Tasmania Thylacine genome breakthrough brings de-extinction closer

The race to bring the Tasmanian tiger back to life is heating up after a scientific breakthrough has completed 99.9 per cent of the puzzle. Here’s why.

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A US bioscience company that is racing to bring the Thylacine back from extinction has announced a suite of key milestones in the controversial project, including producing the most complete genome of any ancient species to date.

Established in 2021 with the intention of re-birthing the Thylacine within a decade, Colossal say they have “smashed” major landmarks in that quest, including constructing the world-first Thylacine genome that is 99.9 per cent accurate – making it the most complete genome ever constructed of an ancient animal.

The team has been aided by using samples from a thylacine head that was skinned and preserved in ethanol, as well as dozens of thylacine pelts with genetic diversity.

Among the many reasons the Thylacine was chosen for de-extinction was because of how recently it lived – with the last recorded animal dying in Hobart in 1936.

“I feel like it’s one of those animals that is just out of living memory, you know?” says co-founder of Colossal, Ben Lamm.

Colossal scientists have also managed to isolate the regions of individual genomes that give the Thylacine its distinctive jaw and skull; similar to those seen in some wolves and dogs.

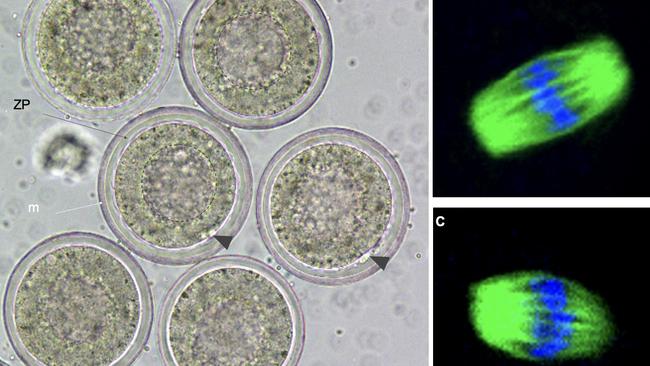

They have used this discovery to gene-edit the cell line of fat-tailed dunnart, a mouse-like marsupial, which may eventually carry the world’s first thylacine embryo.

The fat-tailed dunnart has been chosen because it breeds well in captivity, and is an ideal surrogate to host the Thylacine embryo, scientists say.

Because of the gene edits to the dunnart line being used to re-create the Thylacine, the final animal will technically be a “hybrid” creature.

The recent edits of the dunnart cell line make it the most edited animal cell on record – with over 300 unique genetic changes edited into its genome.

Changes that could one day lead to the world’s first ever de-extinct animal.

Rewilding in Tasmania

Colossal was established in 2021 by a Harvard geneticist and a serial entrepreneur with the goal of bringing the Tasmanian tiger, the Woolly Mammoth and the Dodo back from extinction.

The long-game is to reintroduce the animals to their original wild habitats to restore the delicate balance of the ecosystem – which in Tasmania means welcoming a genetically engineered hybrid apex predator into the modern world.

“I think it’s really important to investigate what the opportunities [of this technology] are,” says Greg Irons, the Director of Bonorong Wildlife Park and a member of Colossal’s Tasmanian Advisory Board.

“I think it’s too early to say if it’s the right thing to do or the wrong thing to do. When there are currently no animal welfare or ecological concerns, I think it would be remiss of us to ignore this incredible opportunity.”

Unsurprisingly, sceptics of Colossal’s work are plentiful and loud, especially on the internet, where memes of Jurassic Park run hot.

But Mr Lamm is unperturbed.

“The Thylacine was so critical in maintaining the balance in Tasmania that we have to do this now if we want to save those environments,” he says.

“We always like to play God; who stopped to pause when we wiped the thylacine off the face of the planet? So at least now with these technologies we can start to correct some of those wrongs.”

Mr Irons from Bonorong agrees. “It’s us who did the damage. We have to take some responsibility to try and fix what we’ve done.”

Professor Barry Brook is Head of Biological Sciences at the University of Tasmania and a Professor of Environmental Sustainability.

He is broadly supportive of the work Colossal is undertaking and says he would like to see Thylacines reintroduced – in a carefully managed way – to Tasmania. He believes the scientific probability of the animals coming back is now “possible, it could occur.”

“They’ve been gone 80 years, which in ecological terms is a flash of a disappearance,” Prof Brook said, adding that he doesn’t believe Colossal are “playing god” because humans have always imposed themselves on the natural world – for gain and for good.

“ I can imagine that ecologically the Thylacine would fit in very nicely if they came back.”

Straight out of science fiction

Dr Andrew Pask is the head of the Thylacine Integrated Genomic Restoration Research Laboratory at the School of Biosciences in The University of Melbourne. He is also on the Collosal Advisory board.

Dr Pask admits the whole project may sound weird, and “like something out of science fiction”, but he believes the science is robust and important.

“There’s no question it’s the right thing to do,” he said.

“Nobody has done this anywhere in the world, so we’re pushing boundaries and that can scare people. But these are absolutely critically needed technologies to save biodiversity.”

The Derwent Valley is the scene of the last wild sighting of the Tasmanian tiger.

Derwent Valley mayor Michelle Dracoulis sits on Colossal’s Tasmanian Advisory Council.

She says she has approached her role “very critically”.

“My concerns are not about the science,” she says.

“I have concerns about what the community response will be and the safety of these animals once they’re back in the world. I also have concerns that people will think we can just “fix” extinction now so saving animals doesn’t matter.”

But like Professor Brook, the opportunities of the de-extinction project excite Ms Dracoulis, whose motivation for being involved is simple; saving the land and the state she loves.

Mr Lamm says humans are “always” scared of innovative or new technologies – such as vaccines. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t “thoughtfully” explore them.

“The truth is that we, our planet, is in the middle of this sixth mass extinction. We’ve already lost species that were absolutely critical for maintaining certain environments. I don’t want to see that happen ever again.”

eleanor.dejong@news.com.au

More Coverage

Originally published as Tasmania Thylacine genome breakthrough brings de-extinction closer