History’s most unusual Christmas presents

From a barbed wire harp to an elephant, these are some of the gifts you won’t find under the tree this week.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Ancient history behind Sydney’s ‘epic’ Coliseum theatre

- Rebel cricketer told officer to ‘Get stuffed’

ON THIS DAY: DECEMBER 23

If you are still looking for the perfect Christmas gift but think items such as socks, shortbread biscuits or a bottle of scotch are a bit run-of-the mill, then you only need to turn to history to find some great gift ideas. Some may not be practical, some were a bit strange but they shows that some of our forebears were thinking outside the box when they decided to embrace the seasonal spirit of giving.

How about a giant Christmas tree? If you have ever been in London’s Trafalgar Square in the weeks before Christmas you might have noticed a Christmas tree dominating the public space. At about 20m tall and weighing about four tonnes, it is not your average tree, but a gift from Norway to England that has been given every year since 1947. The tradition owes its origins to Britain’s support of Norway during World War II.

Despite stating an intention to remain neutral, Norway was invaded by Germany in April 1940. Norway’s King Haakon VII and his government were offered refuge in the UK, and the British helped organise resistance efforts. As a thank you, after the war, the king initiated the practice of sending a huge tree as a reminder of Britain’s assistance.

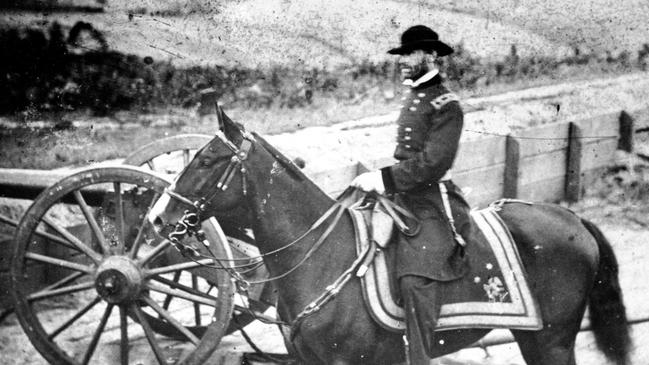

ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S GIFTED CITY

Few could ever have afforded to give someone an entire city for Christmas but just before Christmas in 1864 Union General William T. Sherman captured the city of Savannah in Georgia. He sent a telegram to US president Abraham Lincoln “I beg to present you, as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.”

The president wrote back “Many, many thanks for your Christmas gift, the capture of Savannah.” He went on to say he had been “anxious if not fearful” about Sherman’s military expedition, from Atlanta Georgia to Savannah on the Atlantic Ocean, but “feeling that you were the better judge and remembering that ‘nothing risked nothing gained,’ I did not interfere. Now the undertaking being a success, the honour is yours.”

Relations between the two men had previously been tense but this gift helped ease those tensions. Sherman wrote to Ulysses Grant, the commander of the Union army, “Please say to the President that I received his kind message through Colonel Markland, and feel thankful for his high favour. If I disappoint him in the future, it shall not be from want of zeal or love to the cause.”

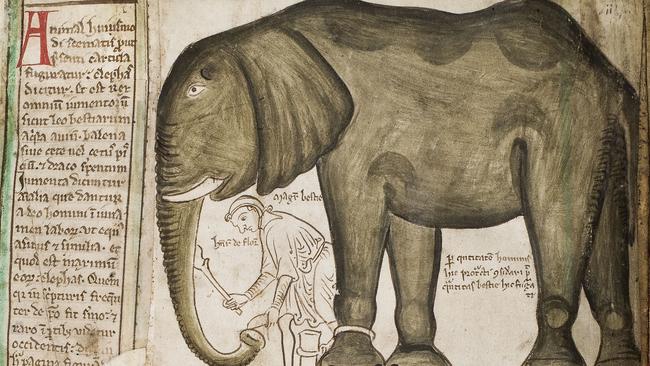

LOUIS IX’S ELEPHANT

If a city is too much perhaps something smaller like an elephant would fit the bill.

In 1255 French King Louis IX sent a pachyderm as a gift to Henry III of England. Louis had been on the somewhat disastrous seventh crusade in Egypt, where his army had been defeated by the Mameluk forces and he had been captured and nearly died of dysentery, before being ransomed. But his armies had captured the elephant.

The creature was delivered to its new captor at Michaelmas (September) to the Kentish coast and was then walked along the Canterbury to London road, before being rowed into the city of London by boat to be delivered to the Tower of London, where the king housed a growing menagerie of exotic beasts also given as gifts. The Sheriffs of London paid to have a large wooden elephant house built, but the poor animal died after only two years.

