Journalists who uncovered Lawyer X scandal reveal how proposed new laws could lead to cover ups

Proposed new laws to protect police informers could serve to undermine the justice system and cover up abuses of secret power, like we saw in the Lawyer X scandal.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Victoria Police never wanted the Lawyer X scandal to be told.

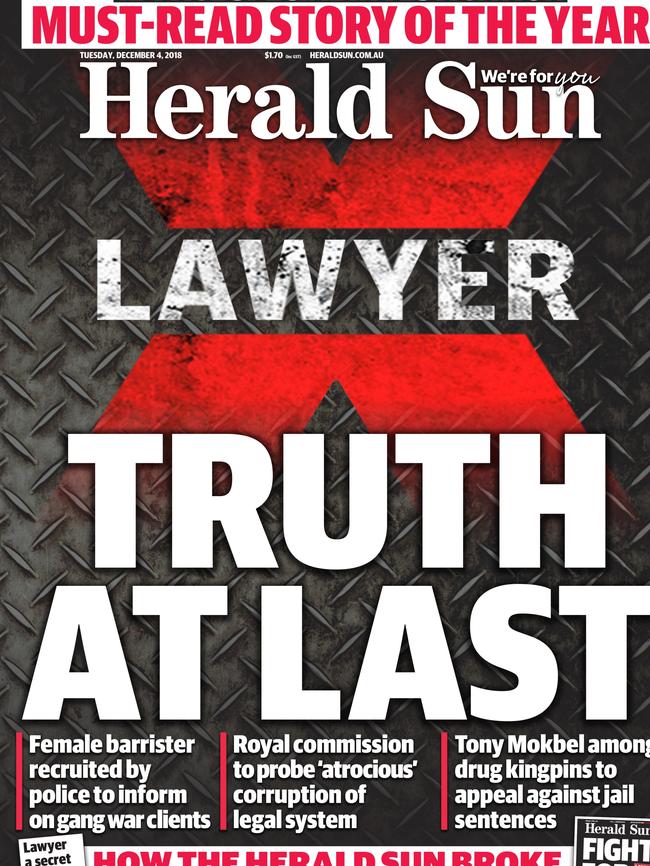

When the Herald Sun first published the story, in 2014, the police rushed to court to try to stop the presses. As it did again. And again.

