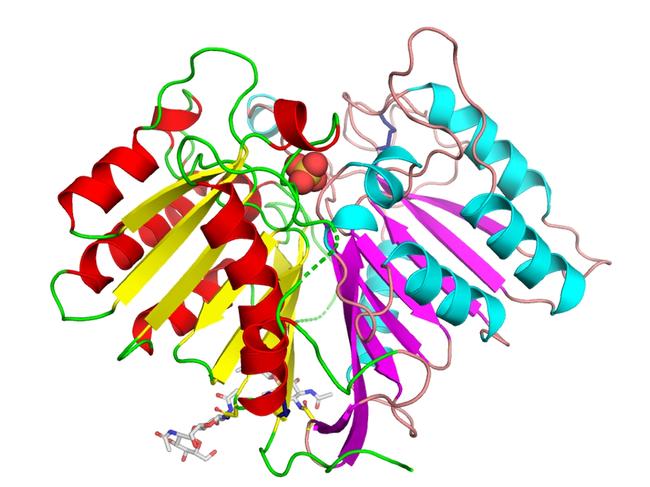

A team from St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research has revealed for the first time the precise three-dimensional structure of PLD3 – an enzyme associated with Alzheimer’s.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Melbourne researchers have cracked the code for an enzyme found in high levels in the brain that could be key to treating Alzheimer’s.

The team from St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research has revealed for the first time the precise three-dimensional structure of PLD3 – an enzyme associated with Alzheimer’s.

Professor Michael Parker is head of SVI’s structural biology lab and is leading research performed by Japanese Masters student Kenta Ishii and Greek PhD student Marialena Georgopoulou with lab members.

“We desperately need drugs, we probably need a drug combination to be most effective, and any discovery of new targets that potentially could lead to drugs is important and exciting,” he said.

“Our PLD3 discovery is a first step in developing novel drugs that could be given orally in combination with drugs being developed against other targets. The cellular location of PLD3 suggests it could be a target for other dementias like Lewy body dementia.”

He said the team had used the discovery to understand how genetic mutations associated with Alzheimer’s affect the structure and function of PLD3.

Professor Parker said Alzheimer’s was the most common form of dementia and the most heavily researched.

Other types include Parkinson’s disease and the lesser known Lewy body dementia.

“One of the big puzzles with Alzheimer’s is what causes the disease,” Professor Parker said.

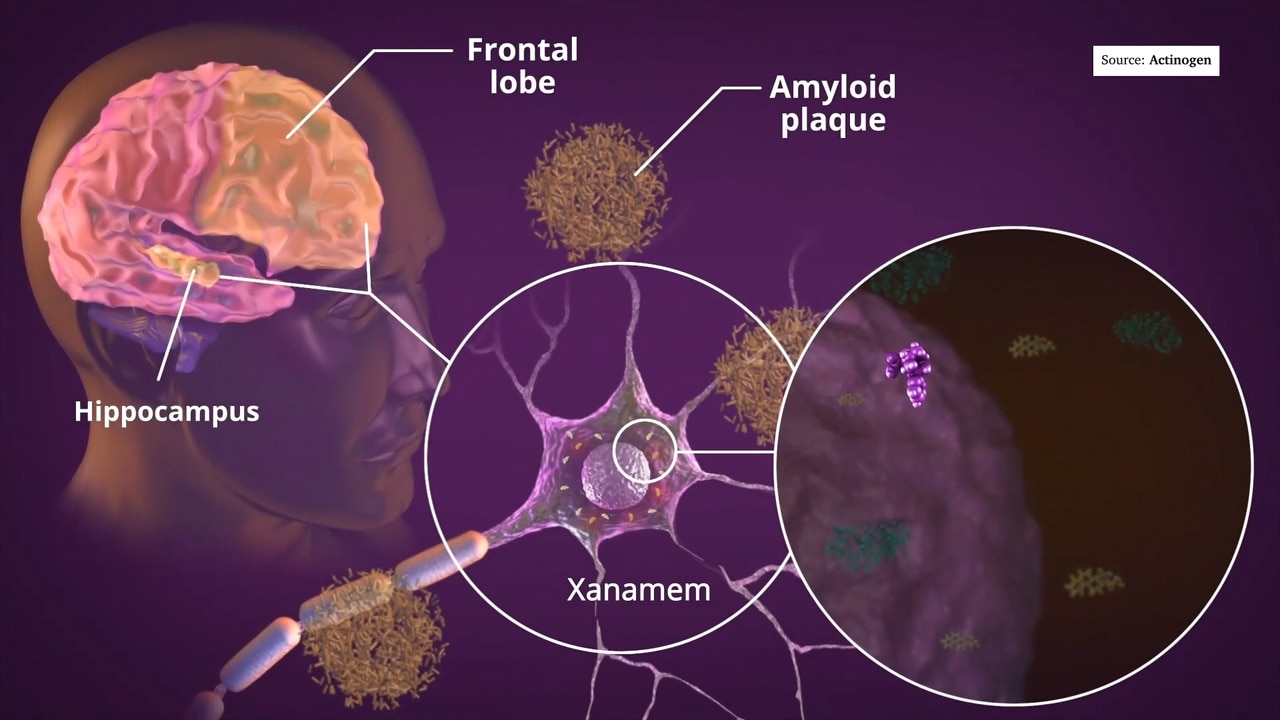

“There has been a longstanding hypothesis that a toxic protein called amyloid beta is responsible. This is the protein that constitutes most of the amyloid plaque seen in the Alzheimer’s brain.

“PLD3 is known to control levels of amyloid beta in the brain and excess levels can be disposed of by a special cell called the microglia. These are the immune cells of the brain and they chomp up toxins like amyloid beta. They can also engulf and destroy invaders such as bacteria and viruses.

“Then the question is, why is amyloid beta made in the first place if it is toxic? There is evidence that amyloid beta can also disable bacteria and viruses and so are another line of defence, together with microglia, against brain infections.”

He said if the microglia get overwhelmed by too many toxins or invaders, they can release inflammatory molecules that can lead to the death of brain cells and cognitive decline seen in the disease.

The research was published in the FEBS Journal and means the team can now search for molecules to make the enzyme work better to lower the production of the amyloid beta.

“We are in a great position,” Professor Parker said.

“The job for us now is to convert the molecules we’re finding into really good drug-like molecules that get into the brain.”

Originally published as St Vincent Institute research finds Alzheimer’s disease treatment requires combination of therapies