Valerie Taylor on the highs and lows of an adventurous life

She survived polio to become a doyen of marine cinematography and conservation. Now aged 84, Valerie Taylor’s adventures continue ...

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Read more great stories like this in Independent Lifestyle magazine, in your Sunday Mail on February 23

- Pedal to the metal: Mountain biking for the over-50s

- Meet SA’s ghost hunters as they get into the spirit

- Subscribe now for our best offer: Just $1 for the first 28 days

Valerie Taylor isn’t afraid of much in life. “I don’t like whirlpools – I got in one once but I wasn’t even afraid then, I just thought I was going to die, but we’ve all got to die some time,” says Taylor, 84.

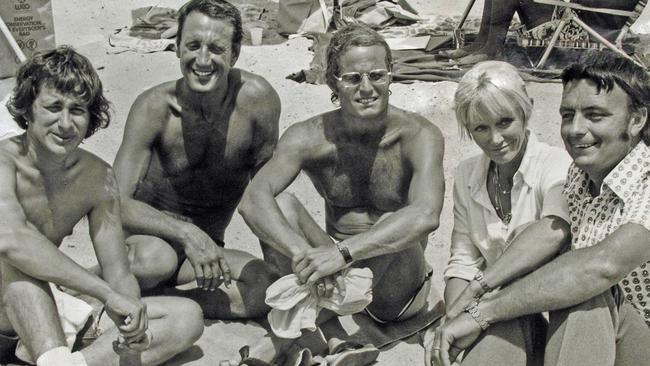

The attribute came in handy working with husband Ron on Hollywood classics, like Jaws, and marine documentaries, many of which required diving with sharks to get the necessary footage.

The Australian adventurers were responsible for opening many eyes to the wonders of the deep and campaigning for marine conservation amid their filmmaking exploits. Valerie became a member of the Order of Australia in 2010, seven years after Ron.

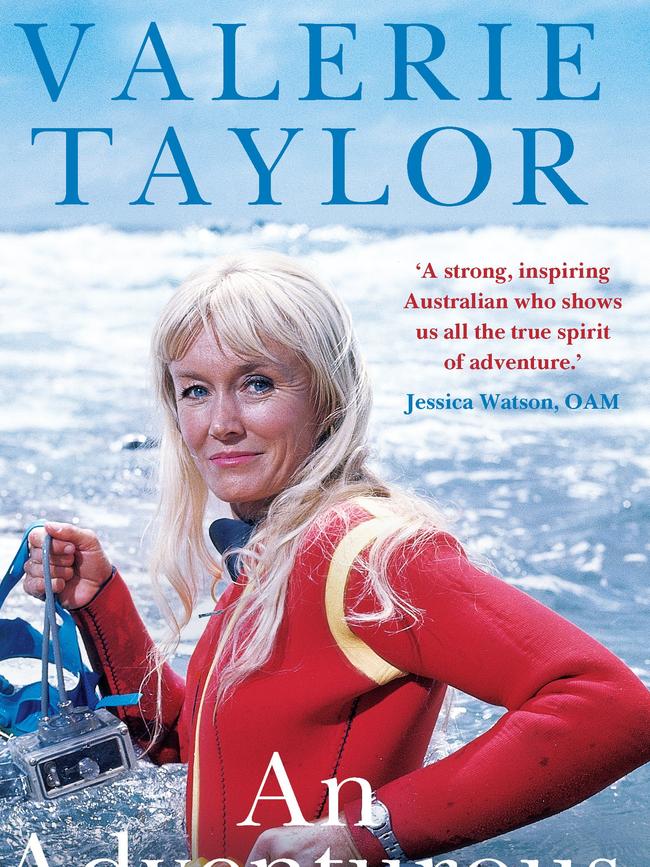

Taylor has recently written An Adventurous Life, with Ben McKelvey, about her experiences on the blue planet and the adventures just keep on coming, despite the onset of arthritis and loss of her beloved husband in 2012.

“I’m still diving,” she says. “It’s very easy to dive, there’s no gravity. I can swim as fast now as I could when I was in my 20s. I can’t run at all and I can hardly walk. Well, I can walk, but I’ve got two artificial knees from the arthritis and one of them doesn’t work so good.”

STANDING ON THE HANDLEBARS

Born in 1935, Taylor grew up in pre-war Australia and later New Zealand, in what she describes as a carefree childhood, despite being struck down by polio in the 1950s.

“We went to New Zealand when I was four,” she says. “During the war my favourite game was goodies and baddies in the street with the other kids. The baddies would always be the Germans... We rode bikes and practised standing on the handlebars and stupid things like that.

“We had a very happy childhood, I really think, except for polio. That pulled me down a lot.”

Millions died in the worldwide epidemic and those who survived were left with paralysed limbs and a long road to recovery. A therapy devised by an Australian bush nurse, known as the “Sister Kenny” treatment, gained recognition before the Salk vaccine was approved in 1955. “It was a series of hotpacks and exercises, very painful and it took a long time,” she says. “They didn’t bother with my arm, so it’s a bit short and my shoulder’s a bit small but my legs are both the same length. A doctor who’d worked in the clinics in America was there. I owe that man – I don’t know who he was – a lot.”