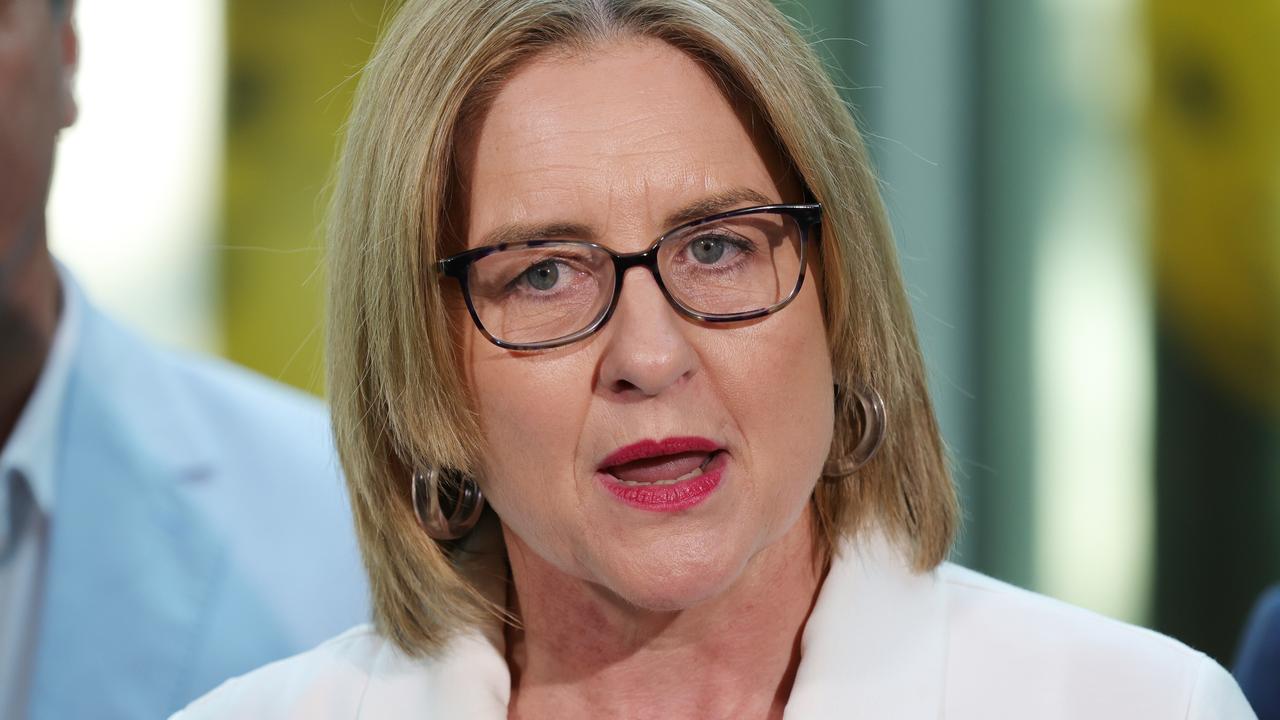

High profile criminal lawyer Nicola Gobbo’s underhanded collusion with police had possibly helped to jail gangland heavyweights such as Carl Williams and Tony Mokbel. The Herald Sun believed that the public had a right to know, and so returned to court to challenge Victoria Police’s recalcitrance on dozens of occasions.

A secret Supreme Court trial, its appeal case, and, ultimately, a royal commission, came to the same conclusions.

So did the High Court of Australia, which described the relationship between Gobbo and dozens of police officers as “reprehensible conduct”, in a decision which placed the need for truth ahead of Gobbo’s need to remain anonymous.

Underpinning the past nine years of revelation has been a simple motivation. It explains the Gobbo books and podcasts and documentaries and surges of interest, from LA to London, about the rather peculiar tale from the other side of the world.

The motivation is this: that the wholesale defrauding of the justice system, by defence barrister Nicola Gobbo in her alliance with Victoria Police, could never be allowed to happen again.

As the royal commission’s Margaret McMurdo put it, she had to ensure that “individual and institutional shortcomings … are not repeated”.

This self-evident truth explains the confusion and headshaking expressed by many learned observers in recent days.

The Andrews Government will this week push legislation, ostensibly based on some of the 111 recommendations of the royal commission, aimed at increasing public confidence in the justice system.

Yet aspects of the proposed laws have instead instilled doubt, amid fears that the laws could enshrine corruption rather than expose it, and that they remove an accused person’s fundamental right to silence.

The legislation appears to give police the authority to register those with privileged information, such as lawyers, journalists, doctors, priests and politicians, as so-called human sources.

It appears to offer police a licence to once again use a lawyer to snitch against their own clients. The argument that such provisions will engender trust in clients who need to confide in a lawyer seems fraught.

Victorian Bar president Sam Hay KC said: “The registration of lawyers as informants will lead to precisely the same conduct that gave rise to the Royal Commission in the first place.

The roles of informant and lawyer are fundamentally opposed. One person cannot ethically wear both hats at the same time.”

Law Institute of Victoria president Tania Wolff rejected the notion that lawyers could ever covertly inform against their clients. She argued that the legislation, in its current form, could legitimise unethical behaviour.

“The duty of strict confidentiality is there to protect the client,” she said.

“Encroaching on this undermines community trust and confidence in the administration of justice. Lawyers play a central role in the administration of justice and that does not include being an evidence gathering instrument of Victoria Police.”