The 189.62 carat gem gifted by Count Orlov to his former lover Catherine the Great, the empress of Russia, in 1774, was the elephant of the diamond world.

Orlov had fallen out of favour with Catherine and was trying desperately to win back her affections by giving her the massive diamond, said to have been stolen from India. His gift did not work, Catherine refused to be reconciled, kept the diamond and had it mounted in an imperial sceptre.

But historians believe Orlov could never have had enough money to acquire the diamond and that Catherine invented the story about it being a Christmas gift to deflect criticism for her excesses. However, the priceless diamond, still bears Orlov’s name.

DALI’S BARBED WIRE HARP

Spanish surrealist artist Salvador Dali gave his friend, the American harp-playing comedian Harpo Marx, a most unusual gift.

Dali was a huge fan of the Marx Brothers films, for their often surreal sense of humour and when he met Harpo at a party in Paris they hit it off straight away. In 1936 he sent a Christmas gift of a large harp with barbed wire for strings and spoons for tuning knobs.

Harpo sent back a photograph of himself with bandaged fingers.

The pair later got together to mug for the camera with Dali sketching Harpo as he played his unplayable harp artwork.

ON THIS DAY: DECEMBER 21, 1920

It was going to be a great day for cricketer Dr Claude Tozer. He opened the paper on the morning of December 21, 1920, to read he had been chosen as captain of the NSW team to play Queensland. Selectors had previously hinted to him that if he played well enough he might be chosen for to play for Australia in the 1920-21 Ashes series.

But first he had some personal business to clear up. The day prior he had visited Dorothy Mort, a former patient with whom he had been having an affair, to tell her he had proposed to another woman and needed to end the relationship with Mort. Although obviously stunned by the news, Mort seemed calm and asked him to return the next day so that she could say a proper farewell.

He went to her home on December 21 and was shown to Mort’s bedroom by her maid, Florence Fizelle. The door closed behind them. Ten minutes later, at about 11.30am, gunshots rang out. Fizelle went to the door to check on her employer, but was assured everything was all right.

When Mort failed to emerge, Fizelle tried for hours to convince her boss to open the door. At 7pm she finally forced it open to find Tozer dead from gunshots to the head and chest and Mort drugged and covered in blood.

The crime gripped Australia before Christmas 1920 as it marvelled at the brutal death of the doctor, war hero and promising cricketer, murdered by a married patient with whom he had been conducting a clandestine romance.

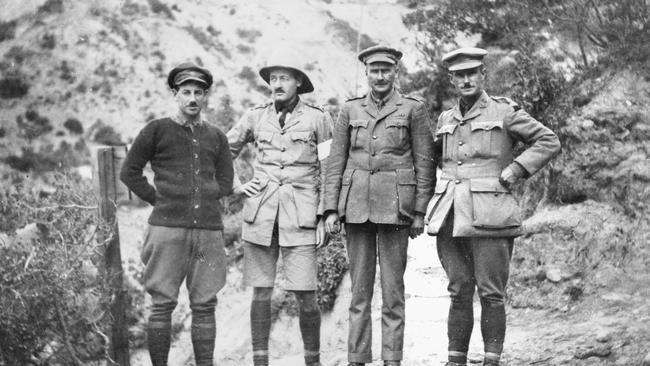

GALLIPOLI SERVICE

Tozer was born in 1890, the son of a bank manager Jonathan Tozer and Beatrice (nee Charlton) sister of Percie Charlton, an Australian Test cricketer, and aunt of Andrew “Boy” Charlton, the great swimmer.

Tozer’s father was also passionate about cricket and encouraged his son when he took to the game at the exclusive boy’s school Shore in North Sydney, becoming their star batsman. Also a brilliant student, winning prizes in literature, mathematics, Latin and history, he went on to University of Sydney, where he also shone at the sport, making his first class debut playing for NSW against South Africa in 1911.

He graduated with a medical degree in 1914 and had started his residency when war was declared in August of that year. After troops had landed at Gallipoli in April 1915 and a call

went out for more medical help at the front, Tozer signed up in May 1915 and left aboard the hospital ship Karoola in June.

He was assigned to a hospital in Egypt but was soon ordered to Suvla Bay, Gallipoli. It was not long before he had his first brush with death, albeit a false one. Shortly after his arrival a rumour reached Sydney he had been killed. Flags were flown at half mast at the Sydney Cricket Ground and cricketers donned black armbands. An orderly later sent a letter to Sydney telling them that Tozer was alive and well.

He was later posted to a hospital on Lemnos, as Regimental Medical Officer to the 12th Infantry Battalion. But in February 1916 he contracted typhoid, came close to dying, and was sent back to Egypt to recover.