LOVE OF THE WILD

The therapy meant Taylor could take full advantage of the world around her parents’ waterfront home in Sydney. “I always wanted to study animals in the jungle and that was an impossibility – I wasn’t around any jungle,” she says.

“I started spearing fish, free diving. Then I joined a club ... and I met my husband and he was the men’s world spearfishing champion.”

The meeting generated a lifetime partnership and a change of perspective for both young people. “We were at the Australian titles and we looked at all those dead fish and Ron said ‘I’m not going to do this any more’. I said ‘I can’t believe it, look what we’ve done. We’ve taken every edible, decent-size fish off that reef’. We walked away and we never did it again.”

HOLLYWOOD HYPE

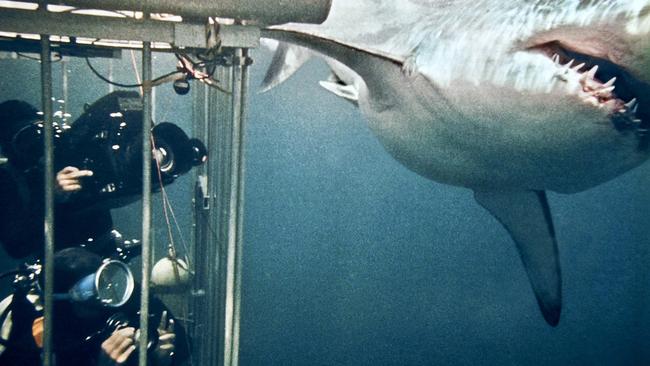

“My husband wanted to be an underwater cinematographer and he became an underwater cinematographer,” Taylor says. “We worked together very closely. I did all the still photography and sometimes I used the movie camera and I got some very good sequences when we were shooting Jaws. My contribution was mainly that I would do anything.”

In the 1960s and ’70s, the pair filmed the Great Barrier Reef from top to toe, starred in full-length documentary Blue Water White Death, and became known for their expertise filming sharks.

When Richard Zanuck and David Brown came knocking asking for their help with the shark sequences in Jaws, the couple readily agreed. Presented with a list of shark scenes needed: “Ron said we’d have to be out there for over a year to get all these shots – you can’t tell a shark what to do. You’ve just got to wait and hope it does something like what’s written here. And that’s when they decided to get the artificial shark. But every time you see a whole shark, it’s an Australian shark filmed by Ron 100 per cent.”

The scenes, filmed off South Australia, are now iconic in a movie that took the world by storm in 1975. But few expected the audience reaction to the film, which entrench all sharks as public enemy No.1.

“The pendulum swung too far,” Taylor says. “It’s a fictitious story about a fictitious shark. Universal took us to America and we did every talk show in the States telling people not to be afraid. It didn’t seem to make a lot of difference.

“Gung-ho guys seemed to want to go and kill sharks and ... it’d be a poor old grey nurse that wouldn’t hurt anyone. It just sickened us.”

Many more Hollywood movies followed until the physical strain of filming meant it was time to wind back on their projects.

KICKING BACK (SORT OF)

Semi-retirement meant the couple still spent plenty of time in the water, they were just more choosy about where and when. “We did a lot of documentaries, some of our own and some for other people,” Taylor says. “That was a lot more fun.”

Their tremendous knowledge of the marine world meant they could rally to conservationist causes, while sharing their knowledge with the world. There work was recognised in many quarters, including the renaming of a South Australian landmark to Neptune Islands Group (Ron and Valerie Taylor) Marine Park, home to many of great white sharks.

Diagnosed with myeloid leukaemia, Ron died in 2012. Picking up the pieces has been tough for Valerie. “You don’t get over it – I don’t,” she says. “Even just the small things. This morning opening a bottle of milk. Ron used to open the milk.

“When I’m doing something good in the water, now, I wish he was watching. He’d probably be telling me I’m doing it all wrong.”

AN 80S THING

“I still work. I don’t think anything is crucial anymore but I wake up in the morning and I write down what I’m going to do,” Taylor explains. “Wash the clothes, buy some food, it goes through everything. … spend three hours drawing and two hours on the computer on a story.

“I very rarely get through everything but I have a feeling people my age need a plan when they wake up. That keeps you motivated and on the go. My downfall is good books.”

She also shares her large house with an overseas student who helps out with household tasks: “I’m used to having another person in the house.”

Keeping up with the demands of an admiring public is sometimes difficult but her passions remain centre focus. “On Wednesday, I’m going to a place up north called Seal Rocks where I have a little house with a film crew to do a sequence for a film that’s being made,” Taylor says. This month, she’s off to dive Milne Bay in Papua New Guinea.

“An Adventurous Life” is available in bookstores and online

WHY I LOVE SOUTH AUSTRALIA

“Whatever you write, give your own state a bit of a plug,” says Valerie Taylor, who has good reason to love South Australia, where key scenes of Jaws were filmed.

“SA has the best all-round diving in the world. You have everything and over 80 per cent of your marine life is endemic – it’s found nowhere else in the world. Your white sharks are different, I can assure you. You don’t need a cage swimming with white sharks off Mexico. You wouldn’t dare not have a cage in SA.

“And the jetties are a marvel, a miracle to dive, brilliant. There’s the giant cuttlefish and if it’s bad weather you can go to the sinkholes. If you don’t want to dive, go to the wineries.

“SA is like the crown jewel. It’s got a little bit of everything good.”