Further, the laws would criminalise the revealing of a human source’s identity. In theory, a journalist could be prosecuted and jailed for the pursuit and publication of a story such as the Lawyer X scandal.

Former Herald Sun editor Damon Johnston led the “long and lonely” fight to reveal the Gobbo story from 2014. He sensibly chose not to name Gobbo at the time.

“On face value, these new laws are alarming,” he said.

“That they could impede the ability of a journalist to expose the next Lawyer X is something that the public needs to be concerned about.

“They seem to be the exact opposite of the spirit of the royal commission findings.”

Shadow Attorney-General Michael O’Brien agreed: “If this law had been in place at the time of the Lawyer X scandal, we never would have found out the truth. The Herald Sun would have been gagged and Victorians kept in the dark about one of the biggest legal scandals in our state’s history.”

By 2014, Victoria Police had for several years been critically analysing its use of a barrister who snitched on her clients.

A 2012 internal report by former chief commissioner Neil Comrie had been scathing of Gobbo’s use, but had led to almost no external oversight of the scandal.

The Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission, the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, and the Commonwealth DPP’s office had been drip-fed snippets of the greater scandal.

Indeed, warnings about Gobbo’s unconscionable choices dated as early as 2006 when Carl Williams, in a prison cell and facing convictions for four murders, wrote to the DPP and the Law Institute to accuse Gobbo, rightly, of unethical conflicts and double dealing.

As the royal commission many years later attested, nothing much eventuated from these highly secret inquiries.

Nothing much happened until the Herald Sun began publishing the details of the dirty secret that courtroom judges had been misled in an elaborate operation spearheaded by the police force’s very secretive Source Development Unit.

Questions of safety for informers, who are generally motivated by self-preservation, reward or an avoidance of jail term, are wrestled with by police departments and security agencies worldwide.

The difference here, of course, is that no other agency is thought to have engaged a lawyer to systemically snitch against their own clients, leading to the question of whether dozens if not hundreds of convictions ought to be overturned.

The unsolved story of the murders of Terry Hodson and his wife Christine in 2004, after the former’s police informer status became common knowledge in criminal circles, underscores the need for robust controls.

The sad tale raises many conundrums, as applied by the proposed laws, given that the investigation into Hodson deaths was skewered by the priority of keeping Gobbo’s informer status a secret (which also impeded scrutiny of questionable police practices, such as green-lighting Terry Hodson to sell huge amounts of illicit drugs).

Under the new laws, would it be an offence to report that Hodson the informer was possibly murdered because he was an informer?

Victoria Police’s approach to the royal commission was less than forthcoming, a kind of cultural amnesia the public also witnessed in hotel quarantine hearings, when no one from Premier Dan Andrews down claimed to know who was responsible for a Covid policy that directly led to 800-odd deaths.

The police fought to withhold secrets, including its steadfast refusal to divulge the names of 11 secret informers requested by the commission.

Some police members said they could not remember; some refused to recognise the ethical morass of using a lawyer to snitch on her clients, notwithstanding that such a brazen choice has already seen two men – Faruk Orman and Zlate Cvetanovski - have their convictions overturned, while others, such as Tony Mokbel, clamour for prison release.

The Office of the Special Investigator was set up, as recommended by the royal commission, to examine whether police officers perverted the course of justice in their use of Gobbo.

Yet after 12 months, retired High Court judge Geoff Nettle reported little progress, citing contested access to crucial documents held by agencies such as Victoria Police.

The proposed laws appear to arm Victoria Police with informer protections, certainly, but to also cover up egregious abuses of secret power. Just as the force tried to bury the Lawyer X scandal.

As Johnston has said: “This wasn’t corruption with cash in brown paper bags as it was in Queensland. Potentially ... this was corruption at a far grander scale, at a systemic scale, and a far more damaging scale.”

And the public had the right to know.

Originally published as Journalists who uncovered Lawyer X scandal reveal how proposed new laws could lead to cover ups