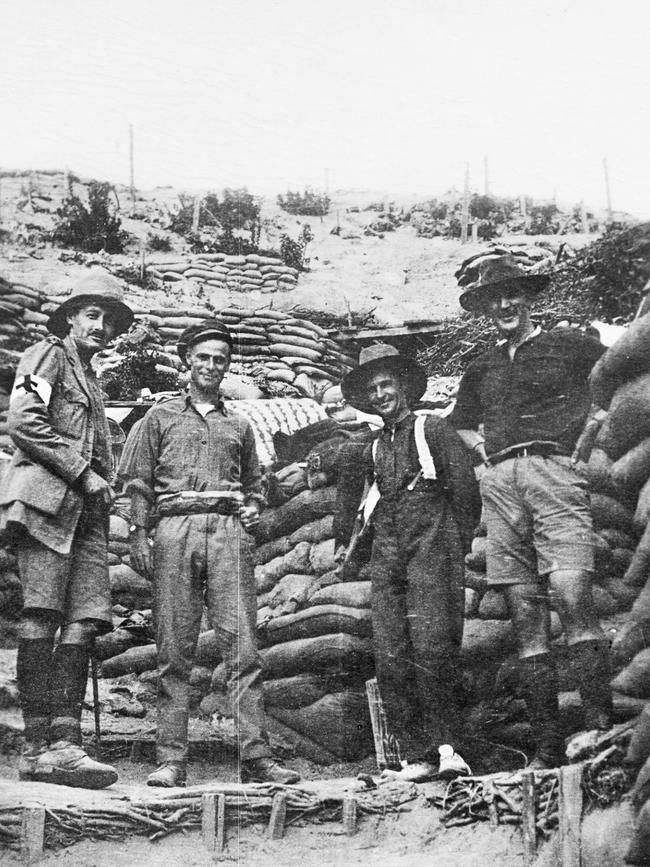

In March he rejoined the 12th as they headed to France and in July 1916 at Pozieres was injured by shrapnel from a bomb exploding near him. A piece of the shrapnel lodged under his skull but it was too dangerous to operate to remove it. Tozer spent 12 weeks recuperating in England and to make matters worse he also contracted trench fever.

He returned to France and in 1917, had another bout of trench fever and earnt promotion to major. In Belgium at Hooge Tunnel, near Ypres, in October 1917 he showed “conspicuous courage and devotion to duty dressing wounded in the open under fire.” He was awarded a Distinguished Service Order. Posted to the Australian Hospital in Abbeville where he treated wounded from the battles raging in the Somme, he had time to indulge in the occasional cricket match.

He returned to Australia in December 1918, but suffered shell shock and from headaches caused by the shrapnel lodged in his head. To try to give his life some focus he opened a medical practice on the North Shore.

He also made plans to marry his fiancee Kathleen Crossman, but at the end of May 1919 she suddenly took ill, with vomiting, hot spells, sore tonsils and lethargy. She died in June.

Tozer buried himself in his work and went back to playing cricket.

AFFAIR WITH DOROTHY MORT

In June 1920 engineer Harold Mort, a member of the wealthy Mort family of Goldsborough and Mort Ltd fame, brought his wife Dorothy to Tozer for treatment for depression. There was a history of mental illness in Dorothy’s family, her father had nearly killed her mother and brother with an axe handle and he later killed himself.

Dorothy quickly fell for Tozer, flirting with him. He resisted but eventually returned the attention. But later that year as his cricket career looked like taking off, with selectors telling him that he might be chosen to play for Australia, he decided that if it got out that he was seeing a married woman it could damage his chances.

After he told Mort he wanted to put and end to their affair she went to a jeweller to sell a diamond brooch to get money to buy a gun.

She also bought a bottle of laudanum, an opium mixture used to treat a range of ailments. The next day, when Tozer arrived, she handed him a photograph of herself. On the back was written: “From the woman you swore you loved above all other, and said was the biggest incentive for good in your life. From the woman you swore you said you loved and had made the mother of your child.”

It failed to convince him not to break off their relationship so Mort shot him three times, then tried to shoot herself. When that failed she tried to overdose on laudanum.

This time there was a genuine reason for lowering the flags and wearing black armbands at the SCG.

Mort was acquitted due to insanity, but was locked up in Long Bay Gaol at the Governor’s pleasure. Through the efforts of her husband she was released in 1929 and died in 1966.

Acknowledgments to Cricketers At War by Greg Growden, ABC Books, $32.99

Originally published as History’s most unusual Christmas presents